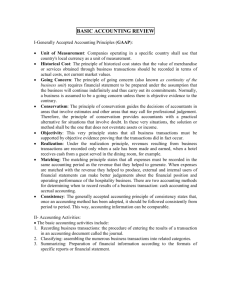

Welker - PB Conservatism

advertisement

The Link Between Earnings Conservatism and Balance Sheet Conservatism Jinhan Pae Dan Thornton Mike Welker Queen’s University 1 The Punch Line: Basu documents that earnings are much more highly correlated with bad news (negative stock returns) than with good news (positive stock returns) We argue that earnings conservatism is related to the conservatism in the balance sheet at the beginning of the period (most straight forward way to see – lower of cost or market rules - suggest that recognition of bad news is a function of the relation between book and market, recognition of good news is not) We use market to book to measure balance sheet conservatism and document a very strong negative relation between market to book and earnings conservatism We further document that this relation is principally driven by 2 the accrual component of earnings Earnings Conservatism Inherent in accounting standards – Expense R&D and advertising – Recognize post-retirement obligations but not human assets – Write down impaired goodwill but don’t recognize internally generated goodwill. SEC enforcement augments or diminishes it – e.g., SAB 101’s strict revenue recognition criteria. 3 Empirical literature to date operationalizes conservatism and explains its “existence” Watts’ (2003) –: “Differential verifiability required for recognizing profits versus losses.” Earnings conservatism measure: Degree to which a firm’s accounting income reflects expected losses in a more timely fashion than expected gains (Basu 1997). 4 Simple empirical measure of the timeliness of accounting numbers X it 0t 1t Rit it Cross sectional regression coefficient 1t measures the timeliness with which accounting numbers reflect returns Xit : firm i’s earnings, accruals, or operating cash flows for fiscal year t, deflated by the market value of equity at the end of year t–1. Rit : the market rate of return on firm i’s common stock for the year ending 3 months after fiscal year t it : assumed to be noise. 5 X it 0t 1t Rit it Good news firms (R 0): Estimate 1tGN Bad news firms (R < 0): Estimate 1tBN General approach – Estimate 1tGN (1tBN) in year t for samples of firms reporting good (bad) news – Cross sectional regression at t or pooled. We define conservatism as ct ≡ 1tBN - 1tGN – Excess sensitivity of earnings to bad versus good news for fiscal year t. 6 We are interested in “responsiveness” Unaddressed so far in empirical literature Does earnings conservatism increase with managers’ incentive to overstate earnings/net assets? We hypothesize that this incentive, and hence earnings conservatism is negatively associated with balance sheet conservatism. – Balance sheet conservatism measure: lagged market-to-book ratio Pt-1/Bt-1 – Proxy for changes in expected gains or losses: stock returns (Basu, 1997). • Assumes market efficiently reflects investor perceptions 7 Summary of Approach X it 0t 1t Rit it Conservatism ct ≡ 1tBN - 1tGN Good news firms (R 0): Estimate 1tGN Bad news firms (R < 0): Estimate 1tBN – Earnings Conservatism at t is the excess sensitivity of earnings to bad versus good news for fiscal year t. We hypothesize ct is negatively associated with balance sheet conservatism, Pt-1/Bt-1 – Pt-1 (Bt-1) represents the market (book) value of equity at the end of fiscal year t–1. – (For brevity we call this “the P/B ratio”). 8 Three hypotheses in alternate form H1a: Existence: ct > 0 for all t. That is, earnings are conservative in all periods examined. H2a: Responsiveness: With earnings as the dependent variable, ct is negatively associated with Pt-1/Bt-1. H3a: Responsiveness: With accruals as the dependent variable, ct is negatively associated with Pt-1/Bt-1. 9 Fourth hypothesis in null form H40: With operating cash flows as the dependent variable, ct is independent of Pt-1/Bt-1. That is, cash flow conservatism is not associated with balance sheet conservatism. – Accountants don’t control this (except, maybe, to urge selling off assets for cash). 10 Hypotheses development • Review Watts’ (2003) four explanations for existence of conservatism 1. Contracting 2. Shareholder litigation 3. Regulation 4. Taxes • Extend each explanation to derive our hypothesized negative association between earnings conservatism and balance sheet conservatism. 11 Contracting Explanation for Conservatism Accounting measures are common in contracts constraining managers in expending resources and splitting returns among firm claimants (Holthausen and Leftwich, 1983; Watts and Zimmerman, 1986). 12 Contracting I: Management compensation agreements Existence of Conservatism – Managers with limited tenure have incentives to inflate earnings to increase their bonus compensation and increase the value of their stock options. – Earnings conservatism facilitates delivered performance measurement (Barclay et al. 2000) by deferring the recognition of gains until they are verifiable. 13 Contracting I: Management compensation agreements Negative P/B Association – Decrease in P/B signals a decline in a firm’s future growth opportunities, increasing managers’ preference for current vs. deferred compensation. – Motivates managers to overstate current earnings to increase bonus, stock option compensation. 14 Contracting II: Debt contracts Existence of Conservatism – Debt covenants restrict firm from making unrecoverable payments to shareholders and junior claimants (Leftwich, 1983). • Recipients of excessive dividend payments do not generally need to return them to the firm in the event of financial trouble. – Limit dividend payments to “unrestricted” retained earnings. – Restrict additional borrowing by placing upper limits on firms’ debt/equity ratios. – Corporations laws say “dividend distributions neither make a company insolvent nor impair its capital.” 15 Contracting II: Debt contracts Negative P/B Association – Earnings Constraints – As P/B decreases, the probability of default increases because the value of the firm’s expected future cash flows (numerator) decreases vis a vis principal amount of debt. – Following a decrease in P/B, debt holders wish to tighten constraints on excessive payouts and additional borrowing. – The contractual constraints protecting debt holders against excessive payouts generally refer to earnings (often before interest and taxes) based on GAAP, not market-based earnings measures. – Earnings conservatism directly constrains dividend and compensation payouts based on earnings. 16 Contracting II: Debt contracts Negative P/B Association – Debt/Equity Constraints – Constraints protecting debt holders against excessive additional borrowing generally refer to a maximum D/E based on book value equity measure. – Earnings conservatism triggers impaired asset write-offs and recognition of unrecorded liabilities in the income statement, pushing the D/E closer to its maximum limit and tightening the constraint on additional borrowing. – Debt holders to rely on earnings conservatism increasing as P/B decreases, more than offsetting managers’ increasing incentives to overstate earnings, overstate assets, and understate liabilities. 17 Hypotheses development • Review Watts’ (2003) four explanations for existence of conservatism 1. Contracting 2. Shareholder litigation 3. Regulation 4. Taxes • Extend each explanation to derive our hypothesized negative association between earnings conservatism and balance sheet conservatism. 18 Shareholder litigation Existence of Conservatism – Earnings conservatism reduces the expected present value of shareholder litigation costs – Shareholders are much more likely to litigate when earnings and net assets are overstated than when they are understated Watts (1993, 2003), Kothari et al. (1988), and Beaver (1993). 19 Shareholder litigation Negative P/B Association – As P/B decreases • It becomes more likely that net asset carrying values exceed fair values. • Probability of shareholder litigation increases because shareholders can more readily substantiate claims that assets are misleadingly overvalued. • Likely magnitude of claimed damages increases as investors can claim that asset carrying values are farther below fair values. – Hence, to reduce expected litigation costs, it is efficient for both auditors and managers to increase the degree of earnings conservatism as P/B decreases. 20 Hypotheses development • Review Watts’ (2003) four explanations for existence of conservatism 1. Contracting 2. Shareholder litigation 3. Regulation 4. Taxes • Extend each explanation to derive our hypothesized negative association between earnings conservatism and balance sheet conservatism. 21 Regulation Existence of Conservatism – Investor losses from overvalued assets and overstated earnings are more observable and usable in the political process than forgone gains due to undervalued assets or understated earnings (Watts 1977, Benston 1969). – Thus, standard-setters have incentives to set conservatively worded GAAP; regulators like the SEC have incentives to enforce GAAP in a conservative fashion. 22 Regulation Negative P/B Association – Low P/B ratios imply poor future prospects for companies and are consistent with recent declines in values having occurred, making it likely that investors will blame regulators for permitting misleading accounting practices. – Thus, both the wording and required implementation of many accounting standards imply a negative association between earnings conservatism and the P/B ratio. Examples: • Inventory at the lower of cost or market. • SFAS 142 mandated goodwill impairment write-downs • SFAS 5 contingent loss recognition 23 Hypotheses development • Review Watts’ (2003) four explanations for existence of conservatism 1. Contracting 2. Shareholder litigation 3. Regulation 4. Taxes • Extend each explanation to derive our hypothesized negative association between earnings conservatism and balance sheet conservatism. 24 Taxes Existence of Conservatism – Incentives for profitable firms with taxable income to defer income (be conservative) to reduce the present value of taxes (Watts, 2003; Smith and Watts, 1982; Watts and Zimmerman, 1979; Guenther et al. 1997; Shackelford and Shevlin 2001) 25 Taxes Negative P/B Association?? Managers’ incentives – Increase reported income to increase bonuses – Decrease reported income to save corporate taxes It is unclear (to us) how declines in P/B affect the tradeoff. So, we limit our analysis of the implications of Watts’ (2003) conservatism explanations to contracting, litigation, and regulation. 26 Results 27 Mean Standard Deviation First Quartile Median Third Quartile Min Max R 0.12 0.58 -0.23 0.04 0.34 -0.97 8.39 NI 0.03 0.20 -0.01 0.06 0.11 -2.46 0.98 ACC -0.09 0.23 -0.14 -0.04 0.01 -3.61 1.17 OCF 0.11 0.23 0.00 0.09 0.20 -1.25 3.34 MV 1,114.29 7,322.57 16.92 69.47 358.05 0.06 467,096 Sales 1,045.27 4,917.51 25.35 104.07 447.47 -203.75 217,799 P/B 3.82 60.65 0.96 1.61 2.90 0.03 10,474 Mean Standard Deviation First Quartile Median Third Quartile Min Max R 0.47 0.56 0.14 0.31 0.61 0.00 8.39 NI 0.07 0.17 0.04 0.08 0.14 -2.36 0.98 ACC -0.09 0.23 -0.14 -0.05 0.01 -3.22 1.17 OCF 0.16 0.24 0.04 0.13 0.24 -1.11 3.34 MV 1,417.60 8,338.03 25.68 108.49 542.50 0.06 467,096 Sales 1,265.43 5,440.95 36.05 139.89 595.05 -4.39 217,799 P/B 3.26 66.71 0.89 1.45 2.53 0.03 10,474 Mean Standard Deviation First Quartile Median Third Quartile Min Max R -0.30 0.22 -0.44 -0.26 -0.12 -0.97 0.00 NI -0.03 0.21 -0.07 0.03 0.07 -2.46 0.90 ACC -0.09 0.24 -0.13 -0.04 0.01 -3.61 1.07 OCF 0.06 0.20 -0.03 0.05 0.14 -1.25 2.83 MV 755.17 5,878.21 11.38 42.03 196.37 0.07 422,640 Sales 784.61 4,199.74 17.19 72.28 303.65 -203.75 195,805 P/B 4.49 52.58 1.06 1.83 3.39 0.03 28 6,620 Variable DATA – TABLE 1 Panel A: Full Sample – 119,983 observations Variable Panel B: Good News (non-negative returns) – 65,044 observations Variable Panel C: Bad News (negative returns) – 54,939 observations Panel A: Full Sample (119,983 observations) Variable R NI OCF R 0.220 0.189 (<0.01) (<0.01) 0.411 (<0.01) ACC 0.002 (0.54) MV 0.029 (<0.01) Sales 0.009 (<0.01) P/B -0.008 (<0.01) 0.447 (<0.01) 0.019 (<0.01) 0.040 (<0.01) -0.010 (<0.01) -0.632 (<0.01) -0.001 (0.68) 0.045 (<0.01) -0.021 (<0.01) 0.018 (<0.01) -0.010 (<0.01) 0.012 (<0.01) 0.624 (<0.01) 0.005 (0.06) NI 0.398 (<0.01) OCF 0.298 (<0.01) 0.523 (<0.01) ACC -0.021 (<0.01) 0.176 (<0.01) -0.616 (<0.01) MV 0.208 (<0.01) 0.141 (<0.01) 0.137 (<0.01) 0.036 (<0.01) Sales 0.148 (<0.01) 0.288 (<0.01) 0.326 (<0.01) -0.086 (<0.01) 0.796 (<0.01) P/B -0.160 (<0.01) -0.294 (<0.01) -0.395 (<0.01) 0.293 (<0.01) 0.298 (<0.01) -0.003 (0.27) -0.055 (<0.01) 29 Panel B: Good News (non-negative returns, 65,044 observations) Variable R NI OCF ACC MV R -0.024 0.010 -0.028 -0.012 (<0.01) (0.01) (<0.01) (<0.01) NI 0.089 (<0.01) 0.426 (<0.01) OCF 0.033 (<0.01) 0.503 (<0.01) ACC -0.011 (0.01) 0.074 (<0.01) -0.720 (<0.01) MV -0.054 (<0.01) -0.092 (<0.01) -0.009 (0.03) 0.013 (<0.01) Sales -0.126 (<0.01) 0.138 (<0.01) 0.227 (<0.01) -0.111 (<0.01) 0.813 (<0.01) P/B 0.006 (0.12) -0.384 (<0.01) -0.441 (<0.01) 0.303 (<0.01) 0.390 (<0.01) Sales -0.060 (<0.01) P/B 0.004 (0.29) 0.292 (<0.01) -0.014 (<0.01) 0.006 (0.15) -0.011 (<0.01) -0.741 (<0.01) -0.025 (<0.01) 0.021 (<0.01) -0.017 (<0.01) 0.016 (<0.01) -0.018 (<0.01) 0.010 (0.01) 0.642 (<0.01) 0.005 (0.25) -0.002 (0.55) 0.034 (<0.01) 30 Panel C: Bad News (negative returns, 54,939 observations) Variable R NI OCF ACC R 0.312 0.244 0.077 (<0.01) (<0.01) (<0.01) 0.333 (<0.01) MV 0.049 (<0.01) Sales 0.079 (<0.01) P/B -0.027 (<0.01) 0.618 (<0.01) 0.038 (<0.01) 0.058 (<0.01) -0.004 (0.33) -0.535 (<0.01) 0.016 (<0.01) 0.062 (<0.01) -0.022 (<0.01) 0.020 (<0.01) 0.000 (1.00) 0.015 (<0.01) 0.584 (<0.01) 0.009 (0.04) NI 0.399 (<0.01) OCF 0.307 (<0.01) 0.462 (<0.01) ACC 0.031 (<0.01) 0.349 (<0.01) -0.523 (<0.01) MV 0.231 (<0.01) 0.262 (<0.01) 0.191 (<0.01) 0.082 (<0.01) Sales 0.237 (<0.01) 0.359 (<0.01) 0.368 (<0.01) -0.045 (<0.01) 0.760 (<0.01) P/B -0.215 (<0.01) -0.128 (<0.01) -0.302 (<0.01) 0.279 (<0.01) 0.274 (<0.01) -0.003 (0.43) -0.115 (<0.01) 31 Replication of Previous Results Consistent with H1a 32 H1a: Earnings are conservative in all periods examined (Table 3) BN 1 GN 1 BN 1 GN 1 Reliably, in all 32 periods from 1970 to 2001 Mean = 0.279 (t = 12.5). Coefficient relating earnings to returns when returns are negative is on average around 10 times larger than coefficient relating earnings to returns when returns are non-negative over this period 33 Table 5 Form 5 portfolios based on the beginning-ofyear P/B. P/B < 1 Portfolio I (16,226 firm-years) and II (16,227). P/B 1 Portfolios III through V ( 29,000 firm-years each). 34 H2a: With earnings as the dependent variable, ct is negatively associated with Pt-1/Bt-1. Panel A: Earnings as Dependent Variable Good News (GN) P/B Adj. R2 0 1 I (low) II Mean of Annual regressions (t-value) 0.029 (1.50) 0.081 (7.80) III 0.085 (11.88) IV 0.068 (18.19) V 0.038 (high) (9.58) 1P/B(I) 1P/B(V) 0.062 (4.56) 0.042 (3.80) 0.024 (4.82) 0.019 (2.55) 0.006 (1.04) 0.056 (4.66) 0.023 0.034 0.016 0.029 0.015 Bad News (BN) 0 1 Adj. R2 0.009 (0.44) 0.086 (6.77) 0.090 (11.89) 0.079 (14.87) 0.041 (9.23) 0.604 (10.82) 0.524 (13.11) 0.371 (12.59) 0.252 (15.98) 0.158 (14.12) 0.446 (8.67) 0.127 0.171 0.152 0.132 0.077 1BN 1GN 0.542 (9.87) 0.482 (11.69) 0.347 (11.45) 0.233 (11.82) 0.152 (10.83) 0.390 (7.92) Increase over next highest P/B portfolio 0.060 (1.67) 0.135 (4.85) 0.114 (6.50) 0.081 (5.12) 35 H3a: With accruals as the dependent variable, ct is negatively associated with Pt-1/Bt-1. Table 5 (Panel B) Panel B: Accruals as Dependent Variable Good News (GN) P/B Adj. R2 0 1 I (low) II Mean of Annual regressions (t-value) III IV V (high) 1P/B(I) 1P/B(V) -0.196 (-12.62) -0.103 (-13.00) -0.071 (-11.73) -0.033 (-7.67) -0.018 (-5.83) -0.013 (-1.06) -0.015 (-1.63) 0.003 (0.56) -0.004 (-0.57) 0.005 (1.00) -0.018 (-1.53) 0.000 0.004 0.002 0.006 0.004 Bad News (BN) 0 1 Adj. R2 -0.187 (-10.21) -0.085 (-8.72) -0.046 (-8.36) -0.022 (-4.90) -0.009 (-2.82) 0.348 (5.52) 0.233 (5.46) 0.167 (4.32) 0.077 (4.83) 0.025 (1.86) 0.323 (5.35) 0.033 0.034 0.029 0.013 0.007 1BN 1GN 0.361 (5.53) 0.248 (5.64) 0.164 (4.39) 0.081 (4.45) 0.020 (1.31) 0.341 (5.47) Increase over next highest P/B portfolio 0.113 (2.16) 0.084 (1.80) 0.083 (2.96) 0.061 (3.01) 36 H40: With operating cash flows as the dependent variable, ct is independent of Pt-1/Bt-1. Table 5 (Panel C) Panel C: Operating Cash Flows as Dependent Variable Good News (GN) P/B Adj. R2 0 1 I (low) II Mean of Annual regressions (t-value) III IV V (high) 1P/B(I) 1P/B(V) 0.224 (16.23) 0.184 (24.36) 0.155 (27.92) 0.101 (28.18) 0.056 (13.05) 0.075 (3.68) 0.057 (4.96) 0.021 (3.06) 0.023 (1.92) 0.001 (0.13) 0.074 (3.98) 0.018 0.011 0.005 0.019 0.012 Bad News (BN) 0 1 0.196 0.255 (13.75) (5.20) 0.171 0.292 (22.69) (12.52) 0.136 0.204 (21.64) (6.14) 0.101 0.175 (26.60) (13.68) 0.050 0.133 (10.58) (10.14) 0.122 (2.66) Adj. R2 0.024 0.047 0.054 0.062 0.050 1BN 1GN 0.180 (3.74) 0.235 (8.99) 0.183 (5.38) 0.152 (8.31) 0.132 (7.50) 0.048 (1.04) Increase over next highest P/B portfolio -0.055 (-1.20) 0.052 (1.29) 0.031 (1.17) 0.020 (0.81) 37 Cash Flow vs. Accruals Cash flows: No declines significant Individually or in total 0.600 Earnings Earnings: All declines individually Significant except this one 0.500 Figure 1 Table 5 Accrual component of earnings accounts for 87% of difference in earnings conservatism between the low and high P/B portfolio Conservatism 0.400 Accruals 0.300 0.200 Accruals: All declines individually significant except this one Operating Cash Flows 0.100 Cash flow component of earnings accounts for only 13% of this difference. Market to book less than 1 Market to book greater than 1 0.000 I II III IV V Market to Book Group 38 Conjecture That cash flow conservatism is positive (though unrelated to P/B) is due to firms’ real option to – Adapt assets to next best use (Restructuring charges less persistent than core operating cash flows – Collins et al. 1999) – Liquidate unprofitable operations (Hayn 1995) 39 Table 6 Partitions along two dimensions—the level of accruals and the size of the P/B ratio. Confirms that low-accruals, low-P/B firms exhibit the most earnings conservatism and high-accruals high-P/B firms the least, if any, earnings conservatism. 40 c BN 1 Table 6 Earnings Accruals ACC P/B GN 1 Cash Flows ACC ACC [I, II] [III,IV,V] I, II 0.580 (12.58) 0.234 (8.49) III,IV,V 0.387 (15.56) 0.131 (12.55) P/B I, II III,IV,V P/B I, II III,IV,V I, II 0.331 (8.58) -0.112 (-5.40) I, II 0.249 (8.76) 0.346 (11.57) III,IV,V 0.191 (5.23) -0.048 (-5.10) III,IV,V 0.196 (4.61) 0.179 (17.19) 41 CHANGES IN EARNINGS CONSERVATISM OVER TIME Givoly and Hayn (2000) X it 0 1 Dit 2 Rit 3 Dit Rit it Dit = dummy taking the value 1 (0) when annual stock returns are negative (non-negative). β3 measures EXISTENCE of earnings conservatism. G&H find it has increased over time 42 Our modification X it 0 1 Dit 2 Rit 3 ( D R ) it 4 PBit 5 ( D PB ) it 6 ( PB R ) it 7 ( D PB R ) it it PB = dummy taking the value 1 (0) when P/B is less than (greater than or equal to) one. Thus, – Our 3 is an EXISTENCE measure of conservatism for firms with P/B greater than or equal to one – Our 7 is a measure of RESPONSIVENESS – the extra conservatism exhibited by firms with P/B less than one. 43 Our Results • Table 7 and Figure 2 present the results of estimating pooled regressions using the constant sample of 788 firms that existed throughout our 1970-2001 test period. • β7 increases monotonically from the 1970-75 to the 1991-95 period. • β7 increases more consistently with time than β3 in either G&H or our model. 44 0.700 0.600 Beta Values 0.500 Our 0.400 0.300 GH 3 0.200 Our 0.100 0.000 70-75 76-80 81-85 86-90 Time Period 91-95 962001 45 CHANGES IN EARNINGS CONSERVATISM OVER TIME: Summary • The increase in the negative association between earnings conservatism and P/B is also largely responsible for G&H’s finding that earnings conservatism increased up to 1988 even though P/B generally increased. • Accountants generally increased reactive conservatism until the dot-com boom. 46 Robustness/Alternate Explanations • Choice of the return period – fiscal year same • Hribar and Collins (2002) direct cash flow – similar results post-87 • Market inefficiency – Fama and French (1992) negative cross-sectional association between P/B and security returns – we don’t see how this can explain results 47 Conclusions, Limitations, Future Research (1) Earnings conservatism is negatively associated with P/B – Given an overall level of conservatism embedded in accounting standards, accountants and managers wax more conservative when we need them to – here, proxied by P/B decreases – Both overall conservatism and reactive conservatism vary over time • Enrons, new governments • Litigiousness 48 Conclusions, Limitations, Future Research (2) The link between earnings and balance sheet conservatism is mainly due to the accrual component of earnings, not the operating cash flow component of earnings. (3) Accruals implement reactive earnings conservatism: Cash flow conservatism exists, but is unrelated to P/B. 49 Future Research • Compare earnings conservatism across countries – Allow for cross-country variation in the relation between earnings conservatism and P/B. • We conjecture that variation in the institutional features that give rise to conservatism also results in cross-country variation in responsiveness the association between earnings conservatism and balance sheet conservatism. – legal systems – insider trading regulations – accounting standard setting mechanisms 50 Future Research • Possibly, one could revisit Dechow/Dichev (2002) and see if conservatism increases or decreases the mapping of accruals into past, present, and future cash flows. The research tension: – Conservatism delays earnings recognition until cash receipts are more verifiable; ignores “irrational exuberance” – Conservatism biases earnings recognition away from timely and neutral reflection of market perceptions. 51