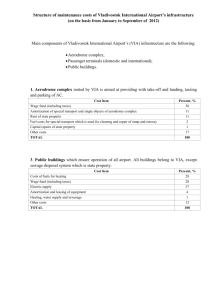

DOCX - Australian Transport Safety Bureau

advertisement