Henri Bergson (1859-1941) From “The Perception of Change” (1911

advertisement

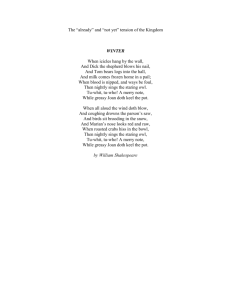

Henri Bergson (1859-1941) From “The Perception of Change” (1911), in Key Writings: “We say that change exists, that everything changes, that change is the very law of things: yes, we say it and we repeat it; but those are only words, and we reason and philosophise as though change did not exist.” (249) From Creative Evolution (1907 – from the modern Dover reprint): “Thus, it will be said that the function of intellect is essentially unification, that the common object of all its operations is to introduce a certain unity into the diversity of phenomena, and so forth.” (152) “Just as we separate in space, we fix in time. The intellect is not made to think evolution, in the proper sense of the word—that is to say, the continuity of a change that is pure mobility …. Intellect represents becoming as a series of states, each of which is homogenous with itself and consequently does not change.” (163) “Here again, thinking consists in reconstituting, and, naturally, it is with given elements, and consequently with stable elements, that we reconstitute. So that, though we may do our best to imitate the mobility of becoming by an addition that is ever going on, becoming itself slips through our fingers just when we think we are holding it tight.” (163) “Precisely because it is always trying to reconstitute, and to reconstitute with what is given, the intellect lets what is new in each moment escape. It does not admit the unforeseeable. It rejects all creation.” (163) “[T]he natural obstinacy with which we treat all the living like the lifeless and think all reality, however fluid, under the form of the sharply defined solid. We are at ease only in the discontinuous, in the immobile, in the dead. The intellect is characterized by a natural inability to comprehend life.” (165) “It [i.e., the idea that phenomena exist as discrete entities, rather than as events], is natural to our intellect, whose function is essentially practical, made to present to us things and states rather than changes and acts. But things and states are only views, taken by our mind, of becoming. There are no things, there are only actions.” (248) First Gentleman: I make a broken delivery of the business, but the changes I perceived in the King and Camillo were very notes of admiration. They seemed almost, with staring on one another, to tear the cases of their eyes. There was speech in their dumbness, language in their very gesture. They looked as they had heard of a world ransomed, or one destroyed. A notable passion of wonder appeared in them, but the wisest beholder, that knew no more but seeing, could not say if th’importance were joy or sorrow. But in the extremity of the one, it must needs be. The Winter’s Tale 5.2.8-17 Third Gentleman: [….] Did you see the meeting of the two kings? Second Gentleman: No. Third Gentleman: Then you have lost a sight which was to be seen, cannot be spoken of. There might you have beheld one joy crown another, so and in such manner that it seemed sorrow wept to take leave of them, for their joy waded in tears. There was casting up of eyes, holding up of hands, with countenance of such distraction that they were to be known by garment, not by favour. Our king being ready to leap out of himself for joy of his found daughter, as if that joy were now become a loss cries, ‘O, thy mother, thy mother!’, then asks Bohemia for forgiveness, then embraces his son-in-law, then again worries he his daughter with clipping her. Now he thanks the old shepherd, which stands by like a weather-bitten conduit of many kings’ reigns. I never heard of such another encounter, which lames report to follow it, and undoes description to do it. The Winter’s Tale 5.2.36-52 Winter [sings]: When icicles hang by the wall, And Dick the shepherd blows his nail, And Tom bears logs into the hall, And milk comes frozen home in pail; When blood is nipped, and ways be foul, Then nightly sings the staring owl: Tu-whit, tu-whoo!—a merry note, While greasy Joan doth keel the pot. When all aloud the wind doth blow, And coughing drowns the parson’s saw, And birds sit brooding in the snow, And Marian’s nose looks red and raw; When roasted crabs hiss in the bowl, Then nightly sings the staring owl: Tu-whit, to-whoo!—a merry note, While greasy Joan doth keel the pot. Armado: The words of Mercury are harsh after the songs of Apollo. You that way, we this way. Love’s Labour’s Lost 5.2.887-904