- Still, you've got possibilities, Though you're horribly square

advertisement

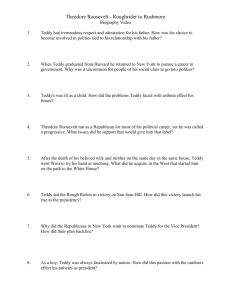

An Adaptation of Teddy by J.D. Salinger Adapted to the stage by Max J. Eber 1 SYNOPSIS American family returning from Europe after visiting doctors and therapists are hounded by a young teacher due to their young son’s peculiar philosophies and seemingly prophetic abilities that have caused a small scandal back in Academic Boston. His pestering culminates one morning when the teacher catches the boy before a swimming lesson, and the unreliable boy divulges on his philosophies. CHARACTERS TEDDY MCARDLE MR. MCARDLE MRS. MCARDLE BOOPER MCARDLE NICHOLSON PURSER CLERK/ENSIGN MATHEWSON NONSPEAKING ROLES MYRON Two to three other cruise line sunbathers. Can be Mr. And Mrs. Mcardle doublecasted with costume change or stage crew. The toddler Myron does not have any lines. TOTAL ACTORS: 7-9 2 ACT ONE SCENE I: CABIN The sound of the ocean can be heard outside. Stage left there are two twin sized beds standing apart and parallel to each other, a nightstand in between. The room is dim, a person lying in each respective bed. On stage right there is a porthole on the wall, white light shining through. On the floor, between the two beds is a pillow and used ashtray. On stage right, TEDDY, a small, underweight boy of ten years of age stands upon a cowhide leather luggage bag to lean through and view out of the porthole. He is wearing an overly washed and starched t-shirt, with a dime sized hole on the right shoulder, extremely dirty white ankle-sneakers without socks, oversized seersucker shorts cinched tight with a black alligator belt. He needs a haircut, his hair outgrown of a former clean-cut style now curling about the nape of his skinny neck. A person in the bed closest to TEDDY, MR. MCARDLE, stirs on lights up. MR. MCARDLE I’ll exquisite day you, buddy, if you don’t get down off that bag this minute. And I mean it. (He kicks off the sheets. MR. MCARDLE is shirtless, wearing only a pajama bottom. He is sunburned, lying rather supine, smoking a cigarette. He flicks the ashes outwards towards the ashtray. He groans.) MR. MCARDLE October, for God’s sake! If this is October weather, gimmie August… (He looks back at TEDDY.) MR. MCARDLE C’mon, what the hell do you think I’m talking for? Get down off there please. (No response. TEDDY sticks his head back out the porthole.) MR. MCARDLE 3 Teddy? Did you hear me?! (Beat. No response.) MR.MCARDLE Teddy. God damn it – did you hear me?! (TEDDY pulls his head back in and turns at the waist, looking at his father innocently as if he had been calling him for the first time.) MR. MCARDLE I want you to get down off that bag, now. How many times do you want me to tell you? (MRS. MCARDLE stirs in the other bed.) MRS. MCARDLE Stay exactly where you are, darling. an inch. Don’t move the tiniest part of (She has whole body covered with sheets and blankets, her body turned towards TEDDY, her back to her husband. She pulls the blankets up closer to her chin. MRS. MCARDLE Jump up and down. Crush Daddy’s bag. MR. MCARDLE That’s a Jesus-brilliant thing to say! I pay twenty-two pounds for a bag and I ask the boy civilly not to stand on it, and you tell him to jump up and down on it. What’s that supposed to be? Funny? (MRS. MCARDLE doesn’t stir or open her eyes.) MRS. MCARDLE If that bag can’t support a ten-year old boy, who’s thirteen pounds underweight for his age, then I don’t want it in my cabin. (MR. MCARDLE takes offense.) MR. MCARDLE You know what I’d like to do? I’d like to kick your goddamn head open. 4 MRS. MCARDLE. Why don’t you? (MR. MCARDLE props himself on his elbow and noticing that the ashtray is on the floor and out of reach and frustrated, squashes out his cigarette on the nightstand’s glass tabletop.) MR. MCARDLE One of these days… MRS. MCARDLE One of these days, you’re going to have a tragic, tragic heart attack. (She clings the covers even closer to her body.) MRS. MCARDLE There will be a small, tasteful funeral, and everybody’s going to ask who that attractive woman in the red dress is, sitting there in the first row, flirting with the organist and making a holyMR. MCARDLE Oh you’re so goddamn funny it isn’t even funny. (He lies down flat again. TEDDY looks back at his parents, withdrawing his head from the porthole and into the cabin.) TEDDY We passed the Queen Mary at three-thirty-two this morning, going the other way if anyone’s interested. (He looks at his parents.) TEDDY (CONT) Which I doubt. That deck steward Booper despises had it on his blackboard. MR. MCARDLE I’ll Queen Mary you, buddy if you don’t get off that bag this minute. Get down from there, now. Go get yourself a haircut or something. (He addresses the back of his wife’s head.) 5 MR. MCARDLE (CONT) He looks precocious, for God’s sake! TEDDY I haven’t any money. I’d like to go journal soon. (He places his hands on the porthole’s sill and rests his chin on them.) TEDDY Mother, you know that man who sits right next to us in the dining room? Not the very thin one. The other one, at the same table. Right next to where our waiter puts his tray down. MRS. MCARDLE Mm-hmm…Teddy. Darling. Let Mother sleep just five minutes more, like a sweet boy. (TEDDY interrupts but doesn’t move his chin up from up resting on his hands and looking outside at the ocean.) TEDDY Wait just a second, this is interesting! He was in the gym a little while ago, while Sven was weighing me. He came up and started talking to me. He heard that last tape I made. Not the one in April. The one in May. He was at a party in Boston just before he went to Europe and somebody at the party knew somebody in the Leidekker examining grouphe didn’t say who- and they borrowed that last tape - I made and played it at the party. He seems very interested in it. He’s a friend of Professor Babcock’s. Apparently he’s a teacher himself. He said he was at Trinity College in Dublin, all summer. (MRS. MCARDLE opens her eyes and looks over at TEDDY wearily.) MRS. MCARDLE Oh? At a party they played it? TEDDY I guess so, he told Sven quite a bit about me, right while I was standing there. It was rather embarrassing. 6 MR. MCARDLE Why should it be embarrassing? (TEDDY hesitates.) TEDDY I said ‘rather’ embarrassing. I qualified it. MR. MCARDLE I’ll qualify you, buddy, if you don’t get the hell off that bag. (He sits up and lights a second cigarette.) MR. MCARDLE I’m going to count three. One, God damn it…Two… (MRS. MCARDLE suddenly stirs a bit.) MRS. MCARDLE What time is it? Don’t you and Booper have a swimming lesson at tenthirty? TEDDY We have time…OOH! (He thrusts his head out of the porthole, keeps it there for a few seconds and then draws it back in. He reports to his parents;) TEDDY Someone just dumped a whole garbage can of orange peels out the window. MR. MCARDLE Out the window. Out the window. (He flicks out his ashes.) MR. MCARDLE Out the porthole, buddy, out the porthole. (He looks over at the back of his wife’s head again. TEDDY looks back out the porthole.) 7 MR. MCARDLE Call Boston. Quick, get the Leidekker examining group on the phone. MRS. MCARDLE Oh, you’re such a brilliant wit, Why do you try? (TEDDY withdraws his head completely from the porthole. TEDDY They float very nicely. That’s interesting. MR. MCARDLE Teddy. For the last time. I’m going to count three, and then I’mTEDDY I don’t mean it’s interesting that they float, it’s interesting that I know about them being there. If I hadn’t seen them, then I wouldn’t know they were there, and if I didn’t know they were there, I wouldn’t be able to say that they even exist. That’s very nice, perfect example of the wayMRS. MCARDLE Teddy! Go find Booper for me. Where is she? I don’t want her lolling around in that sun again today, with that burn. TEDDY She’s adequately covered. I made her wear her dungarees. (He looks outside the porthole again.) TEDDY Some of them are starting to sink now. In a few minutes, the only place they’ll still be floating will be inside my mind. That’s quite interesting, because if you look at it a certain way, that’s where they started floating in the first place. If I’d never been standing here at all, or if somebody’d come along and sort chopped my head off right while I wasMRS. MCARDLE WHERE is she now? Look at Mother a minute, Teddy. 8 (TEDDY turns around and looks at his mother.) TEDDY What? MRS. MCARDLE Where’s Booper now? I don’t want her meandering all around the deck chairs again, bothering people. If that awful manTEDDY She’s all right. I gave her the camera. (MR. MCARDLE lurches up in bed on one arm, alarmed.) MR. MCARDLE You gave her camera! What’s the hell’s idea? My goddam Leica! I’m not going to have a six-year-old child gallivanting all overTEDDY I showed her how to hold it so she won’t drop it, and I took the film out, naturally. She’s quite a capable… MR. MCARDLE I want the camera, Teddy. You hear me!? I want you to get down off that Gladstone this minute, and I want that camera back in this room in five minutes- or there’s going to be one little genius among the missing. Is that clear? (TEED turns around on the bag completely and then jumps down. He bends down and starts to tie his laces on his tennis shoe.) MRS. MCARDLE Tell Booper I want her. And come give Mother a kiss. (TEDDY finishes his sneaker lace, and gives his mother a pefunct kiss on the cheek. She tries to hold TEDDY, but he has already pulled away. He goes in between his parent’s beds, picks up his father’s pillow and places it underneath his arm as he then picks up the ashtray. He transfers the ashtray to his other hand and brushes his father’s cigarette ashes from the nightstand into the ashtray with the edge of the hand. He then wipes the entire nightstand with his forearm, to remove the filmy wake of leftover 9 ash. He looks at his forearm and wipes it on his shorts. He then, ceremoniously, places the ashtray dead center on the nightstand. His father, agitated, stops watching him and looks away. TEDDY Don’t you want your pillow? MR. MCARDLE I want that camera young man. TEDDY You can’t possibly be very comfortable in that position. It isn’t possible. (He places the pillow at the foot of his father’s bed.) TEDDY I’ll leave this right here. MRS. MCARDLE Teddy, Tell Booper I want to see her before her swimming lesson. MR. MCARDLE Why don’t you leave the kid alone? You seem to resent her having a few lousy minutes’ freedom. You know how to you treat her? I’ll tell you exactly how you treat her, You treat her like a bloomin’ criminal. MRS. MCARDLE Bloomin’! Oh that’s cute! You’re getting so English, lover. (TEDDY lingers at the door, fidgeting with the door handle, turning it slowly back and forth.) TEDDY She’s afraid of her, that’s why. (TEDDY sighs.) TEDDY You know, after I go out this door, I may only exist in the minds of all my acquaintances. I may be just an orange peel… 10 MRS. MCARDLE What, darling? MR. MCARDLE Let’s get on the ball, buddy. Let’s get that Leica down here. MRS.MCARDLE No, no, come give Mother a kiss. A nice big one. TEDDY seems absent. TEDDY Not right now. I’m tired… (He pauses and looks at his parents. He exits and closes the door behind him. BLACKOUT 11 ACT ONE SCENE II: LIGHT’S UP OCEAN LINER DECK (TEDDY walks out along the main deck, reading the ship’s newspaper pamphlet he picks up from a stand. Before him in center stage there is a counter, the Purser’s desk, with another young attractive woman in a naval uniform. She is stapling pieces of paper together. TEDDY walks up to the counter. TEDDY Can you tell me what time that game starts today, please? PURSER CLERK I beg your pardon? TEDDY Can you tell me what time that game starts today? (She smiles.) PURSER CLERK What game honey? TEDDY You know. That word game they had yesterday and the day before, where you’re supposed to supply the missing words. It’s mostly you have to put everything into context. (The girl goes to staple another stack of papers but then refrains and withdraws her hand from the stapler.) PURSER CLERK Oh…not till late afternoon, I believe. It’s around four o’clock. Isn’t that a little over your head dear? TEDDY No it isn’t…you underestimate me. Thank you. (TEDDY starts to leave.) PURSER CLERK Wait a minute, honey! What’s your name? 12 (TEDDY turns around.) TEDDY Theodore McArdle. What’s yours? PURSER CLERK My name? (She smiles.) PURSER CLERK My name’s Ensign Mathewson. (She finally presses down on the stapler as Teddy watches.) TEDDY I knew you were an ensign. I’m not sure, but I believe when somebody asks your name you’re supposed to say your whole name. Jane Mathewson, or Phyillis Mathewson, or whatever the case may be. (ENSIGN MATHEWSON grips the stapler.) ENSIGN MATHEWSON Oh really? TEDDY As I say, I think so. I’m not sure, though. It may be different if you’re in uniform. Anyway, I may not be able to play after all if it’s at that time this afternoon. Thank you for the information. Goodbye! (He turns and walks on. ENSIGN MATHEWSON looks befuddled and snippily staples another packet of papers as TEDDY walks out onto the the adjoining Sports Deck. BOOPER, TEDDY’S six year old sister with blonde hair stands on stage right with a small two to three year old boy, MYRON, standing by her, observing. She is squatting, overseeing two stacks of twelve to fourteen shuffleboard discs stacked neatly into color coordinated stacks of red and black. She notices as TEDDY approaches.) BOOPER Look! (She seems to command her brother to look at her two stacks. She surrounds the two stacks with her arms, as if to frame them. She 13 looks over to MYRON beside her and then incredibly hostile, says;) BOOPER Myron! You’re making it all shadowy, so my brother can’t see. Move your carcass! (She shuts her eyes and haughtily waits until the young boy moves back. TEDDY walks up to the two stacks.) TEDDY That’s very nice, very symmetrical. (BOOPER looks viciously back over to MYRON.) BOOPER This guy, never even heard of backgammon. They don’t even have a board! (TEDDY looks objectively over at MYRON, who looks back at TEDDY rather innocuously.) TEDDY Listen…I’d like to go journal as soon as I can… (He turns back to BOOPER.) TEDDY Booper, where’s the camera? Daddy wants it right away… (BOOPER doesn’t seem to listen, she carries on.) BOOPER He doesn’t even live in New York… (She gets up in his face.) BOOPER And his father’s dead. He was killed in Korea! (She turns back to MYRON.) BOOPER WASN’T HE? 14 (She doesn’t wait for a response.) BOOPER (CONT) Now if his mother dies, he’ll be an orphan! He didn’t even know that! (She looks back to MYRON.) BOOPER (CONT) Did you?! (MYRON folds his arms, noncommittal. BOOPER becomes even more shrieking.) BOOPER You’re the stupidest person I ever met! You’re the stupidest person in this ocean. DID YOU KNOW THAT? TEDDY He is not. (TEDDY looks at MYRON.) TEDDY You are not, Myron. (He grabs BOOPER’S shoulders and pulling her away from MYRON holds her still.) TEDDY Give me your attention a second. Where’s the camera? I have to have it immediately. Where is it? (BOOPER flails her arm in no particular direction.) BOOPER Over there… (She pulls away from TEDDY and kneels down and draws her two stacks of shuffleboard discs in closer to her.) BOOPER All I need now are two giants. I could summon up two giants and they could play backgammon till they got all tired and then they could 15 climb up on that smokestack up there and throw these at everybody and kill them! (She looks at MYRON, almost sadistic.) BOOPER They could kill your mother. And if that didn’t kill her, you know what you could do? You could put some poison on some marshmallows and make her eat it! (TEDDY spots the Leica camera nearby away against the railing in the drain gully. He walks over and picks it up, places the strap around his neck. He pauses, then removes it and then walks over to BOOPER and holds it out to her. TEDDY Booper, do me a favor. You take it down, please. It’s ten o’clock. I have to write in my diary. (The girl responds in an overtly girly tone.) BOOPER I’m busy. TEDDY Mother wants to see you right away. (BOOPER quickly looks over to TEDDY, enraged.) BOOPER You’re a liar! TEDDY I’m not a liar. She does. So please, take this down when you go..c’mon, Booper, Pavarti… (He tries to give her the camera. She stays hunched over her two stacks. BOOPER DON’T CALL ME THAT! WHY DO YOU ALWAYS CALL ME THAT?! Besides…what’s she want me for? I don’t want to see her. 16 (MYRON slowly tries to take a shuffleboard disk from the red stack. BOOPER suddenly strikes his hand.) BOOPER Hands off! (TEDDY places the camera strap around her neck.) TEDDY I’m serious, now. Take this down to Daddy, right away, and then I’ll see you at the pool later on. I’ll meet you right at the pool changing room at ten-thirty. Be on time, now. Leave yourself plenty of time to get there. (He turns and starts to leave, stage left. BOOPER starts to scream after him.) BOOPER I HATE YOU! I HATE EVERYBODY IN THIS OCEAN! (She kicks her two stacks, scattering the shuffleboard chips which frighten MYRON, who dashes away. She wretches the camera off her neck and throws it onto the ground hard in front of her, then stomps away, swiping up the strap as she passes, and, fake crying, drags it, now broken, behind her.) BLACKOUT 17 ACT ONE SCENE III: SUN DECK Lights up on the Sun Deck, a long stretch of flat space devoted to three lines thick of white lounge chairs, some occupied by sunbathers, who either splay out completely prostrate or lean back in the chairs in a higher, more upwards angle to read. On stage left there is an entrance to a stairwell going down with a sign with a large red arrow that reads ENTRANCE TO POOL. The sports deck can be seen above the Sun deck, a set of railed stairs extends down across from stage right to stage left connecting the two levels, the stairs ending right at stage left at the entrance to the to the pool. (TEDDY, now wearing a pair of large wayfarer sunglasses and carrying what looks like a cheap notebook, enters stage left and explores the lines of chairs, reading the name placards on the empty chairs that reserve them for certain guests. He comes across his families four cushioned chairs on the middle row, stage right and sits down in an chair. He props up the notebook on his thigh and opens it. He reads out loud :) TEDDY Last entry, Diary for October 27th, 1952. Property of Theodore McArdle, 412 A Deck. Appropriate and pleasant reward if finder promptly returns to Theodore McArdle if found. Note; See if you can find daddy’s army dog tags and wear them whenever possible. It won’t kill you and he will like it. Answer Professor Mandell’s letter. Ask him not to send me any more poetry books, I am quite sick of them, though do not make that apparent. (He seems to make an edit with a ballpoint pen he withdraws from his pocket. He sighs.) TEDDY (CONT) A man walks along the beach and unfortunately gets hit in the head by a coconut. His head unfortunately cracks open in two halves. Then his wife comes along the beach singing a song and sees the two halves and recognizes them and picks them up. She gets very sad of course and 18 cries heart-breakingly. That is exactly where I am tired of poetry. Supposing the lady just picks up the two halves and shouts into them very angrily “Stop that!” Do not mention this when you answer his letter, however. It is quite controversial and Mrs. Mandell is a poet besides. (He turns the page.) TEDDY Note; Get Sven’s address in Elixabeth, New Jersey. It would be interesting to meet his wife, also his dog Lindy. However, I would not like to own a dog myself. Pomeranians especially are not to be trusted much, especially Miss Adgerton’s, the nasty… (He makes an edit.) TEDDY Insufferable little thing. (He keeps reviewing his previous entry. He scratches something out. The legs and shoes of a man wearing charcoal grey trousers appear stage left on the Sun Deck level.) TEDDY. Words and expressions to look up in the library tomorrow when you return the books- nephritis, myriad, gift horse, cunning, triumvirate. Be nice to the librarian. Discuss some general things with him when he gets…kittenish. (He then starts to write full force, speaking what he writes as he goes.) TEDDY Diary for October 28th, 1952. Same address and reward as written on October 26th and 27th, 1952. Note; I wrote letters to the following person after meditation this morning; Dr. Wokawara, Professor Mandell, Professor Peet, Burgess Hake, Jr., Roberta Hake, Sandord Hake, Grandma Hake, Mr. Graham, and Professor Walton. I could have asked mother where daddy’s dog tags are but she would probably say I don’t have to wear them. I know he has them with him because I saw him pack them. (He pauses.) 19 TEDDY(CONT) Life is a gift horse in my opinion. I think it is very tasteless of Professor Walton to criticize my parents. He wants people to be a certain way. He pauses…Booper has certainly forgotten her time as a goddess, being part of God. She does not realize who she is. Mother has said it was very wicked of me to say that but she is who she is, I have seen her truer form after all. (He sighs again.) TEDDY It will either happen today or February 14th, 1958, when I am sixteen. It is ridiculous to mention even. But, it’s probably inevitable… TEDDY sits, poised, ceasing to stop writing but keeps his pen in place upon the paper as if waiting for more. He looks disturbed. The pair of legs walk down to the stairs and descend, exposing as it descends NICHOLSON a young man in his mid-twenties to thirties, wearing button down shirt with no necktie and a well-aged if not slightly ugly Ivy League type of herringbone jacket. A few people look up at him for disturbing their sun. He gets down onto the Sundeck and moseys over and then stops in front of TEDDY, who does not notice. He places one hand in his pocket and genially says;) NICHOLSON Hello, there! (TEDDY is knocked out of his little trance and looks up at the man, all the while shutting his notebook from view.) TEDDY Oh you, from the gym…what do you want? NICHOLSON Mind if I sit down a minute? (He signals to one of the McArdle’s chairs.) NICHOLSON This anybody’s chair? 20 TEDDY Well these chairs belong to my family, but my parents aren’t up yet. NICHOLSON Not up? On a day like this? (He lowers himself into the chair anyway next to TEDDY, who doesn’t seem too amused by the gesture.) NICHOLSON That’s sacrilege, absolute sacrilege. (He stretches out. He is not fat but it becomes apparent he has large legs. Not athletic. He holds up a hand to his face, like a visor over his eyes as he squints into the sun.) NICHOLSON Oh, God, what a great day, I’m an absolute pawn when it comes to the weather. (He crosses his legs.) NICHOLSON As a matter of fact, I’ve been known to take a perfectly normal rainy day as a personal insult, so this is absolute manna to me. (He looks down to TEDDY, who has been staring forewords, rather stoic.) NICHOLSON How are you and the weather? The weather ever bother you out of all sensible proportion? TEDDY I don’t take it too personal, if that’s what you mean. It is splendid though. (NICHOLSON gives a deep laugh.) NICHOLSON Wonderful! (He leans back forward.) 21 NICHOLSON My name, incidentally, is BOB NICHOLSON. I don’t know if we quite got around to that in the gym. I know your name, of course. (TEDDY shifts his weight and puts away the small notebook into his shorts.) NICHOLSON I was watching you write from up there, Good Lord you were working away like a little Trojan. TEDDY I was writing something in my notebook. It’s very important, in case I ever leave it behind. (NICHOLSON nods.) NICHOLSON How was Europe? Did you enjoy it. TEDDY Yes, very much, thank you. NICHOLSON Where did you all go? (TEDDY scratches the calf of his leg.) TEDDY Well, it would take me too much time to name all the places, because we took our car and drove fairly great distances. My mother and I were mostly in Edinburgh, Scotland, and Oxford, England, though. I think I told you in the gym I had to be interviewed at both those places. Mostly the University of Edinburgh. NICHOLSON No I don’t believe you did. I was wondering if you’d done anything like that. How’d it go? Did they grill you? TEDDY I beg your pardon? 22 NICHOLSON I mean, how’d it go? Was it interesting? TEDDY At times, yes. At times, no. We stayed a bit too long. My father wanted to get back to New York a little sooner than this ship. But some people were coming over from Stockholm, Sweden and Innsbruck, Austria, to meet me, and we had to wait around. NICOLSON It’s always that way. TEDDY looks at NICHOLSON truly directly for the first time. He takes off his sunglasses.) TEDDY Are you a poet? NICHOLSON A poet? Lord, no. Alas, no. Why do you ask? TEDDY I don’t know. Poets are always taking the weather so personally. They’re always sticking their emotions in things that have no emotions. NICHOLSON smiles and reaching into his jacket pulls out cigarettes and matches.) NICHOLSON I rather thought that was their stock in trade. Aren’t emotions what poets are primarily concerned with? (TEDDY is not paying attention, gazing off. NICHOLSON lights his cigarette and leans back.) NICHOLSON I understand you left a pretty disturbed bunchTEDDY Nothing in the voice of the cicada intimates how soon it will die, along this road goes no one, this autumn eve. 23 NICHOLSON What was that? He smiles. NICHOLSON Say it again. TEDDY Those are Japanese poems. They’re not full of emotional stuff. (TEDDY leans up and gives his right ear a clap with his hand.) TEDDY I still have some water in my ear from my swimming lesson yesterday, excuse me it’s started to bother me. (He gives his ear a few more claps and leans back into the chair, looking smaller than ever.) NICHOLSON I understand you left a pretty disturbed bunch of After that last little set-to. The whole Leidekker more or less, the way I understand it. I believe I rather a long chat with Al Babcock last June. Same of fact, I heard your tape played off. pedants up at Boston. examining group, told you I had night, as a matter TEDDY Yes you did, you told me. NICHOLSON I understand they were a pretty disturbed bunch, from what Al told me, you all had quite a little lethal bull session late one night- the same night you made that tape, I believe. (He takes a drag from his cigarette.) NICHOLSON From what I gather, you made some little predictions that disturbed the boys to no end. Is that right? 24 TEDDY I wish I knew why people think it’s so important to be emotional. My mother and father don’t think a person’s human unless he thinks a lot of things are very sad or very annoying or very-very unjust, sort of. My father gets very emotional even when he reads the newspaper. He thinks I’m inhuman. (NICHOLSON flicks away his cigarette.) NICHOLSON I take it you have no emotions? (TEDDY pauses, reflecting.) TEDDY If I do, I don’t remember when I ever used them, I don’t see what they’re good for. NICHOLSON You love God don’t you? Isn’t that your forte, so to speak? From what I heard on that tape and from Al Babcock you know quite a lotTEDDY Yes, sure I love Him. But I don’t love Him sentimentally. He never said anybody had to love Him sentimentally. If I were God, I certainly wouldn’t want people to love me sentimentally. It’s too unreliable. NICHOLSON You love your parents, don’t you? TEDDY Yes, I do-very much. But you want to make me use that word to mean what you want it to mean- I can tell. NICHOLSON All right. In what sense do you want to use it? (TEDDY thinks.) TEDDY You know what the word ‘affinity’ means? 25 NICHOLSON I have a rough idea. TEDDY I have a very strong affinity for them. They’re my parents, I mean, and we’re all part of each other’s harmony and everything. I want them to have a nice time while they’re alive, because they like having a nice time…but they don’t love me and Booper- that’s my sister- that way. I mean they don’t seem able to love us just the way we are. They don’t seem able to love us unless they can keep changing us a little bit. They love their reasons for loving us almost as much as they love us, and most of the time more. It’s not so good, that way. (He leans over to NICHOLSON.) TEDDY Do you have the time, please? I have a swimming lesson at ten-thirty. NICHOLSON You have time. (He pushes back his cuff to look at his wristwatch.) NICHOLSON It’s just ten after ten. TEDDY Thank you. (He sits back into the chair.) TEDDY We can enjoy our conversation for a few more minutes. (NICHOLSON notices his cigarette end and puts it out with his shoe.) NICHOLSON As I understand it, you hold pretty firmly to the Vedantic theory of reincarnation. 26 TEDDY It isn’t a theory, it’s as much a partNICHOLSON All right. All right.. (He holds up his hands as if in surrender.) NICHOLSON We won’t argue that point, for the moment. Let me finish. (He crosses his legs again.) NICHOLSON From what I gather, you’ve acquired certain information, through meditation, that’s given you some conviction that in your last incarnation you were a holy man in India, but more or less fell from Grace. TEDDY I wasn’t a holy man, I was just a person making very nice spiritual advancement, that’s all. There’s a difference. NICHOLSON All right- whatever it was, but the point is you feel that in your last incarnation you more or less fell from Grace before final Illumination. Is that right, or am ITEDDY That’s right. I met a lady and I sort of…stopped meditating. (He takes his hands off the arm rests of the chair and puts them under his thighs.) TEDDY I would have had to take another body and come back to earth again anyway- I mean I wasn’t so spiritually advanced that I could have died, if I hadn’t met that lady, and then gone straight to Brahma and never again have to come back to earth. But I wouldn’t have had to get incarnated in an American body if I hadn’t met that lady. I mean it’s very hard to meditate and live a spiritual life in America. People think you’re a freak if you try to. My father thinks I’m a freak, in a 27 way. And my mother- well she doesn’t think it’s good for me to think about God all the time. She thinks it’s bad for my health. (NICHOLSON looks at him, studying him.) NICHOLSON I believe you said on that last tape that you were six when you first had a mystical experience. Is that right? TEDDY I was six when I saw that everything was God, and my hair stood up and all that. It was on a Sunday, I remember. My sister was only a very tiny child then, and she was drinking her milk, and all of the sudden I saw that she was God and the milk was God. Chaos and Order swirling and entering, exiting, everything about her was Pavarti, and Durga and Kali, all separate, all equal. I mean, all she was doing was pouring God into God, if you know what I mean. (NICHOLSON doesn’t say anything.) TEDDY But I could get out of the finite dimensions fairly often when I was four. Not continuously or anything, but fairly often. (NICHOLSON nodded.) NICHOLSON You did? You could? TEDDY Yes, that was on the tape…or maybe it was the on the one I made last April. I’m not sure. (NICHOLSON takes out his cigarettes again but keeps his eyes on TEDDY.) NICHOLSON How does one get out of the finite dimensions? (He laughs.) NICHOLSON (CONT) I mean, to begin very basically, a block of wood is a block of wood, for example. It has length, width28 TEDDY It hasn’t! That’s where you’re wrong. Everybody just thinks things keep stopping off somewhere. They don’t! That’s what I was trying to tell Professor Peet. (TEDDY shifts in his seat, takes out an ugly handkerchief and blows his nose.) TEDDY (CONT) The reason things seem to stop off somewhere is because that’s the only way most people know how to look at things. But that doesn’t mean they do. It’ like my parents looking at my sister and not understanding her power. Would you like to hold up your hand a second, please? NICHOLSON My arm? Why? TEDDY Just do it. Just do it a second. (NICHOLSON raises his forearm an inch or two above the level of the armrest.) NICHOLSON This one? (TEDDY nods.) TEDDY What do you call that? NICHOLSON What do you mean? It’s my arm. It’s an arm. TEDDY How do you know it is? You know it’s called an arm, but how do you know it is one? Do you have any proof that it’s an arm? 29 NICHOLSON I think that smacks of the worst kind of sophistry, kid, frankly it does. It’s an arm. We call it an arm. It has to have a name to distinguish it from other objects. I mean, you can’t simplyTEDDY You’re just being logical. NICHOLSON I’m just being what? TEDDY Logical. You’re just giving me a regular, intelligent answer; I was trying to help you. You asked me how I get out of the finite dimensions I feel like it. I certainly don’t use logic! Logic’s the first thing you have to get rid of! (NICHOLSON looks sour.) TEDDY Do you know Adam? NICHOLSON Do I know who? TEDDY Adam. In the Bible. NICHOLSON Not personally. (TEDDY hesitates.) TEDDY Don’t be angry with me. You asked me a question and I(NICHOLSON shouts a bit too loudly.) 30 NICHOLSON I’m not angry with you, for heaven’s sake! (A few sunbathers look over at Nicholson, who seems rather agitated. A sunbather turns on a portable radio. A jazzy, orchestral tune now plays softly in the background.) TEDDY Okay. You know that apple Adam ate in the Garden of Eden? You what was in that apple? Logic! Logic and intellectual stuff, That’s what was in it. So-this is my point- what you have to do is vomit it up if you want to see things as they really are. I mean if you vomit it up, then you won’t have any more trouble with blocks of wood and stuff. You won’t see everything stopping off all the time. And you’ll know what your arms really is, if you’re interested! Do you know I mean? Do you follow me? NICHOLSON I follow you. TEDDY The trouble is, most They don’t even want just want new bodies with God, where it’s people don’t want to see things the way they are. to stop getting born and dying all the time. They all the time, instead of stopping and staying really nice. (ENSIGN MATHEWSON passes with a large stack of papers.) TEDDY I never saw such a bunch of apple eaters. (He shakes his head. BOOPER, in a one piece bathing suit with an unfortunate pattern, a towel on her shoulder walks down across the Sun Deck and to the entrance to the stairs to the pool. TEDDY and NICHOLSON look over, BOOPER catches sight of TEDDY. She tense up and, gives out an aggravated groan, and then stomps her way down the stairs flippantly. NICOLSON looks over to TEDDY. TEDDY My sister…she’s a bit early. 31 NICHOLSON If you’d rather not discuss this, you don’t have to. But it is true, or isn’t it, that you informed the whole Leidekker examining bunchWalton, Peet, Larsen, Samuels, and that bunch- when and where and how they would eventually die? Is that true or isn’t it? The rumor around Boston. (Beat.) TEDDY No. It’s isn’t true. ( NICHOLSON looks distraught.) TEDDY I told them places, and times, when they should be very, very careful. And I told them certain things it might for them to do…but I didn’t say anything like that. I didn’t say anything was inevitable, that way. Anything can happen. And I didn’t tell Professor Peet anything like that at all. Firstly, he wasn’t one of the ones who were kidding around asking me a bunch of questions. I mean all I told Professor Peet was that he shouldn’t be a teacher anymore after January- that’s all I told him. (He pauses.) TEDDY All those other professors, they practically forced me to tell them all that stuff. It was after we were all finished with the interview and making that tape, and it was quite late and they all kept sitting around smoking cigarettes and getting very kittenish. NICHOLSON But you didn’t tell Walton, Larsen, for example when or how they would eventually die? TEDDY No. I did not. I wouldn’t have told them any of that stuff, but they kept talking about it. Professor Walton sort of started it. He said he really wished he knew when he was going to die, because then he’d know what work he should do and what work he shouldn’t do, and how to use his time to his best advantage, and all like that. And they all said that…so I told them a little bit. I didn’t tell them when they were 32 actually going to die, though. That’s a very false rumor. I could have, but I knew that in their hearts they really didn’t want to know. I mean I knew that even though they teach Religion and Philosophy and all, they’re still pretty afraid to die. (They sit in silence. Beat.) TEDDY It’s so silly, all you do is get the heck out of your body when you die. My gosh, everybody’s done it thousands and thousands of times. Just because they don’t remember it doesn’t mean they haven’t done it. Or because you don’t see it something happens. It’s so silly. NICHOLSON That may be. But the logical fact remains that no matter how intelligentlyTEDDY It’s so silly! For example, I have a swimming lesson, as you know, in about five minutes. I could go downstairs to the pool, and there might not be any water in it at all. This might be the day they actually change the water or something. A child had an “accident” in the water. What might happen, though, I might walk up to the edge of it, just to have a look at the bottom, for instance, and my sister might come up and sort of push me in. I could fracture my skull and die instantaneously. Then Kali could finally appear and lap up all the blood. Then again, I could push her into a pool, and it could be absolutely full. I could trip in on my own accord. There are those possibilities as well. There are infinite possibilities as to what can happen really, just as there are infinite ways to evoke and reach a sleeping God. (He looks at NICHOLSON.) TEDDY Any of those could happen. My sister’s only six, and she hasn’t been a human being for very many lives, and she doesn’t like me very much nor do our parents know how to handle her either. They likewise don’t know how to handle me. (He pauses.) TEDDY It’s a rather fractured affair. 33 (He pauses, looking genuinely, for the first time, a genuinely sad and lonely boy, and most importantly the possibility of a fraudulent liar.) TEDDY I mean, what would be tragic about it all though, if I was to die? What’s there to be afraid of, I mean? I’d just be doing what I was supposed to do, that’s all, wouldn’t I? NICHOLSON It might not be a tragedy from your point of view, but what about for mother and dad? Ever consider that? TEDDY Yes of course, I have. But that’s only because they have names and emotions for everything that happens. You know Sven, the man that takes care of the gym? (NICHOLSON nods.) TEDDY Well, if Sven dreamed tonight that his dog died, he’d have a very, very bad night’s sleep, because he’s very fond of his dog. But when he woke up in the morning, everything would be all right. He’d know it was all a dream and he could be at peace. NICHOLSON What’s your point kid? TEDDY The point is if his dog really died, it would be exactly the same thing. Only, he wouldn’t know it. I mean he wouldn’t wake up until he died himself. The loss wouldn’t leave. (NICHOLSON, rather detached, massages the back of his neck. The sunlight becomes really bright, as if coming out from behind a veil of clouds. TEDDY stands up. TEDDY I really have to go now, I’m afraid. I have a few minutes and I need to go change for my swimming lesson in the changing room before I’m too late. 34 (NICHOLSON stands up, a bit bit panicked to the idea of TEDDY leaving. He gestures out as if to stop TEDDY.) NICHOLSON Can I, May I ask why you told Professor Peet he should stop teaching after the first of the year? I know Bob Peet. That’s why I ask. (TEDDY sits on the edge of his chair again.) TEDDY Oh, only because he’s quite spiritual, and he’s teaching a lot of stuff right now that isn’t very good for him if he wants to make any real spiritual advancement. It’s time for him to take everything out of his head, instead of putting more stuff in. He could get rid of a lot of the apple in just this one life if he wanted to. He’s very good at meditating. (TEDDY stands up and again.) TEDDY I better go now…I don’t want to be too late. I have to see how the lesson will be going today. (NICHOLSON looks at him pleadingly, holding onto his arm not to go. The sunlight gets even brighter.) NICHOLSON What would you do if you could change the educational system? Ever think of that at all? TEDDY I really have to go. We might do butterfly stroke. He struggles against NICHOLSON’s hold. NICHOLSON almost seems childlike. He pleads.) NICHOLSON Just answer that one question! Education’s my baby, actually, that’s what I teach. That’s why I ask! TEDDY Well…I’m not sure what I’d do, I know I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t start with the things schools usually start with. 35 TEDDY I’d probably show all the children how to meditate, I’d try to show them how to find who they are, not just what their names are and things like that..I guess even before that, I’d get them to empty out everything their parents and everybody ever told them. I mean even if their parents told them an elephant’s big, I’d make them empty that out. An elephant’s only big when it’s next to something else, a dog, or a lady with a funny hat, for example. I wouldn’t even tell them what an elephant has a trunk. I might show them an elephant, if I had one handy, but I’d let them just walk up to the elephant not knowing anything more about it than the elephant knew them. The same thing with grass and other things. I wouldn’t tell them grass is green! Colors are only names. I mean if you tell them the grass is green, it makes them start expecting the grass to look a certain way… I don’t know I’d make them vomit up every bit of the apple their parents and everybody made them take a bite out of. (NICHOLSON gets agitated again.) NICHOLSON There’s no risk you’d be raising a little generation of ignoramuses? (The same woman who had looked over at him from her sunning spot, looks over, bothered. NICHOLSON, catching sight, lets go of Teddy’s arm.) TEDDY Why? They wouldn’t be any more be ignoramuses than an elephant is. Or a bird. Or a tree. Just because something is a certain way, instead of just behaves a certain way, doesn’t mean it’s an ignoramus. NICHOLSON No? TEDDY No! Besides if they wanted to learn things, all that other stuff, they could do it, later on when they were older, if they wanted. But I’d want them to begin with all the real ways of looking at things not just the way all the other apple-eaters look at things. I really have 36 to go now, I have to see what will happen in our lesson today. Honestly, I’ve enjoyedNICHOLSON Just, one second! (He touches Teddy’s arm again. TEDDY tries to draw away.) NICHOLSON (CONT) Please sit down a minute. Ever think you might like to do something in research when you grow up? Medical research, or something of that kind? It seems to me, with your mind you might eventuallyTEDDY I thought about that once, a couple of years ago, I’ve talked with quite a few doctors. (He shakes his head.) TEDDY That wouldn’t interest me much. Doctors stay too right on the surface. They’re always talking cells and things. NICHOLSON Oh? You don’t attach any importance to cell structure? TEDDY Yes, sure I do. But doctors talk about cells as if they had such unlimited importance by themselves. As if they didn’t really belong to a person that has them. (TEDDY messes with his hair and pushes it off his forehead.) TEDDY I grew my own body. Nobody else did it for me. So if I grew it, I must have known how to grow it. Unconsciously at least. I may have lost the conscious knowledge of how to grow it sometimes in the last hundred thousand years, but the knowledge is still there, because obviously, I’ve used it. I would take quite a lot of emptying out to get the whole thing back- I mean the conscious knowledge but you could do it if you wanted to. If you opened up wide enough, and stuff like that. 37 TEDDY picks up NICHOLSON’S hand and shakes it, once, cordially. TEDDY Goodbye. I have to go. I might have to correct myself, we might do the breaststroke after all. I’d like to know what we’re doing beforehand and I need to change, and well, I’m going to be late…so, again. Goodbye. (The sunlight reaches its brightest. TEDDY leaves and walks through the chairs and to the stairwell down to the pool and out of sight. NICHOLSON sits, holding his hand up to the sun. He sits and, distressed, lights and smokes a cigarette in silence. The music of the sunbather’s radio playing in the background. He then looks over in the direction of the stairwell down to the pool. He snuffs out his cigarette and, almost in a panic sits up and walks, weaving in and out of the chairs of sunbathers again, towards the stairwell. As he approaches the opening, an all piercing, scream, from a small, female child can be heard, highly acoustical, as if reverberating within four tiled walls. NICHOLSON runs down the staircase. 38