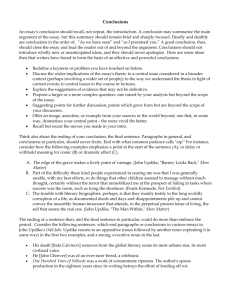

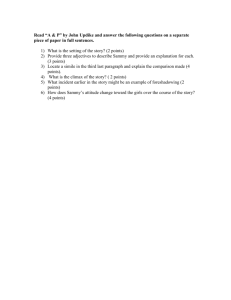

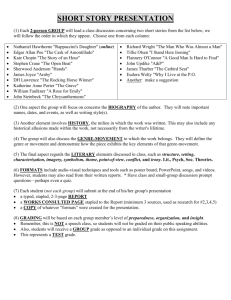

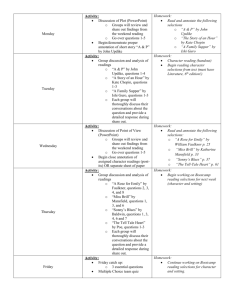

chapter_2

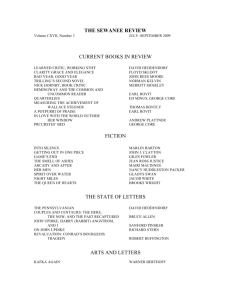

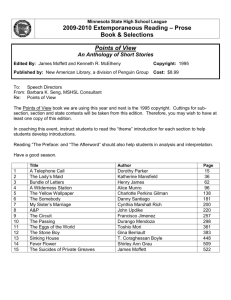

advertisement