File

advertisement

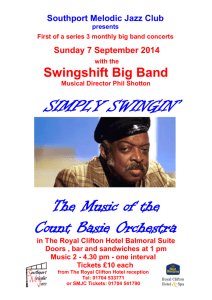

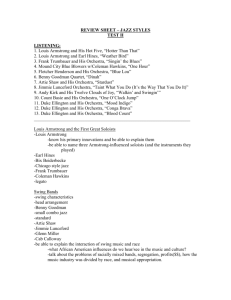

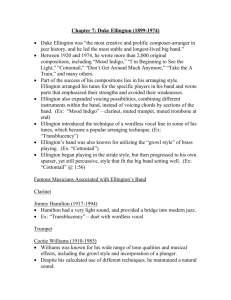

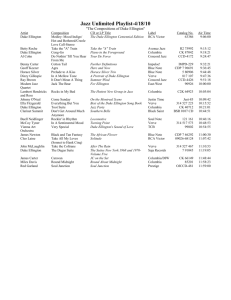

Ellington, Basie and others Count Basie (1904-1984) • Bill Basie studied music with his mother as a child and played piano in early childhood. He picked up the basics of early ragtime from some of the great Harlem pianists and studied organ informally with Fats Waller. He made his professional debut as an accompanist for vaudeville acts and replaced Waller in an act called Katie Crippen and her Kids. He also worked with June Clark and Sonny Greer who was later to become Duke Ellington’s drummer. Basie • It was while traveling with the Gonzel White vaudeville show that Basie became stranded in Kansas City when the outfit suddenly broke up. He played at a silent movie house for a while and then became a member of the Walter Page Blue Devils in 1928 and �29. Included in the ranks of the Blue Devils was a blues shouter who was later to play a key role as early male vocalist with Basie�s own big band, Jimmy Rushing. It was in fact the rotund Rushing who happened to hear Basie playing in Kansas City and invited him to attend a Blue Devil's performance. Basie soon joined the band after sitting in with them that night. Basie • After Page's Blue Devils broke up Count Basie and some of the other band members integrated into the Bennie Moten band. He remained with Moten until his death in 1935. After Moten�s death the band continued under the leadership of Bennie�s brother Buster, but Basie started a group of his own and soon found a steady gig at the Reno Club in Kansas City employing some of the best personnel from the Moten band himself. Basie • The band gradually built up in quantity and quality of personnel and was broadcast live regularly from the club by a small Kansas City radio station. It was during one of these broadcasts that the group was heard by John Hammond, a wealthy jazz aficionado, who had himself worked as an announcer, disc jockey and producer of a live jazz show on radio. Hammond decided that the band must go to New York. Through his efforts and support (at times even financially) the band enlarged its membership further and went to New York in 1936. Hammond installed Willard Alexander as the band�s manager and in January of 1937 the Count Basie band made its first recording with the Decca record label. Basie • By the following year the Basie big band had become internationally famous, anchored by the leader’s simple and sparse piano style and the rhythm section of Freddie Greene guitar, Walter Page bass, and Jo Jones drums. The great soloists of this band included Jimmy Rushing as vocalist, Lester Young and Herschel Evans tenor saxes, Earl Warren on alto, Buck Clayton and Harry “Sweets” Edison on trumpets, and Benny Morton and Dickie Wells on trombones, among others. Also contributing to the bands success were the arrangements by Eddie Durham and others in the band and the “head” arrangements spontaneously developed by the group. Basie • Despite the occasional losses of key soloists, throughout the 1940�s Basie maintained a big band that possessed an infectious rhythmic beat, an enthusiastic team spirit, and a long list of inspired and talented jazz soloists. Among the long line of budding stars to pass through the Basie aggregation's ranks during these years were tenor men, Lester Young, Herschel Evans, Don Byas, Buddy Tate, Lucky Thompson, Illinois Jacquet, and Paul Gonsalves. On trumpets the list includes Buck Clayton, Harry "Sweets" Edison, Joe Newman, and Emmett Berry. In the trombone section Dickie Wells, Benny Morton, Vic Dickenson, and J.J. Johnson all had stints with Basie in the 40�s. Basie • Except for a period in 1950 and �51, when economic conditions forced him to tour with a septet, Basie maintained a highly swinging big band that, at one time or another, included Clark Terry, Wardell Gray, Al Grey, Frank Wess, Frank Foster, Thad Jones, Sonny Payne, Joe Wilder, Benny Powell, and Henry Coker. In 1954 Joe Williams became the band's full time male vocalist. By 1955 he had infused the Basie band with new life and further commercial success beginning with Every Day I Have The Blues. Also during this period arrangers Neal Hefti and Ernie Wilkins contributed many fine swinging arrangements to the band's book. These great men of music coupled with Basie�s undying allegiance to the beat and the 12 bar blues allowed the band to consistently turn out records of extremely high caliber well into even the 1970�s. • Count Basie's health began deteriorating in 1976 when he suffered a heart attack that put him out of commission for several months. Following another stay in the hospital in 1981 he began appearing on stage driving an electric wheel chair. Count Basie died of cancer at 79. Kansas City Musicians • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Karrin Allyson Count Basie Buck Clayton Everette DeVan Herschel Evans Coleman Hawkins Pete Johnson Jo Jones Andy Kirk Julia Lee George E. Lee Harlan Leonard Jimmie Lunceford Jay McShann More K.C. Musicians • • • • • • • • • • • • Bennie Moten Hot Lips Page Walter Page Charlie Parker Sammy Price Jimmy Rushing Joe Turner Bobby Watson Ben Webster Claude Williams Mary Lou Williams Lester Young Duke Ellington (1899-1974) • pianist who was the greatest jazz composer and bandleader. One of the originators of big-band jazz, Ellington led his band for more than half a century, composed thousands of scores, and created one of the most distinctive ensemble sounds in all of Western music. • Ellington grew up in a secure middle-class family in Washington, D.C. His family encouraged his interests in the fine arts, and he began studying piano at age seven. He became engrossed in studying art during his high-school years, and he was awarded, but did not accept, a scholarship to the Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York. Inspired by ragtime performers, he began to perform professionally at age 17. Duke • Ellington first played in New York City in 1923. Later that year he moved there and, in Broadway nightclubs, led a sextet that grew in time into a 10-piece ensemble. The singular blues-based melodies; the harsh, vocalized sounds of his trumpeter, Bubber Miley (who used a plunger [“wa-wa”] mute); and the sonorities of the distinctive trombonist Joe (“Tricky Sam”) Nanton (who played muted “growl” sounds) all influenced Ellington's early “jungle style,” as seen in such masterpieces as “East St. Louis Toodle-oo” (1926) and “Black and Tan Fantasy” (1927). Duke • The expertise of this ensemble allowed Ellington to break away from the conventions of band-section scoring. Instead, he used new harmonies to blend his musicians' individual sounds and emphasized congruent sections and a supple ensemble that featured Carney's full bass-clef sound. He illuminated subtle moods with ingenious combinations of instruments; among the most famous examples is “Mood Indigo” in his 1930 setting for muted trumpet, unmuted trombone, and low-register clarinet. (Click here for a video clip of Duke Ellington and his band playing “Mood Indigo.”) In 1931 Ellington began to create extended works, including such pieces as Creole Rhapsody, Reminiscing in Tempo, and Diminuendo in Blue/Crescendo in Blue. He composed a series of works to highlight the special talents of his soloists. Williams, for example, demonstrated his versatility in Ellington's noted miniature concertos “Echoes of Harlem” and “Concerto for Cootie.” Some of Ellington's numbers—notably “Caravan” and “Perdido” by trombonist Juan Tizol—were cowritten or entirely composed by sidemen. Few of Ellington's soloists, despite their importance to jazz history, played as effectively in other contexts; no one else, it seemed, could match the inspiration that Ellington provided with his sensitive, masterful settings. Duke • Extended residencies at the Cotton Club in Harlem (1927–32, 1937– 38) stimulated Ellington to enlarge his band to 14 musicians and to expand his compositional scope. He selected his musicians for their expressive individuality, and several members of his ensemble— including trumpeter Cootie Williams (who replaced Miley), cornetist Rex Stewart, trombonist Lawrence Brown, baritone saxophonist Harry Carney, alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges, and clarinetist Barney Bigard—were themselves important jazz artists. (The most popular of these was Hodges, who rendered ballads with a full, creamy tone and long portamentos.) With these exceptional musicians, who remained with him throughout the 1930s, Ellington made hundreds of recordings, appeared in films and on radio, and toured Europe in 1933 and 1939. Duke • A high point in Ellington's career came in the early 1940s, when he composed several masterworks—including the above-mentioned “Concerto for Cootie,” his fast-tempo showpieces “Cotton Tail” and “Ko-Ko,” and the uniquely structured, compressed panoramas “Main Stem” and “Harlem Air Shaft”—in which successions of soloists are accompanied by diverse ensemble colours. The variety and ingenuity of these works, all conceived for three-minute, 78rpm records, are extraordinary, as are their unique forms, which range from logically flowing expositions to juxtapositions of line and mood. Tenor saxophonist Ben Webster and bassist Jimmy Blanton, both major jazz artists, were with this classic Ellington band. By then, too, Billy Strayhorn, composer of what would become the band's theme song, “Take the ‘A' Train,” had become Ellington's composing-arranging partner. Duke • Not limiting himself to jazz innovation, Ellington also wrote such great popular songs as “Sophisticated Lady,” “Rocks in My Bed,” and “Satin Doll”; in other songs, such as “Don't Get Around Much Any More,” “Prelude to a Kiss,” “Solitude,” and “I Let a Song Go out of My Heart,” he made wide interval leaps an Ellington trademark. A number of these hits were introduced by Ivy Anderson, who was the band's female vocalist in the 1930s. Duke • During these years Ellington became intrigued with the possibilities of composing jazz within classical forms. His musical suite Black, Brown and Beige (1943), a portrayal of African-American history, was the first in a series of suites he composed, usually consisting of pieces linked by subject matter. It was followed by, among others, Liberian Suite (1947); A Drum Is a Woman (1956), created for a television production; Such Sweet Thunder (1957), impressions of William Shakespeare's scenes and characters; a recomposed, reorchestrated version of Nutcracker Suite (1960; after Peter Tchaikovsky); Far East Suite (1964); and Togo Brava Suite (1971). Ellington's symphonic A Rhapsody of Negro Life was the basis for the film short Symphony in Black (1935), which also features the voice of Billie Holiday (uncredited). Ellington wrote motion-picture scores for The Asphalt Jungle (1950) and Anatomy of a Murder (1959) and composed for the ballet and theatre—including, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, the show My People (1964), a celebration of African-American life. In his last decade he composed three pieces of sacred music: In the Beginning God (1965), Second Sacred Concert (1968), and Third Sacred Concert (1973). Duke • Although Ellington's compositional interests and ambitions changed over the decades, his melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic characteristics were for the most part fixed by the late 1930s, when he was a star of the swing era. The broken, eighth-note melodies and arrhythms of bebop had little impact on him, though on occasion he recorded with musicians who were not band members—not only with other swing-era luminaries such as Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Coleman Hawkins but also with later bop musicians John Coltrane and Charles Mingus. Ellington's stylistic qualities were shared by Strayhorn, who increasingly participated in composing and orchestrating music for the Ellington band. During 1939–67 Strayhorn collaborated so closely with Ellington that jazz scholars may never determine how much the gifted deputy influenced or even composed works attributed to Ellington. Duke • The Ellington band toured Europe often after World War II; it also played in Asia (1963–64, 1970), West Africa (1966), South America (1968), and Australia (1970) and frequently toured North America. Despite this grueling schedule, some of Ellington's musicians stayed with him for decades; Carney, for example, was a band member for 47 years. For the most part, later replacements fit into roles that had been created by their distinguished predecessors; after 1950, for instance, the Webster-influenced Paul Gonsalves filled the band's solo tenor saxophone role originated by Webster. There were some exceptions to this generalization, such as trumpeter-violinist Ray Nance and high-note trumpet specialist Cat Anderson. Duke • Not least of the band's musicians was Ellington himself, a pianist whose style originated in ragtime and the stride piano idiom of James P. Johnson and Willie “The Lion” Smith. He adapted his style for orchestral purposes, accompanying with vivid harmonic colours and, especially in later years, offering swinging solos with angular melodies. An elegant man, Ellington maintained a regal manner as he led the band and charmed audiences with his suave humour. His career spanned more than half a century—most of the documented history of jazz. He continued to lead the band until shortly before his death in 1974. Duke • Types of Ellington compositions • Jungle Pieces: drums, muted instruments and effects to give character to floor shows at Cotton club (Caravan) • Dance Pieces (In a Mellow Tone, Don’t Get Around Much Anymore, It don’t mean a thing…, Sophisticated Lady) • Mood Pieces (Mood Indigo, In a Sentimental Mood) Duke • Solo Pieces (Features): Concerto for Cootie • Concert Works: most daring and not of the typical big band mode: Far East Suite, Liberian Suite, Togo Brava, Black, Brown and Beige (1943), A Rhapsody of Negro Life was the basis for the film short Symphony in Black (1935), which also features the voice of Billie Holiday (uncredited).