INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS Kate

advertisement

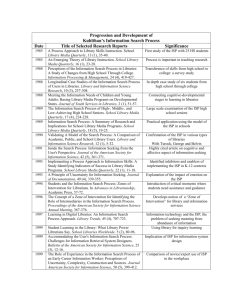

INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS Kate Reid 1 December 8, 2013 The Information Behavior of Middle School Students in an Academic Context Introduction In the course of their academic lives, middle school students seek information, learn new facts and ideas, and apply their new knowledge. In order for librarians and libraries to serve middle school students in the best possible manner, a clear and in-depth understanding of the information behavior of middle school students is needed. Why do they seek information? What kind of sources and media do they prefer? How do they formulate their queries? How do they determine the relevance of the information they find? What role does the student’s prior knowledge play in his or her information-seeking behavior? By examining these questions and searching for answers, this paper will determine implications for libraries and information professionals. As well, the complex information behavior of middle school students in academic contexts will be explored. The exact grades comprising middle school vary depending on where one lives and attends school. For this paper, middle school refers to grades five through eight and ages nine through fourteen. During these years, students’ information behavior has been broadly categorized as: trying to find the ‘right’ answer as quickly as possible with the least amount of effort, aiming to ascertain what the teacher wants, and learning about an interesting topic (Hultgren & Limberg, 2003). The impetus for middle school children to seek information frequently stems from a teacher’s directive. Research for middle school students requires that they be able to read multiple documents and then be able to: identify the information source, compare information from different sources, and ultimately integrate all this information (Sullivan, 2011). The ubiquity of the INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 2 Internet demands that students be able to search effectively both in books and online. This paper will examine the information behavior of middle school students using technology as well as traditional print sources. Large and Beheshti (2000) found that students fall under the following categories, “technophiles, traditionalists, or pragmatists” (p. 1069). Todd (1998) delineated three dimensions and the processes associated with them that are essential to developing critical literacies. First, students need to connect with the world of information. By connecting with information, youngsters will question, define, search, and locate information. Second, students must interact with information. Interacting entails further questioning on the part of the student who will also challenge, evaluate, filter, analyze, interpret, synthesize, and critique the information. Finally, the student should utilize information by a myriad of processes. He or she may find help, get directions, solve needs, move on, implement an action, or construct a solution. Kuhlthau, Maniotes, and Caspari (2007) described the inquiry process as preceding the writing process. Through their inquiries, students discover information and then write about it. However, students often mistakenly believe that the goal of their inquiry is to locate sources, collect information, and ultimately make presentations. Students and their instructors all too often bypass real exploration and formulation of focused ideas. Kuhlthau et al. (2007) found that “the most important task of the inquiry process is to explore the information and ideas within sources and to form new understanding from these ideas” (p. 22). Literature Review The cognitive perspective provides a solid framework upon which to construct an understanding of middle school students’ information behavior. Gross (1999) expounded on the helpfulness of Taylor’s model of formulating a question. Taylor’s model allows for a process that evolves as the seeker formulates his or her question. Just by verbalizing the question, the INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 3 student’s question may change. The question may mutate even further when the student tries either to put the question into search terms or vocabulary words suitable to the system he or she chooses to use. The cognitive school additionally allows for the student to seek, find and use new information such that their prior knowledge of a topic is modified (Cole et al., 2013). As Bilal (2005) pointed out, the cognitive viewpoint focuses on the seeker’s whole experience by examining their actions, thoughts, and feelings. As she wisely argued, Belkin’s ASK (anomalous states of knowledge) assumes that there is a gap in the seeker’s knowledge structure. The student seeks and acquires information to overcome this gap to the point that his or her state of knowledge undergoes change. In elaborating on Belkin’s ASK, Shenton and Dixon (2005) described a student who confronted a problem, such as a homework assignment, and realized that his or her existing knowledge was not enough to solve the problem. According to Belkin, the seeker, who in our case is a middle school student, experiences an anomaly that might be a gap, a lack, incoherence, or uncertainty. In the process of seeking information to solve the problem, the student may struggle at first to express exactly the information that he or she needs. During the student’s search, “the information gathered causes the individual’s state of knowledge to change, and increasingly, a clearer grasp of what is required is developed” (Shenton & Dixon, 2005, p. 22). The constructivist perspective examines the student in context. Much of the most recent research on the information-seeking behavior of youths has focused on the importance of studying students in context. Crow in 2011 reported on intrinsically motivated fifth graders. She discovered that the students in her research pool did not come from advantaged family backgrounds, but they did all have anchor relationships. That is, each of these fifth graders had people, family members or other adults, who supported their natural interests and their INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 4 information seeking. Children constantly learn and construct meaning by interacting with the people around them. Kuhlthau et al. (2007) cogently explained the social constructive experience of students who continuously learn by interacting with their parents, siblings, teachers, and fellow students. A move from concrete to abstract thinking takes place during the middle school years. Students explore ideas from myriad sources and then need to integrate this new information with what they already know. They learn how to develop a focus while seeking information. Ultimately, they share and apply the assimilated information (Kuhlthau et al., 2007). They often begin middle school by thinking in concrete terms and looking for highly specific information. Shenton and Dixon (2005) reported of one nine year old, Ian, who had a quick reference question, “‘how many stars are there in the galaxy?’” (p. 23). As students move further into their middle school education, they need to develop critical thinking skills and be able to think more in the abstract (Cole et al., 2013). The current mandate of many educators is for middle school students to formulate research questions that have multiple explanations and about which the student will ultimately form a reasoned opinion (Enochsson, 2005). In the knowledge society in which they live, students need to develop higher order thinking. Simple fact-finding skills are not enough. Bowler, Large, and Rejskind (2001) outlined Bloom’s educational objectives in the cognitive realm. The following, ranked from lowest to highest, delineates the cognitive skills students need to develop: – – – – – – Knowledge – the ability to identify, recall and recognize. Comprehension – the ability to explain, restate, demonstrate. Application – the ability to apply, generalize, organize, and restructure knowledge. Analysis – the ability to categorize, distinguish, deduce, compare. Synthesis – the ability to produce, develop, write or tell Evaluation – the ability to justify, judge, argue and assess (p. 205). INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 5 During middle school, students learn to use information critically, to gain deep understandings of the information they discover, and to produce knowledge creatively. To accomplish these skills requires the last three of Bloom’s educational objectives. Analysis, synthesis, and evaluation demand higher order thinking by the student. Active learning. In order for the student to be able to question, evaluate, and synthesize information, he or she must be actively engaged with it (Bowler et al., 2001). One fifth grader in Crow’s (2011) study perfectly expressed the importance of active engagement, “’I like learning, but I mean it gets kind of boring sometimes, but researching stuff is like the best, doing projects. Holy cow, that’s really fun’” (p. 13). This boy did not even think of information seeking as learning, it was just something fun and interesting to do. Throughout the literature on information-seeking behavior in middle school, students echoed his thoughts. They constantly mention the importance of interest in a topic as integral to making the research process easier (Enochsson, 2005). Sullivan et al. (2011) pointed out that educators have increasingly recognized the importance of active inquiry and interaction with a variety of texts and sources. The Information Search Process (ISP) Kuhlthau’s (1991) model of the information search process (ISP) forms the ideal cornerstone for studying middle school students’ information-seeking behavior in academic contexts. This model, see Table 1, represents the seeker’s physical actions, affective feelings, and cognitive thoughts. In this model, the student actively engages in a sense-making process and forms meaning from information. The student’s information search is a constructive process that involves his or her thoughts, actions, and feelings. The student extends his or her knowledge of a topic through “a series of encounters with information within a space of time rather than a INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 6 single reference incident” (Kuhlthau, 1991, p. 361). The student assimilates information from multiple sources with what he or she already knows. Ultimately, the ISP ends with the student gaining a new understanding to be presented to others. Kuhlthau, Maniotes, and Caspari (2007) developed the Guided Inquiry approach to accompany the ISP. In Guided Inquiry, the student, with intervention from librarians and teachers, actively engages with sources, asks questions, challenges information, explores, gains knowledge, and reaches solutions. TABLE 1. Information Search Process (ISP) (Kuhlthau, 1991, p. 367) Two aspects central to Kuhlthau’s ISP are the formulation of a focus and the role of affect. In the initial middle school years, the focus is frequently assigned when the teacher gives a narrow research topic such as the 2012 U.S. men’s Olympic gymnastics team. However, as students progress through middle school, they need to form foci themselves as they research more general subjects. If students fail to form a focus or develop a critical attitude, they may merely gather a bunch of unrelated facts (Kuhlthau et al., 2007). Bowler et al. (2001) emphasized that for students to be actively engaged in information seeking they must be emotionally as well as intellectually involved in the process. Bilal (2005) further argued that INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 7 affect gives directionality to learning that subsequently impacts actions. The holistic approach of the ISP involves the whole child; “students’ feelings have as great an impact on how they pursue their inquiry as their thoughts and their actions” (Kuhlthau et al, 2007, p. 140). Stage 1 – Initiation. In the first stage of the ISP, the student discovers a gap in their knowledge. This gap frequently is in the form of a research assignment for a paper or a presentation. The student recognizes that they lack knowledge to complete their schoolwork. They contemplate the problem, work to understand what they need to do, and try to relate the problem to any prior knowledge they may have. They begin to seek background information. Feelings of uncertainty and anxiety are common at this initial stage (Kuhlthau, 1991). The assignment itself will have an impact on the student’s information seeking. If the assigned topic is too vague, especially for younger middle school students, then finding a focus will be difficult and uneasy feelings will abound. As well, students need to be instructed that they will have plenty of time in which to complete their search (Hultgren & Limberg, 2003). Stage 2 – Selection. Students choose a topic to research. After they have selected their topic, they feel optimistic about the project and are ready to begin researching. However, the process of selecting the topic is not an easy one. Students make their selection based on the following criteria: personal interest, available information, the instructor’s requirements, and the amount of time they are given to work on the project (Kuhlthau, 1991). In an article on gifted seventh graders, Thompson and Seward (2012) recounted that these students were not allowed to choose a topic about which they had too much prior knowledge. They had to determine that they would have access to sufficient resources to support their chosen topic of study. During this step of topic selection, “many students soon discover that this initial stage is the most difficult portion of the assignment” (Thompson & Seward, 2012, p. 69). In their preliminary searching, students INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 8 consult teachers, librarians, and peers. They skim general reference sources to identify other possible topics. At this early stage in the ISP, general reference books such as encyclopedias provide students with excellent overviews. In a study of ten fifth-grade students doing projects on sports figures, Hirsh (1999) discovered that at the beginning of the research process the students focused on seeking basic biographical facts. Kuhlthau et al. (2007) expounded that books and magazines are helpful to students for more detailed information and differing viewpoints. The sequence of beginning with general reference materials before moving on to books and magazines, “introduces students to the layers of information that build knowledge” (Kuhlthau et al., 2007, p. 65). Librarians have noted that gifted and talented sixth graders can become bogged down in the stacks when they skip the step of consulting the reference section (Kopfer, Olwell, & Hudock, 2005). Stage 3 – Exploration. During this stage of the ISP, students search for information on their topic. Their thoughts become sufficiently well informed that they begin to formulate a focus. Nevertheless, many students find it difficult to communicate to the system, be it a search engine or a librarian, what information they seek. They continue to find information, to read about their topic, and to relate the newly discovered information with what they already know. Feelings of confusion, frustration, doubt, and discouragement are common (Kuhlthau, 1991). A student naturally tends to believe that he or she is the only one to experience this anxiety. It is a relief for the student to discover that others feel this same uncertainty (Kuhlthau et al., 2007). Not surprisingly, information needs sometimes shift during the ISP. Shenton and Dixon (2005) found that most of the middle school students in their research group remained focused on their original topic. However, students at times needed to redefine their topics. One eleven INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 9 year old had to change her topic from focusing on the veterinarians to animals in general because she originally held misconceptions of what information was available. Kirsty, aged thirteen, similarly broadened her research from poltergeists to the broader concept of ghosts. Poor research skills might lead students to change their topics. In another project, Kirsty more drastically changed her topic from the moon to rockets and other space vehicles because she located information more readily on rockets. These types of needs, “where what is actually desired is reshaped by youngsters in accordance with their perception of what is available, may be understood as a form of the ‘compromised need’ described by Taylor” (Shenton & Dixon, 2005, p. 22-23). Stage 4 – Formulation. Many middle school students face a barrier between stages 3 and 4 of the ISP. They have difficulty transitioning from their topic and the information they have learned to generating new knowledge and building a thesis or critical viewpoint (Cole et al., 2013). Stage 4 involves the students forming a focus. They formulate a personal perspective on the topic from the information they have located and absorbed. Feelings of anxiety tend to subside while a sense of confidence increases (Kuhlthau, 1991). Making this step demands hard work from the middle school student. In their study of sixth graders, Kopfer et al. observed that students needed direction in thinking about their search as an iterative process. Illustrating Kuhlthau’s zone of intervention,* they pointed out that children at this age need guidance creating and refining their questions (Kopfer et al., 2005). Students in Enochsson’s (2005) study reported how easy it was for them just to ‘surf around’ if they lacked a focus. Middle school students need specific goals and perspectives. * For more information on the zone of intervention, see page 11 of this paper. INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 10 Stage 5 – Collection. At the collection stage, the information seeker interacts effectively and efficiently with the system. The student gathers information directly related to their nowfocused topic. In an iterative process, they define and support their perspective. Students should be taking detailed notes from the sources on their focused subject, as they should have all of the general background information that they need. Kuhlthau surmised that the information seeker’s confidence rises and their anxiety decreases during this gathering step (Kuhlthau, 1991). For example, by the third and fourth research sessions of sixth grade students doing a research project, the children were able to identify useful information and stay focused on their assignment. The students evaluated the information as they located it and decided whether or not to take notes from the found source. Students at this stage assess the utility of the information collected and develop a personal meaning for the information. In order to evaluate productively, students need the skills to determine the “accuracy, validity, relevance, completeness and impartiality of information” (Bowler et al., 2001, p. 212). Hirsh (1999) found that as fifth graders neared the end of a research project, their reliance on topicality as a criterion for relevance decreased. Instead, students concentrated on interesting and new information. Stage 6 – Presentation. At the end of the ISP, students complete their information seeking and prepare their materials for some sort of presentation, often a written paper or oral report. Ideally, they concentrate on ending the search by applying personal meaning to the information they have found, integrated, and analyzed. As they organize their notes and finalize their presentations, students either feel relief and satisfaction if all has gone well, or they are disappointed if they have not had success in their ISP (Kuhlthau, 1991). Students terminate their information seeking usually for two reasons: they either find what they need, or the submission date itself ends the ISP. In creatively using their research, students communicate an idea INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 11 effectively and appropriately. The convincing presentation demonstrates a cohesive synthesis of their discoveries. The hope is that students will make decisions about how to create a product that reflects their own thinking and is not just “the regurgitation of someone else’s thoughts” (Bowler et al., 2001, p. 217). Zone of Intervention. A critical implication of the ISP for the librarian is Kuhlthau’s notion of the zone of intervention. Throughout the search process, times occur when the student needs appropriate guidance. It may mean, for example, at the initiation stage that middle school students need instruction on the layout of the library, on how to perform effective Internet searches, or how to use a book’s index successfully. With Guided Inquiry, students are provided assistance when they reach a point when they can no longer seek information by themselves or they can only do so with significant difficulty. In order to refrain from offering unnecessary advice, the librarian must develop the skill to recognize when intervention will be beneficial and when it will be a hindrance (Kuhlthau et al., 2007). The Imposed Query Although students need guidance, the vast majority of the literature on their information behavior demonstrates that they engage more actively with their research if they choose their own topic within a curriculum area (Bilal, 2005; Cole et al., 2013; Crow, 2011; Kuhlthau et al., 2007). Students routinely receive questions and assignments from their teachers. Gross (1999) developed the Imposed Query Model, see Figure 1, from professional observation. In this model, information seeking is either imposed (e.g. an assignment from a teacher) or is selfgenerated. Imposed queries occur in context, examples of which include a science experiment, a project, a reading assignment, or a research paper. For imposed queries, middle school students frequently use the library per the teacher’s directions. INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 12 Stage 1 – Initiated. At this beginning stage, the teacher communicates to the student a question or assignment for the student to complete. The teacher may indicate where applicable information is located or in what form the assignment should be completed (Gross, 1999). The question itself will guide students’ information seeking. ‘Why’ questions will demand more analytical skills from the students; whereas, ‘what’ and ‘how’ questions will lead the students to more fact-based answers. In one study, sixth graders referred back to their teacher’s initial questions throughout their research: “The questions were like a thread woven throughout the project. The final product, the poster, was a direct reflection of the information need created by the questions” (Bowler et al., 218). Fifth graders in another study sought information on a concrete topic, a sports figure. Hirsh (1999) deemed this to be fitting because they were still in “Piaget’s concrete-operational stage of development” and thought in concrete terms. Even though, it was an imposed query, it was one of great interest to the children who were excited to begin the project. Stage 2 – Transferred. Communication is a critical aspect of the Imposed Query model. In order to understand the actions he or she needs to take, the student must understand the query. Otherwise, the student may not be able to complete successfully the assignment or may not ever INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 13 develop a focus. Interestingly, the personalities and interests of the imposer and the agent come into play at this stage. Gross (1999) explained that “perceptions of ownership for imposed queries varied, even among students transacting identical questions, that is, the same assignment from the same teacher ” (p. 502). Stage 3 – Interpreted. The student hopefully internalizes the query at this stage. The more a student takes ownership of the project, the more positive will be their informationseeking experience. For students who do not grasp what is intended, then the arrow back to the imposer illustrates that they return to the teacher/imposer for clarification (Gross, 1999). Stage 4 – Negotiated. Communication again merits great importance. At this stage, the imposer/teacher, the intermediary/librarian, and the agent/student all interact and benefit if they understand each other. The feelings and beliefs each actor has for the other come into play. How approachable is the librarian? What is the relationship like between the librarian and teacher? How comfortable is the student asking questions? These factors will impact how much the intermediary understands the student’s search and what kinds of sources the student will be directed to use (Gross, 1999). As Hultgren and Limberg (2003) lucidly illustrated, “there is a greater risk of misunderstanding, the pupils do not really know what they are looking for and librarians are faced with interpreting teachers’ instructions through pupils’ often confused understanding of the research problem” (p. 3). Stage 5 – Processed. Ideally, students now have even more ownership of the query. They continue to research. Prior interaction with teachers and librarians provides them with clear understandings of how to locate information and what kinds of information to seek. As students become more and more familiar with their topics, they select material they find to be relevant and interesting (Hirsh, 1999). INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 14 Stage 6 – Evaluated. The student completes the assignment and submits it to the teacher for the teacher to evaluate. Part of the evaluation entails the teacher’s response to the student’s understanding of the query initially imposed by the teacher. Gross (1999) stressed that the query is in danger of changing during every stage of the process. She additionally found that children face a number of hindrances during the information seeking process. These hindrances include limited reading abilities, poor search strategies, and weak critical analysis skills. Hultgren and Limberg (2003) addressed some of the negative consequences of imposed queries.† If teachers assign poorly designed research projects, then the students’ interest may or may not be engaged. This in turn leads pupils to accept uncritically the first information sources they discover. If they do not locate relevant sources, they may too readily change their focus to adapt to the information that they do find. Finally, plagiarism may result if the students are given a deadline that does not allow enough time for information seeking. Students require support and structure from librarians and teachers to deepen their understanding of a topic. A final consequence of the imposed query is that students skim quickly for specific facts instead of reading texts deeply. Sources Consulted by Middle School Students. Middle school students consult myriad sources in the course of their academic lives. Their main information sources are their own prior knowledge, school libraries, printed texts (including reference works, books, magazines, journals, and textbooks), teachers, their peers, and sources found on the Internet. All of the fifth graders interviewed in Crow’s 2011 study indicated that they used at a minimum two types of media; all but one reporting using three media types. Crow found as well that students initiated their searching with the media that was † Hultgren and Limberg’s (2003) study involved a wide range of ages and grades. However, their conclusions apply to middle school students. INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 15 most accessible to them and with which they had the most experience. After developing knowledge from one source, they then expanded their seeking to include other sources and media types. Books. Despite the pervasiveness of the Internet, middle school students still use traditional sources for much of their information seeking. Crow wrote in 2011, “studies have shown that children are not as successful nor as motivated by computer use as the conventional wisdom would suggest” (p. 27). The middle school students in her research group did not say that they disliked or lacked experience using computers; rather they simply chose other media sources. All but one of these fifth graders began their research with books or other printed media and later used the Internet for supplemental information. In an earlier study, Bowler et al. (2001) reported of one child who thought searching on the Web took too long. He preferred the straightforward presentation of information in books. As the boy articulated, “using books is ‘not that hard, because you just have to look in alphabetical order’” (p. 210). Other studies reached similar conclusions, students appreciate the organizational structure of books, including chapter outlines, indexes, and the alphabetical order of encyclopedias (Large & Beheshti, 2000). However, middle school students do not always know how to use indexes effectively. Nor do they innately know how to think of alternative search terms when looking in an index or a library catalogue. They frequently conclude that information on a topic does not exist if they cannot locate it (Kuhlthau et al., 2007). Hirsh (1999) explained that, because fifth graders are in Piaget’s concrete-operational stage, they seek results that exactly match their topic. For example, they preferred books whose titles explicitly included their topic. Peers. Middle school students find their peers to be approachable sources of knowledge and of help. Hirsh (1999) viewed the fifth graders who he studied as being supportive of each INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 16 other. They frequently shared books, pictures, ideas, and other information. In another study of sixth graders working on computers, the children only asked for on-line help one time in seventy-eight sessions. They much preferred to seek assistance from knowledgeable peers (Large & Beheshti, 2000). Source Selection. As mentioned previously, many middle school students select sources based on its availability. They also consider other relevancy factors. They look for new and novel information. By far the most important factor is topicality, the information must relate directly to their topic. In Hirsh’s (1999) study, middle school students preparing for an oral presentation exhibited concern that the information would be of interest to their peers. In all of the articles examined for this paper, students demonstrated scant concern for up-to-date information. Prior/Implicit Knowledge. Middle school students build deep understanding by synthesizing past experiences and prior knowledge with new information – a point stressed by constructivist theory (Kuhlthau et al., 2007). At the early step of making proposals, Cole et al. (2013) found that students with implicit knowledge received high marks. Background experience of a subject usually serves as a predictor of student success on a project. Students use what they already know about a topic, incorporate this knowledge with new information, and develop a critical point of view on their topic. Students may be unaware that they have this knowledge, for example they may unwittingly employ already known, useful terminology when searching tables of content and indexes (Hultgren, 2003). Research has established that middle school students who have higher prior knowledge are better able to navigate text and process ideas. In hypertext environments, they “have been found to be more proficient with navigating INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 17 to content directly related to the learning task and to conduct deeper investigations into the content and affordances of the hypertext system” (Sullivan, 2011, p. 393). Electronic Information Behavior of Middle School Students. As early as 2005, Large claimed that the Web was available at “almost every school throughout North America” (p. 366). The research literature examined for this paper paints a complex picture of middle school children’s use of technology in their academic information seeking. Students expressed frustration, appreciation, sophistication, and ambivalence when consulting online sources. Large and Beheshti (2000) made the cogent point that the Internet is not an information source in and of itself; rather, the Internet is a “gateway to millions of sources from millions of information providers, most of which are not intended specifically for children, some of which might be considered very unsuitable for them, and a tiny part of which may be highly relevant for an assigned class project” (p. 1069). Frustrations. Middle school students’ frustrations with using the Internet for assignments may be categorized as follows: difficulty formulating appropriate search terms, being directed to the same link repeatedly, misleading links, information overload, unfamiliarity with different search engines, and not easily finding relevant information. Bowler et al. (2001) emphasized the need for children to gain technical literacy for effective information seeking in the unstructured Internet environment. This holds true in 2013. In early exploratory search sessions, young users tend to take few notes, lack a strategic search plan, and skip over sites that directly answer their queries. They exhibit engagement but simultaneously speed through multiple links thereby missing relevant information (Hultgren, 2003). Although middle school students are frequently admonished to take detailed notes and to keep track of their sources, this task is not an easy one for them. Whether they are browsing INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 18 online or in books, they tend to avoid keeping accurate logs of sources, which leads to later problems with citation or returning to an information source. As well, they struggle in determining what to write down. Students “frequently either make the mistakes of attempting to write down everything or of taking sparse notations that are not useful when they refer back to them” (Kuhlthau et al., 2007, p. 89). Search Terms. Middle school students regularly encounter roadblocks at the beginning of their search processes because they have difficulty formulating appropriate terms for search engines. They moreover have trouble revising their strategies (Large, 2005). However, search engines have become more user-friendly since many of the articles consulted for this paper were written. Nevertheless, Boolean search terms remain an enigma to most middle school students. In 2005, Enochsson reported pupils using quotation marks, subtraction and addition symbols, capitalized versus uncapitalized letters, and experimenting with the space bar. A couple of studies found that with both experienced and inexperienced online searchers, students preferred using broad search terms, made spelling mistakes, and did not comprehend how to create focused searches (Bowler et al., 2001; Hirsh, 1999). Enochsson (2005) established that children themselves recognized the importance of reading and language skills when information seeking.‡ Sullivan (2011) confirmed that middle school students with higher comprehension abilities used navigation strategies more and more effectively than did those who had weaker comprehension skills. Online Searches. Not only do they often have difficulty formulating their searches, but also middle school students often repeat the same search over and over again. They rarely bookmark or keep records of sites which can lead to spending a good deal of time trying to ‡ Enochsson (2005) created a non-linear model of children’s Web searching skills. Please see the appendix. INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 19 relocate a useful website. Hirsh’s (1999) fifth grade students frequently could not reconstruct their prior searches. Bowler et al. (2001) similarly found that sixth graders unwittingly looped back to previously visited sites, even if they selected what appeared to be a new link. Bilal’s 2005 study concluded that students relish the availability and flexibility of online searching. They enjoy the graphics, the convenience, and the inputting of keywords. Children think that using technology is a fun way to search and to learn. Bilal (2005) referenced her own 2003 article in which she explained, “children prefer search engines that are designed for adult users such as Google, Alta Vista, AskJeeves, and Yahoo” (p. 202). Enochsson (2005) similarly found that many students had favorite search engines with the awareness that they might retrieve different pages depending on what engine they used. One problem encountered by middle school students when performing online searches lies in taking notes on the masses of information they retrieve. Many scholars describe the lure to plagiarize without constructing personal meaning. (Bowler et al., 2001; Kuhlthau et al., 2007; Large & Beheshti, 2000; Thompson, 2012). Not only is plagiarism prevalent, but also is the propensity to improperly evaluate electronic sources. For the most part, students at this age know to steer clear of unofficial sites, however they lack the skills or inclination to assess the accuracy, validity, and authority of websites (Bowler et al., 2001; Hirsh, 1999; Large & Beheshti, 2000; Shenton, 2005). The School Library. Despite the widespread use of computers and information seeking on the Internet, middle school students continue to make much use of school libraries. As recently as 2011, Crow found that students consulted libraries both to seek information and to find books for pleasure reading. Middle school students ask librarians to help them put together search queries, to improve INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 20 information-seeking strategies, and to locate materials (Hirsh, 1999). A misconception began in the 1990s and continues among some people today that the Internet would make libraries obsolete. Kuhlthau et al. (2007) opined, “The opposite has proven to be the case. Books, both fiction and nonfiction, continue to be major sources of information and ideas that students can find, evaluate and use. Library skills, more broadly conceived as information skills or information literacy, are essential for learning in the information age” (p. 63). Todd and Kuhlthau (2005) conducted an in-depth study of student learning in school libraries. Although their research involved students from grades three through twelve, their findings hold for middle school students. Over 13,000 students participated in their study; of those, over ninety-four percent claimed the library helped them in their information searches, in learning, and in getting good grades. The students additionally expressed appreciation for the help provided them in the library. The school librarian plays an integral role in middle school students’ ISP: “The school library, and particularly the initiating intervention of the school librarian, helps to engage students in an information needs/questioning process that enables them to start their research, focus their searches, get input on the scope of their projects, identify information needs, understand the nature of the task, and provide resource pathways” (p. 73). Implications for Libraries and Information Professionals Libraries filled with books, magazines, computers, Internet connection, and reference materials serve middle school students best. Throughout the research literature, students report seeking, finding, utilizing, synthesizing, and creating meaning from multiple sources in multiple formats. The school library should reflect this reality so that it is a place where deep, active, and personal learning takes place. INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 21 Students learn best when school librarians and teachers work together to structure assignments in which students are allowed some choice in choosing their topics. Librarians should be aware that students need enough time to conduct meaningful research and assimilate new knowledge. As well, libraries help most when they are structured in a way that allows for both group projects and individual information seeking. A middle school librarian serves the role of educator, guide, and gatekeeper. It is his or her responsibility to foster communication between all participants (teachers, assistant teachers, and students) in the inquiry process. Kuhlthau et al. (2007) wrote, “the librarian brings together resources from the school and from the community outside the school. The librarian’s communication with experts outside the school provides extensive resources for the inquiry unit” (p. 58). The librarian ensures that the library maintains an appropriate and plentiful collection to support students’ information needs. As well, he or she aids pupils to access topical material. Best practice for middle school research projects means that the students go at the beginning stages of an assignment for an instructional session with the librarian. At this time they learn: the layout of the library, how to use the card catalogue, information about bookmarking, and how to formulate effective search terms. The librarian refreshes the young people’s memory on what it means to plagiarize, on how to take notes, and on how to keep track of sources consulted. They work with the classroom teacher to establish an open, friendly rapport. They should strive to be approachable and use neutral, open-ended questioning as recommended by Dervin (Shenton, 2005, p. 27). Librarians need to recognize that middle school students are truly in the middle. They start middle school in Piaget’s concrete-operational stage but steadily move toward deeper processing and higher order thinking. It would be immensely helpful if librarians were cognizant of INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 22 Kuhlthau’s ISP and intervened at appropriate times to help the whole (thinking, feeling, acting) child. A number of researchers emphasized how important reading and comprehension skills are to the information search process. Librarians should keep alert to any reading difficulties students may exhibit. In regards to the Internet, middle school students use it frequently and for the most part enjoy searching via this medium. However, preteens and teens demonstrate a marked preference for using adult search engines and Web portals. By primarily using Google, Yahoo and Bing, they are exposed to rampant advertising and may be directed to disturbing or inappropriate websites. It would be ideal if librarians, educators, students, and technology experts worked together to develop a medium in which inappropriate, adult material was filtered out. Attempts such as Yahooligans! and Yahoo! Kids have not lasted. Bilal (2005) concluded that students enjoy: colorful designs, explicit instructions on how to perform functions for keyword and phrase searching, a Help feature, entertainment topics as well as educational ones, broad and specific subject categories, and links to external search engines. A most apt description of the school library comes from Kuhlthau et al. (2007), “the school library is an in inquiry laboratory that functions as an exploring space, practice room and workshop. It is more than a storage room for old books” (p. 63). In the book Guided Inquiry, one finds fabulous recommendations to create this ‘inquiry laboratory.’ Libraries need areas for small groups to work together, individual study spaces, places for talking, places for being quiet, moveable tables and chairs, flexible space, computers, books, magazines, and a gathering space for an entire class. INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 23 Conclusion The information behavior of middle school students in academic contexts is complex and multi-faceted. They utilize multiple media, including print and electronic sources as well as their peers, librarians and teachers, in their information seeking. Students achieve varied success in their searching and greatly benefit from the wise, friendly intervention of librarians. They need instruction and guidance as they search in books, encyclopedias, and on the Internet. The scholarly literature depicts a picture of students enjoying and being excited about information seeking and the learning process. The school library provides the ideal place for middle school students to actively learn; “the library is a place for learning activism, where the emphasis is on empowering students to use their minds well rather than merely being given the information without requiring any mental activity” (Todd & Kuhlthau, 2005, p. 82). Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process along with Gross’s notion of imposed queries provides an excellent framework from which to understand middle school students’ information behavior. Operating from a constructivist and cognitive perspective, Kuhlthau, Maniotes, and Caspari further developed the ISP in their book Guided Inquiry. The ISP, the Model of the Imposed Query, and the Guided Inquiry method all approach the whole student by addressing their physical actions, affective feelings, and cognitive thinking. These models illustrate the iterative nature of information seeking. As well, the information behavior of middle school students entails critical thinking, which is the “complex ability where critical scrutinizing in a logical sense is one part, and emotional aspects, which include, for examples, values and standpoints are another” (Enochsson, 2005). In the Internet age, Enochsson rightly reasons that critical processing further involves the ability to discern reliable information online and to INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS understand a variety of perspectives. Developing critical thinking is a challenging yet integral part of the information behavior of middle school students. Students in grades five through eight appear to strive innately for a balance in their information seeking. For the most part, they consult a variety of both print and electronic sources, ideally beginning with general reference works. They enter middle school preferring concrete fact searching but move to higher order thinking. For significant learning to occur, students do not just locate, gather, and present information; rather they engage in deep thinking by making connections, taking ownership of the research process, seeking help when needed, forming a focus, and ultimately emerging from the process with new knowledge and understanding. 24 INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 25 References Bilal, D. (2005). Children’s information seeking and the design of digital interfaces in the affective paradigm. Library Trends, 54(2), 197-208. Bowler, L, Large, A., & Rejskind, G. (2001). Primary school students, information literacy and the Web. Education for Information, 19(3), 201-223. Cole, C., Beheshti, J., Large, A., Lamoureux, I., Abuhimed, D., & AlGhamdi, M. (2013). Seeking information for a middle school history project: The concept of implicit knowledge in the students’ transition from Kuhlthau’s stage 3 to stage 4. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(3), 558-573. Crow, S. R. (2011). Exploring the experiences of upper elementary school children who are intrinsically motivated to seek information. School Library Research, 14. Retrieved from: http://www.ala.org/aasl/sites/ala.org.aasl/files/content/aaslpubsandjournals/slr/ Vol14/SLR_ExploringtheExperiences_V14.pdf Enochsson, A. B. (2005). The development of children’s Web searching skills – a non-linear model. Information Research, 11(1). Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/111/paper240.html Gross, M. (1999). Imposed queries in the school library media center: A descriptive study. Library & Information Science Research, 21(4), 501-521. Hirsh, S. G. (1999). Children’s relevance criteria and information seeking on electronic resources. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 50(14), 1265-1283. Hultgren, F. & Limberg, L. (2003). A study of research on children’s information behavior in a school context. The New Review of Information Behaviour Research. 4(1), 1-15. INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 26 Kopfer, L, Olwell, R. B., & Hudock, S. (2005). Charting the library: Middle school and college students explore research strategies through mentoring. Research Strategies 20(1-2), 35-43. Kuhlthau, C., Maniotes, L. K., & Caspari, A. K. (2007). Guided Inquiry: Learning in the 21st Century. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited. Kuhlthau, C. C. (1991). Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 361-371. Large, A. (2005). Children, teenagers, and the Web. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 39(1), 347-392. Large, A. & Beheshti, J. (2000). The Web as a classroom resource: Reactions from the users. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 51(12), 1069-1080. Shenton, A. K. & Dixon, P. (2005). Information needs: Learning more about what kids want, need, and expect from research. Children and Libraries, 3(2), 20-28. Sullivan, S., Gnesdilow, D, & Puntambekar, S. (2011). Navigation behaviors and strategies used by middle school students to learn from a science hypertext. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 20(4), 387-423. Thompson, S. B. & Seward, V. (2012). Learn to do something new: Collaboration on McNair Middle School’s Independent Study offers fresh skills for gifted students. Knowledge Quest, 40(4), 68-72. Todd, R. J. & Kuhlthau, C. C. (2005). Student learning through Ohio school libraries, Part 1: How effective school libraries help students. School Libraries Worldwide, 11(1), 63-88. INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 27 Todd, R. J. (1998). From net surfers to net seekers: WWW, critical literacies and learning outcomes. Teacher Librarian, 26(1), 16-21. Retrieved from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/ehost/detail?vid=3&sid=8b50d2c3b64b-419f-95a7-3cd78fa95db6%40sessionmgr198&hid=116&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc 3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=eft&AN=502806849 INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS 28 Appendix Enochsson’s (2005) Non-Linear Model of Children’s Web Searching Skills. Note. Enochsson’s model does not view development in purely linear stages. It is a model of how young people seek information on the Internet in school settings. The students she consulted stressed the importance of basic language skills, computer skills, and the ability to think critically. In her model, as children mature they move out from the center of the spiral gaining skills and competence along the way. The spiral nature of the model emphasizes the recursive and iterative nature of development.