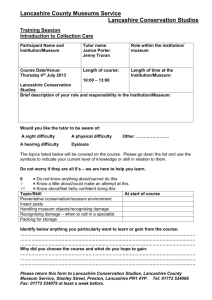

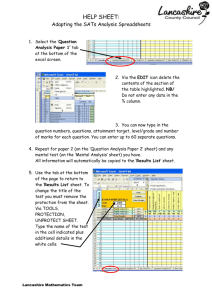

analysis of skills and employment issues in Lancashire

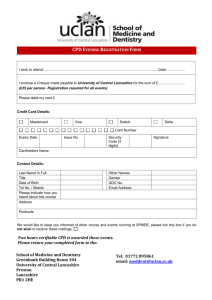

advertisement