Document

advertisement

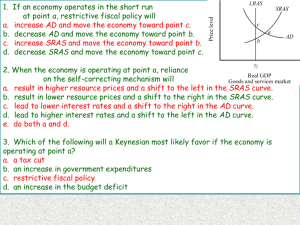

Adjustment to shocks and the role of government policies Ka-fu Wong School of Economics and Finance University of Hong Kong ** Prepared for the Professional Development Seminar for Economics Teachers, October 28, 2009. 1 Outline AS-AD model revisited Self-adjustment mechanism Time paths of output and price level Was Greenspan right in 1996 Long-run growth and inflation The role of the government The great depression and the recent crisis The passive role of Hong Kong 2 Exercise #1 Imagine yourself the central banker of a big country (such as the United States). Your objective is to maintain inflation within a narrow range with the policy tool of an overnight interest rate (such as the Federal fund rate). You have been seeing the following data lately. Years GDP Growth Unemployment Rate Inflation Rate 1985-1995 2.80% 6.30% 3.5 1995-2000 4.10% 4.80% 2.5 Would you choose to raise the target interest rate? 3 AS-AD model revisited Planned aggregate expenditure PAE = C + I + G + NX C=a1+a2(Y-T)+a3r+a4W I=b1+b2r NX = d1+d2q Real interest rate Real exchange rate Nominal exchange rate r=i-p q = ep*/p e = domestic currency per foreign currency p*= price of foreign good in foreign currency 4 Equilibrium output at a given price level Y = PAE 5 Determination of Short-Run Equilibrium Output Planned aggregate expenditure PAE Y = PAE Expenditure line PAE = 960 + 0.8Y Slope = 0.8 960 Equilibrium Algebraically • At equilibrium: Y=PAE • PAE = 960 + 0.8Y • Y=960+0.8Y • 0.2Y = 960 • Y = 960/0.2 = 4,800 in equilibrium 45o 4,800 Output Y 6 Aggregate Demand A relation between the equilibrium output and the price level. Y = PAE (p1) ⇒ Y1 Y = PAE (p2) ⇒ Y2 Y = PAE (p3) ⇒ Y3 … 7 The Aggregate-Demand curve Price Level (P) P ↓ ⇒ real wealth ↑ ⇒ consumption ↑ ⇒ interest rates ↓ ⇒ consumption ↑, investment ↑ ⇒ exchange rate ↓ ⇒ net export ↑ P1 P2 AD 0 Y1 Y2 Quantity of output (Y) 8 The short-run aggregate-supply curve Price Level (P) SRAS (Pe) P1 In the short run, P↓⇒Y↓ sticky wages, sticky prices, or misperceptions. P2 0 Y2 Y1 Quantity of Output (Y) 9 Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply Price Level (P) AS Output, Y, and the price level , P, adjust to the point at which the aggregate-supply, AS, and aggregate-demand, AD, curves intersect. P* AD 0 Y* Quantity of Output (Y) 10 The Long-run Aggregate-supply curve Price Level (P) LRAS P1 In the long run, Y depends on: labor, capital, natural resources, and technology. … but not on P. P2 Thus, the LRAS curve is vertical at YN. 0 YN Natural rate of output Quantity of Output (Y) 11 The Long-run equilibrium Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS In the long run, AD meets LRAS at point A. A P* Expected price level adjusts to equal the actual price level. AD 0 YN Natural rate of output Quantity of Output (Y) 12 Self-adjustment towards the long-run equilibrium Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS1 A P1 AD 0 Y2 Y1 Quantity of Output (Y) 13 Slow shifts in SRAS due to Long-term Wage and Price Contracts Union wage contracts set wages for several years. Contracts setting the price of raw materials and parts for manufacturing firms also cover several years. These long-term contracts reflect the inflation expectations or price level expectation at the time they are signed. 14 The Output Gap and Inflation Relationship of output to potential output Behavior of inflation 1. No output gap Y = Y* Inflation remains unchanged (Price level remains unchanged) 2. Expansionary gap Y > Y* Inflation rises 3. Recessionary gap Y < Y* Inflation falls (Price level rises) (Price level falls) 15 Self-adjustment of recessionary gap Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS1 SRAS2 SRAS3 A P1 B P2 AD 0 Y2 Y1 Recessionary gap Quantity of Output (Y) 16 Self-adjustment of expansionary gap Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS3 SRAS2 SRAS1 B P2 A P1 AD 0 Y1 Y2 Expansionary gap Quantity of Output (Y) 17 A Contraction in aggregate demand Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS1 SRAS2 A P1 B P2 C P3 AD2 0 SRAS3 Y2 Y1 AD1 Quantity of Output (Y) 18 Adjustment of output Y Y1 Y2 0 Time 19 Adjustment of price level P P1 P3 0 Time 20 Exercise #2 Impact of an increase in oil prices Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS2 SRAS1 Sketch the possible time paths showing the impact of this oil shock if the government and the central bank do nothing to accommodate the shock. B P2 C P1 AD1 0 Y2 Y1 Quantity of Output (Y) 21 An increase in oil prices Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS2 SRAS1 B P2 C P1 AD1 0 Y2 Y1 Quantity of Output (Y) 22 Adjustment of output Y Y1 Y2 0 Time 23 Adjustment of price level P P2 P1 0 Time 24 An increase in productivity (due to technological changes) Price Level (P) LRAS1 LRAS2 SRAS1 SRAS2 SRAS3 A P1 P2 B AD1 0 Y1 Y2 Quantity of Output (Y) 25 Adjustment of output Y Y2 Y1 0 Time 26 Adjustment of price level P P1 P2 0 Time 27 Exercise #1 Imagine yourself the central banker of a big country (such as the United States). Your objective is to maintain inflation within a narrow range with the policy tool of an overnight interest rate (such as the Federal fund rate). You have been seeing the following data lately. Years GDP Growth Unemployment Rate Inflation Rate 1985-1995 2.80% 6.30% 3.5 1995-2000 4.10% 4.80% 2.5 Would you choose to raise the target interest rate? 28 U.S. Macroeconomic Data, Annual Averages, 1985-2000 Was Greenspan right in 1996? Years % Growth in Unemployment Inflation real GDP rate (%) rate (%) Productivity growth (%) 1985-1995 2.8 6.3 3.5 1.4 1995-2000 4.1 4.8 2.5 2.5 29 Long-run growth and inflation Price Level (P) LRAS1980 LRAS1990 LRAS2000 P200 0 P1990 P198 0 AD2000 AD1990 AD1980 0 Y1980 Y1990 Y2000 Quantity of Output (Y) 30 Government intervention Short-run adjustments are painful! In the long run, we are all dead! 31 A Contraction in aggregate demand Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS1 SRAS2 A P1 B P2 C P3 AD2 0 SRAS3 Y2 Y1 AD1 Quantity of Output (Y) 32 Adjustment of output Y Y1 Y2 0 Time 33 The usefulness of fiscal and monetary policy A slow self-correcting mechanism Fiscal and monetary policy can help stabilize the economy. A fast self-correcting mechanism Fiscal and monetary policy are not effective and may destabilize the economy. The speed of correction will depend on: The use of long-term contracts. The efficiency and flexibility of labor markets. Fiscal and monetary policy are most useful when attempting to eliminate large output gaps. 34 Fiscal policies Government expenditure Taxation Takes time to pass a legislation Takes time to implement Supply-side policies Taxation 35 Monetary policy Interest rate Discount rate Reserve requirement 36 A Contraction in aggregate demand Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS1 A P1 B P2 AD2 0 Y2 Y1 AD1 Quantity of Output (Y) 37 Adjustment of output Y Y1 Y2 0 Time 38 An increase in oil prices with accommodation policy Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS2 SRAS1 A P1 B P2 C P3 AD1 0 Y2 Y1 AD2 Quantity of Output (Y) 39 Adjustment of output Y Y1 Y2 0 Time 40 An increase in productivity (due to technological changes) Price Level (P) LRAS1 LRAS2 SRAS1 SRAS2 SRAS3 A P1 P2 Do nothing! B AD1 0 Y1 Y2 Quantity of Output (Y) 41 The Fed’s Role in Stabilizing Financial Markets: Banking Panics Suppose: Depositors lose confidence in their bank. They attempt to withdraw their funds. Bank may not have enough reserves (fractional) to meet the depositors demand. The bank fails and further erodes depositor confidence which triggers additional failures. The Fed to the rescue: Instill confidence Discount lending Open Market Operations 42 The banking panics of 1930 - 1933 and the money supply One-third of U.S. banks closed Depositors withdrew their funds Banks raised the reserve-deposit ratio (banks were not willing to lend, considering loans too risky.) 43 Key U.S. Monetary Statistics, 1929-1933 Currency held by public Reserve-deposit ratio Bank reserves Money supply December 1929 3.85 0.075 3.15 45.9 December 1930 3.79 0.082 3.31 44.1 December 1931 4.59 0.095 3.11 37.3 December 1932 4.82 0.109 3.18 34.0 December 1933 4.85 0.133 3.45 30.8 44 The banking panics of 1930 - 1933 and the money supply In response to the panics of 1929-1933, deposit insurance was established in 1934. Deposit insurance gives depositors an incentive to keep their money in the banks. Deposit insurance reduces the incentive for depositors to pay attention to the financial strength of their bank. 45 Recent crisis: No response to expansionary monetary policy? Liquidity trap The demand for money becomes infinitely elastic, i.e. where the demand curve is horizontal, so that further injections of money into the economy will not serve to further lower interest rates. If the economy enters a liquidity trap area, monetary policy will be unable to stimulate the economy. 46 Recent crisis: No response to expansionary monetary policy? Credit rationing Banks maintain an interest rate lower than the market-clearing level. Excess demand for loans allows banks to choose the more profitable projects. When investment becomes more risky, banks are more cautious. Joseph E. Stiglitz and Andrew Weiss's 1981 paper explains why the bank (or any lending institution for that matter) may credit ration its borrower if 1) the bank was unable to perfectly distinguish the risky borrowers from the safe ones 2) the loan contracts were subject to limited liability (if projects returns were less than the debt obligation, the borrower bears no responsibility to pay out her pocket). Stiglitz, J. & Weiss, A. (1981). Credit Rationing in Markets with Imperfect Information, American Economic Review, vol. 71, pages 393-410. 47 What can the Fed do if Fed funds rate is near zero Fed can buy other assets such as treasury bonds or stocks (affect long interest rate) 48 Policymaking: Art or Science? Requirements for Perfect Macroeconomic Policy Accurate knowledge of current economic conditions Knowledge of the future path of the economy without policy The precise value of potential output Complete and immediate control of fiscal and monetary policy Knowledge of how and when the economy will respond to policy changes 49 Policymaking: Art or Science? Lags in the effect of macroeconomic policy: Inside Lag (of macroeconomic policy) The delay between the date a policy change is needed and the date it is implemented Outside Lag (of macroeconomic policy) The delay between the date a policy change is implemented and the date by which most of its effects on the economy have occurred 50 Policymaking: Art or Science? How to design macroeconomic policy? “Cross the River by Groping the Stone Under Foot” or “Feeling for rocks while crossing a river” “Feeling for rocks while crossing a river” connotes a gradual progress: When a step forward does not feel right, a step in another direction might be necessary. 51 The passive role of Hong Kong The linked exchange rate does not allow independent monetary policy Uncovered interest rate parity restricts Hong Kong’s interest rate to be very close to that of the US. 52 Impact of an expansionary monetary policy in the US Low US interest rate Low HK interest rate Investment and consumption Asset and property bubbles wealth effect? AD increases Y increases in the short long run P increases in the long run 53 Changes in aggregate demand due to changes in the US monetary policies Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS2 SRAS1 B SRAS3 A C AD3 0 Y3 Y1 Y2 AD1 AD2 Quantity of Output (Y) 54 Adjustment of output Y Y2 Y1 Y3 0 Time 55 Adjustment of inflation P P2 P1 P3 0 Time 56 Role of Hong Kong government? Monetary policy: By adopting the linked exchange rate system, we have given up our autonomy of monetary policy. Fiscal policy: We still have autonomy fiscal policy. It is tempting to use fiscal policy to accommodate the shocks. But fiscal policy is slow to take effect. By the time we see the effect, the US monetary policy might have shifted in the opposite direction. If so, the active HK’s fiscal policy may destabilize the output. Alternative: Make Hong Kong economy more flexible in adjusting to shocks. Improve the matching of job-seekers and vacancies. Encourage shorter job contract? Reduce the use of the government fiscal policy to stabilize the economy (government policies tend to be slow!) 57 End 58