Kansas-Khatri-Schile-Neg-UMKC-Round5

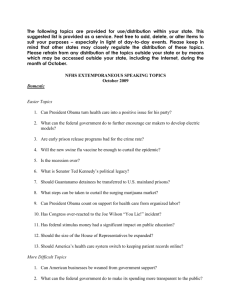

advertisement