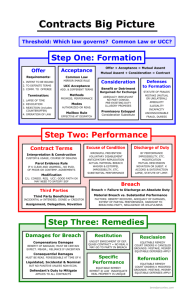

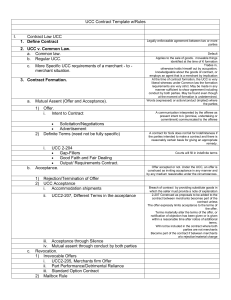

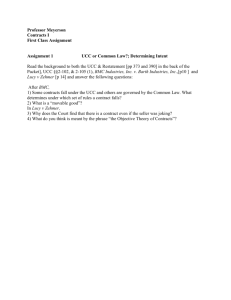

Contracts Outline

advertisement