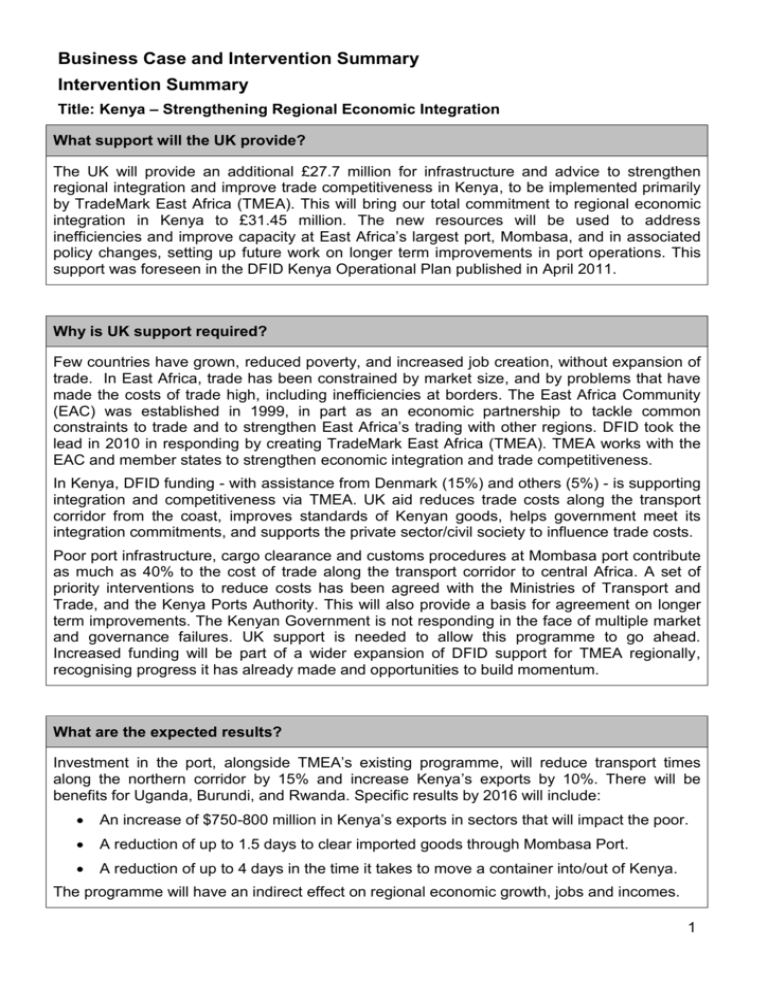

What support will the UK provide? - Department for International

advertisement