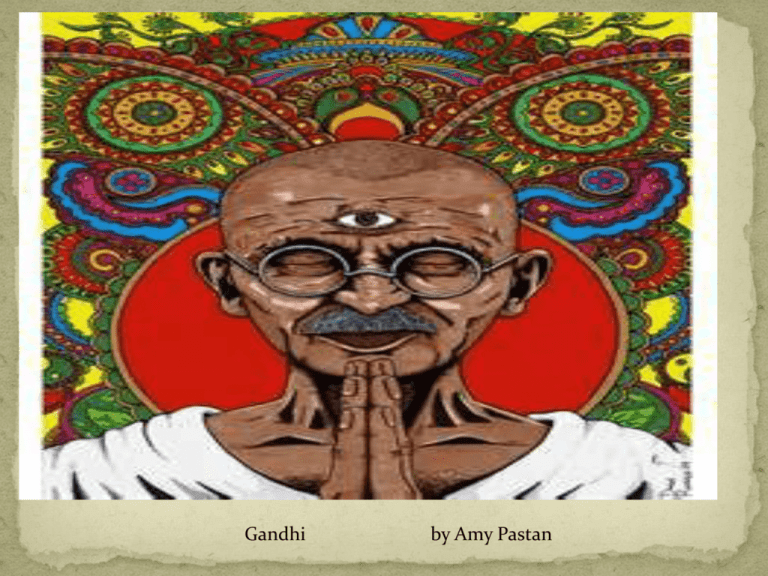

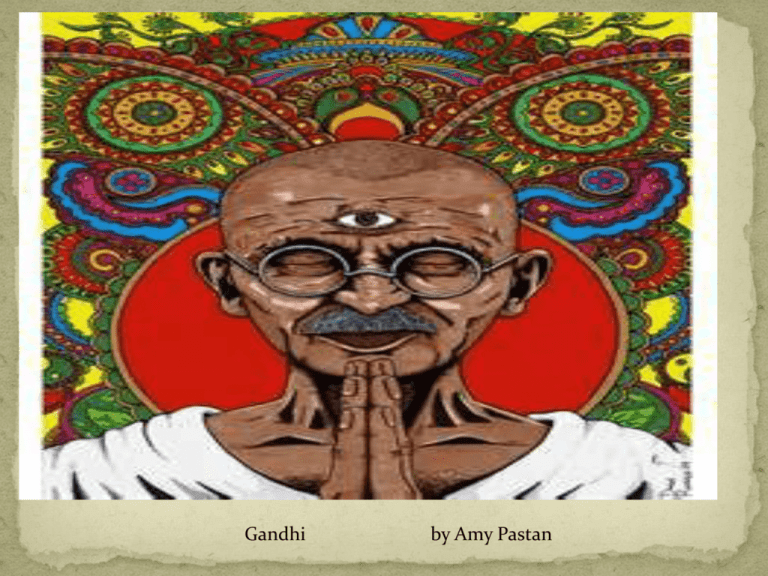

Amy Pastan

Gandhi

by Amy Pastan

Gandhi is a nonfiction, informational book subtitled

“A Photographic Story of a Life”. It is an illustrated

biography.

Gandhi is basically organized in chronological order,

but begins with a brief introduction to India in the late

1800’s. From there, it discusses Gandhi’s birth in 1869,

his childhood and adolescence in India, his college

education and life in Britain and his return to India to

advocate for the Indian people in his later adulthood.

Finally, it recounts Gandhi’s assassination in 1948 and

impact his work had on people throughout the world.

Amy Pastan wrote Gandhi to inform the reader about

Gandhi’s life. Her message is that… “Although many

thought that violence was the only way to fight this

injustice (British rule in India), Gandhi successfully

used his teaching of nonviolence and civil

disobedience to win his country’s freedom- and to

create a philosophy of peace and equality that endures

to this day.”

1869 Gandhi born in Porbandar, India

1883 Gandhi marries Kasturba

1888 Gandhi sails to England to study and practice law

1893 Gandhi serves as a legal consultant in South Africa where he experiences racial

discrimination firsthand

1906 Gandhi begins his nonviolent campaign for Indian rights

1907-1917 Gandhi organizes protests and demonstrations against unjust laws and practices in

India

1919 Amritsar Massacre occurs

1922 Gandhi is arrested and sentences to six years in prison

1924 Gandhi urges the Muslims and Hindus to work together

1930 Gandhi leads the Salt March to protest salt laws

1931 Gandhi attends the Second Round Table to discuss Dominion status for India

1932 Gandhi fasts to oppose separate elections for Untouchables

1942 Gandhi organizes the “Quit India” campaign for independence

1944 Gandhi’s wife Kasturba dies in prison

1946 Gandhi opposes the partition of India

1947 India celebrates independence from Britain

1948 Gandhi is assassinated in India

The author of Gandhi tells the story as if Gandhi was a

personal acquaintance. She relates Gandhi’s thoughts and

feelings throughout his story so that the reader can

understand why Gandhi made the choices he did. She is

also able to give enough background of the time Gandhi

lived so that the reader can follow the story of India’s

struggle to become free of British rule. She used a lot of

photographs to illustrate the story and make it easier to

follow. Amy Pastan wraps up her book with these words:

“Gandhi sacrificed himself as an individual to the greater

causes of freedom and human rights. He gave up his

possessions, time with his family, and ultimately, his life.

In death, he became a symbol of the principles he had lived

for: truth and nonviolence.” (p. 120)

People who are able to make a difference in the world are

ordinary people with extraordinary character. They are

people who stand up for right, take risks, sacrifice for

others, and refuse to give up when hardship comes.

Gandhi was just such a person. He believed that the people

of India deserved the right to be treated as equals and to

govern themselves, and he used his influence to lead the

people in nonviolent protests against unjust British laws.

He gave up his own personal wealth, often representing

people in court cases for free. He suffered in prison and

during voluntary prayer fasts to create sympathy for the

people’s plight. His life made a difference in India, in

South Africa, and even in America when Martin Luther

King, Jr. used the teachings of Gandhi to help ensure the

passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Gandhi is a book worth reading again. It contains a lot of factual

information about Gandhi’s life and accomplishments. Any

unusual terms are defined and explained so the book is fairly

easy to read. The information contained in the book is

consistent with information found in other books and websites,

but it is written so that younger or less sophisticated readers can

comprehend it. Some surprising facts found in the book Gandhi

include: Gandhi’s family was wealthy, Gandhi studied law in

England, and over one million people attended Gandhi’s funeral

in 1948. Other topics related to this book are Hinduism, Islam,

the history of India, apartheid in South Africa, the

Untouchables, and Civil Rights activism. As Gandhi was a

Hindu, a study of his religion would help the reader understand

his motivations and actions even more.

In India, the term "Untouchable" is now regarded as insulting or politically incorrect (like Eta in

Japan for the traditional tanners and pariahs). Gandhi's Harijans ("children of God") or Dalits,

("downtrodden"), are prefered, though to Americans "Untouchables" would sound more like the

gangster-busting federal agent Elliot Ness from the 1920's. Why there are so many Untouchables is

unclear, although caste Hindus can be ejected from their jâtis and become outcastes and various

tribal or formerly tribal people in India may never have been properly integrated into the social

system. When Mahâtmâ Gandhi's subcaste refused him permission to go to England, as noted above,

he went anyway and was ejected from the caste. After he returned, his family got him back in, but

while in England he was technically an outcaste. Existing tribal people as well as Untouchables are

also called the "scheduled castes" or "scheduled tribes," since the British drew up a "schedule" listing

the castes that they regarded as backwards, underprivileged, or oppressed.

The Untouchables, nevertheless, have their own traditional professions and their own subcastes.

Those professions (unless they can be evaded in the greater social mobility of modern, urban,

anonymous life) involve too much pollution to be performed by caste Hindus: (1) dealing with the

bodies of dead animals (like the sacred cattle that wander Indian villages) or unclaimed dead

humans, (2) tanning leather, from such dead animals, and manufacturing leather goods, and (3)

cleaning up the human and animal waste for which in traditional villages there is no sewer system.

Mahâtmâ Gandhi referred to the latter euphemistically as "scavenging" but saw in it the most horrible

thing imposed on the Untouchables by the caste system. His requirement on his farms in South

Africa that everyone share in such tasks comes up in an early scene in the movie Gandhi. Since Gandhi

equated suffering with holiness, he saw the Untouchables as hallowed by their miserable treatment

and so called them "Harijans" (Hari=Vis.n.u). Later Gandhi went on fasts in the hope of improving

the condition of the Untouchables, or at least to avoid their being politically classified as non-Hindus.

Ross, Kelly. From “The Caste System in India.” Retrieved at http://www.friesian.com/caste.htm on

March2, 2011.

Copyright (c) 1996, 1998, 2001, 2004, 2005, 2010 Kelley L. Ross, Ph.D. All Rights Reserved