Wake Forest-Manchester-Shaw-Neg-Kentucky

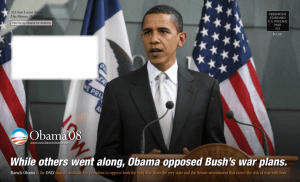

advertisement