Principles for Military Intervention

advertisement

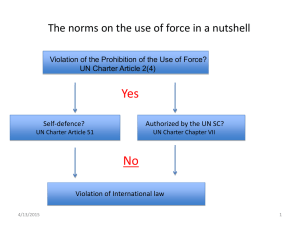

”The Ethics of War” 8.forelesning Jus ad bellum: When is resort to war morally justified? Just cause Right intention Legitimate authority Last resort Reasonable hope of success Proportionality Open declaration UN charter article 2 (4) All members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any othre manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations UN Charter cont. Paragraphs 42 and 51 of the UN Charter outline the conditions for when use of military force may be legal. § 42 states that: Should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in Article 41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may take such action by air, sea, or land forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security. Such action may include demonstrations, blockade, and other operations by air, sea, or land forces of Members of the United Nations. § 51 states that: Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security. Measures taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defence shall be immediately reported to the Security Council and shall not in any way affect the authority and responsibility of the Security Council under the present Charter to take at any time such action as it deems necessary in order to maintain or restore international peace and security. The Legalist Paradigm (Walzer) There exists an international society of independent states This international society has a law that establishes the rights of its members – above all the rights of territorial integrity and political sovereignty Any use of force or imminent threat of force by one state against the political sovereignty or territorial integrity of another constitutes aggression and is a criminal act Aggression justifies two kinds of violent response: a war of self-defence by the victim or a war of law enforcement by the victim and any other member of international society Nothing but aggression can justify war Once the aggressor state has been militarily repulsed, it can also be punished (Wars: 61-63). The UN definition of just cause (Luban) 1) A war is unjust if an only if it is not just 2) A war is just if it is a war of selfdefence (against aggression) The Domestic Analogy State’s rights are analogous with individual rights State’s rights to terrorial integrity and political independence are analogous with individual rights to life and liberty Hohfeldian relations 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) Wesley Hohfeld: Rights are relational concepts The right to life and liberty/independence and territorial integrity are claim-rights Claim-rights are always correlative with duties (Luban: ”Twoplace predicate”: Claims are always against someone) ”P has a claim-right to X” means the same as ”Q has a duty not to deprive P of X” To say that a state has a right to political independence and territorial integrity means that other states have a duty of not interfering To say that other states have a duty of not interfering means that a states has a right to political independence and territorial integrity The duty of Non-intervention A sovereign state has a claim against other states against intervention, thus by implication, there is a duty of non-intervention ”When state A recognizes state B’s sovereingty, it accepts a duty of non-intervention into B’s internal affairs” (Luban p.165) Any breach of the duty of non-intervention constitutes an act of aggression and is illegal Aggression ”Aggression is the use of armed force by a State against the sovereignty, territorial integrety and political independence of another State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Charter of the United Nations.” (UN definition of aggression 1974) Sovereignty Bodin: ”There can only be one ultimate source of law in a nation, the sovereign. Explains why intervention is a crime because dictatorial interference of a state in another state’s affairs establishes a second legislator” (Luban 164) - But why is the duty of non-intervention a moral duty? In other words, what is the moral standing of states? Can any state have a claim-right against others to not intervene? Or only legitimate states? What does it mean that a state is legitimate? Walzer on states’ rights The rights of states are derived from the rights of its citizens States’ rights are the collective form of ind.rights The metaphor of the contract: the rights of states rest on the consent of citizens When states are attacked, it is their members who are attacked, not only their lives but the sum of the things they value the most, including the political association they have made (Wars, 52) Walzer/Mill on selfdetermination States should be treated as self-determining political communities The members of a political community must seek their own freedom (just as the individual must shape his own virtue) Self-determination is the right of a people to become ”free by its own efforts”, and the principle non-intervention shall guarantee that their success is not impeded or their failure not prevented by foreign intrusion Three exceptions 1) 2) 3) Massacre and enslavement (Acts that ”shock the moral conscience of mankind”), e.g. genocide. Justifies humanitarian intervention Secession: two or more political communities contending within the same territory (i.e, two-nation states) If another foreign country has already intervened The legitimacy of the state We must explain how a violation of the rights of a state is also a violation of the rights of its citizens The contract metaphor: bridging the gap between collective and individual in terms of more or less explicit consent Luban’s criticism - - Walzer (and Mill) makes a category-mistake of mixing nations/political communities and states. Political communities are essential part of individual’s rights (shared ways of life, important values, what makes life worth living etc) But states (regimes) are not. States are regimes institutionalised, nothing in their own right The state may turn against its political communit(ies), consent may be absent In that case: The state is illegitimate The state has no claims against other states (because the claims of states are derived from the citizen’s rights via consent) The Modern Moral Reality of War (Luban) The identification of states with nations only works in the historical context of the nationstate When nations and states do not (necessarily) coincide, a theory of jus ad bellum which defines aggression in terms of sovereignty of states, removes itself from the moral reality of war Most wars today are wars of liberation, revolution, and civil wars The UN definiton of just cause is outdated Human Rights and the New Definiton (Luban) The UN definition should therefore be replaced: 1) A just war is (i) a war in defence of socially basic human rights (subject to proportionality); or (ii) a war of self-defence against and unjust war 2) An unjust war is (i) a war subversive of human rigths, whether socially basic or not, which is also (ii) not a war in defence of other basic human rights Basic Rights Socially basic rights are the rights that serve as necessary conditions for the enjoyment of other rights. E.g., the rights protecting access to basic needs to subsistence (food, security) Til diskusjon: krig for basisrettigheter A og B er naboland, atskilt av en fjellkjede. De er relativt like i styrkeforhold, men A er et fruktbart land ved havet, og fjellet fører til tørke i B. Et år blir det hungersnød i B, som truer millioner av liv. A nekter å gi B nødhjelp. Har B rett til å gå til krig mot A for å sikre seg mat? Til diskusjon: hjelp til selvhjelp - - I et land hvor regimet kontinuerlig undertrykker folket, kan man overlate til folket å redde seg selv? Hvilken rett til suverenitet har et tyrannisk diktatur? Synlig tegn på manglende samtykke? Frihet som ikke-dominering? Irak? (99,9% støtte til Saddam i valg..) Hva kan vi si for Mill’s selvbestemmelsesargument? Er Mill’s selvbestemmelsearg. prudential? Kan et folk frigjøres utenfra?/Kan demokrati pålegges noen? Irak! Frigjøring til hva? Svakhet i Luban’s modell? Jus post bellum fraværende! Mangler realisme? Human security and The Responsibility to Protect Since Luban wrote his article (1980) Bosnia, Kosovo, Rwanda… 9/11..Iraq… Kofi Annan 1999: challenged the member states of the UN to “find common ground in upholding the principles of the Charter, and acting in defence of our common humanity.” “If the collective conscience of humanity … cannot find in the United Nations its greatest tribune, there is a grave danger that it will look elsewhere for peace and for justice.” 2000 (Millennium Report) ”if humanitarian intervention is, indeed, an unacceptable assault on sovereignty, how should we respond to a Rwanda, to a Srebrenica – to gross and systematic violations of human rights that offend every precept of our common humanity? Responses: New concepts, reinterpretations of ’just war’/legalist paradigm in terms of Human Security The Responsibility to Protect (ICISS 2001) (1) Basic Principles A. State sovereignty implies responsibility, and the primary responsibility for the protection of its people lies with the state itself. B. Where a population is suffering serious harm, as a result of internal war, insurgency, repression or state failure, and the state in question is unwilling or unable to halt or avert it, the principle of nonintervention yields to the international responsibility to protect. (2) Foundations The foundations of the responsibility to protect, as a guiding principle for the international community of states, lie in: A. obligations inherent in the concept of sovereignty; B. the responsibility of the Security Council, under Article 24 of the UN Charter, for the maintenance of international peace and security; C. specific legal obligations under human rights and human protection declarations, covenants and treaties, international humanitarian law and national law; D. the developing practice of states, regional organizations and the Security Council itself. (3) Elements The responsibility to protect embraces three specific responsibilities: A. The responsibility to prevent: to address both the root causes and direct causes of internal conflict and other manmade crises putting populations at risk. B. The responsibility to react: to respond to situations of compelling human need with appropriate measures, which may include coercive measures like sanctions and international prosecution, and in extreme cases military intervention. C. The responsibility to rebuild: to provide, particularly after a military intervention, full assistance with recovery, reconstruction and reconciliation, addressing the causes of the harm the intervention was designed to halt or avert. (4) Priorities A. Prevention is the single most important dimension of the responsibility to protect: prevention options should always be exhausted before intervention is contemplated, and more commitment and resources must be devoted to it. B. The exercise of the responsibility to both prevent and react should always involve less intrusive and coercive measures being considered before more coercive and intrusive ones are applied. Principles for Military Intervention (1) The Just Cause Threshold Military intervention for human protection purposes is an exceptional and extraordinary measure. To be warranted, there must be serious and irreparable harm occurring to human beings, or imminently likely to occur, of the following kind: A. large scale loss of life, actual or apprehended, with genocidal intent or not, which is the product either of deliberate state action, or state neglect or inability to act, or a failed state situation; or B. large scale ‘ethnic cleansing’, actual or apprehended, whether carried out by killing, forced expulsion, acts of terror or rape. (2) The Precautionary Principles A. Right intention: The primary purpose of the intervention, whatever other motives intervening states may have, must be to halt or avert human suffering. Right intention is better assured with multilateral operations, clearly supported by regional opinion and the victims concerned. B. Last resort: Military intervention can only be justified when every non-military option for the prevention or peaceful resolution of the crisis has been explored, with reasonable grounds for believing lesser measures would not have succeeded. C. Proportional means: The scale, duration and intensity of the planned military intervention should be the minimum necessary to secure the defined human protection objective. D. Reasonable prospects: There must be a reasonable chance of success in halting or averting the suffering which has justified the intervention, with the consequences of action not likely to be worse than the consequences of inaction. (3) Right Authority (selected) A. There is no better or more appropriate body than the United Nations Security Council to authorize military intervention for human protection purposes. The task is not to find alternatives to the Security Council as a source of authority, but to make the Security Council work better than it has. C.The Security Council should deal promptly with any request for authority to intervene where there are allegations of large scale loss of human life or ethnic cleansing. It should in this context seek adequate verification of facts or conditions on the ground that might support a military intervention. D. The Permanent Five members of the Security Council should agree not to apply their veto power, in matters where their vital state interests are not involved, to obstruct the passage of resolutions authorizing military intervention for human protection purposes for which there is otherwise majority support. - kritisk punkt? A slippery slope? Next time: Will the softening of the legalist paradigm permit military intervention too easily? The quest for a new institutional framework (Buchanan) Interpreting security: the Bush-doctrine Humanitarian intervention: Bosnia and Rwanda (Vetlesen) versus Iraq and Afghanistan (Mellow)