Dr. Qaiser Fahim - Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in

advertisement

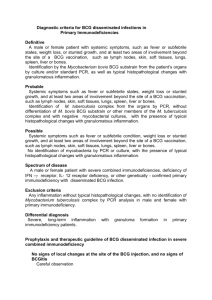

Managing a Critical Drug Shortage Utilizing an Ethical Framework 14 April 2015 1 Overview of Presentation • Context of Cancer Care in Saskatchewan • Discuss the BCG Drug Shortage and its implications • Discuss actions taken • Ethical Principles and framework utilized • Lessons learned 2 Saskatchewan Cancer Agency (SCA) • Responsible for providing leadership in cancer control through prevention, early detection, treatment, and research. • 2 Comprehensive Cancer Centres – Saskatoon Cancer Centre & Allan Blair Cancer Centre in Regina • 16 Community Oncology Centres (COPS Centres) • SCA/SHR Joint Ethics Committee 3 Media http://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitness/health/shortage-of-vital-bladder-cancer-drug-prompts-rationing/article20464929/ 4 BCG Drug Shortage BCG Live (Intravesical) OncoTICE® • FDA: “Requirements related to complying with good manufacturing practices” • Canadian Drug Shortage Database: “Manufacturing constraints in conjunction with an increased demand. Limited quantities available through allocation.” • Merck: • Informed the Sask Cancer Agency on August 20, 2014 • Reason for shortage were air quality concerns at the manufacturing plant resulting in inability to release any BCG product until cleared • Unknown how long the shortage will last – working on addressing air quality concerns and quality testing for existing BCG product “reason for the shortage is manufacturing delay.” • SCA: • Centralized purchasing, inventory management and distribution of all cancer drugs in Saskatchewan (Advantage in drug shortage situation) • Identified that a shortage BCG affects patient management – NEED A PLAN ASPH: http://www.ashp.org/menu/DrugShortages/CurrentShortages/Bulletin.aspx?id=915 Canadian Drug Shortage Database: http://www.drugshortages.ca/drugshortages.asp?x= FDA: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/SafetyAvailability/Shortages/ucm351921.htm 5 Implications of BCG Shortage • BCG (live attenuated Mycobacterium) is the standard of care for the treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancers • BCG is considered the most efficacious agent to delay tumor progression, decrease the need for surgical removal of the bladder and improve overall survival • Administered directly into the bladder • Induction treatment is weekly for 6 treatments, and depending on response, given as maintenance therapy weekly for 3 treatments for up to 3 years (generally at months 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36) Lack of access to BCG therapy: • Use of other alternatives – e.g. bladder instillation with Mitomycin and Gemcitabine – have not routinely used and have not shown to be more efficacious than BCG 6 SCA Actions • Establish exact count of BCG stock levels (locations in Regina and Saskatoon, and rural outreach centres) • Identify all patients in the province currently receiving BCG bladder instillations (centralized pharmacy computerized dispensing system). • Decision not to interrupt BCG therapy for patients currently in the middle of a weekly treatment protocol – remove the # of vials required from stock to complete each patient’s therapy and label per patient (dedicated stock) • Sequester drug centrally. All sites return remaining (undedicated) stock to the central Cancer Centre locations of Regina and Saskatoon. • Inform prescribers and treatment centres that we would develop a strategy for BCG patient allocation, and would be communicating this as soon as available. • Communication of strategy communicated to stakeholders : August 28th • Clinical triage process put in place immediately • Allocation and management of the drug shortage through the Cancer Agency pharmacy program and BCG dispensed only on an individual patient-labelled basis. • Close collaboration with supplier (Merck) regarding ongoing drug availability 7 Ethics Framework Development (9 days) Timeline 8/20/2014 - 8/28/2014 8/28/2014 10/18/2014 Ethics Framework Revised (52 Days) Day 1 6 11 16 21 26 31 36 41 46 51 56 2014 9/9/2014 SHR/SCA Ethics Committee Review of Framework 9/8/2014 8/28/2014 Media: The Globe and Mail Article SCA memo outlining BCG Drug Shortage Framework 8/27/2014 Development of Ethics Framework with Urology Physicians 8/26/2014 Stakeholder identification & SHR Pharmacy media release 10/18/2014 Ethics Framework revised due to increased drug availability. Appeals committee & process completed 8/25/2014 Temporary prioritization initiated: First Come First Serve basis 8/24/2014 Ethics Meeting with Urology Dept Head & Staff 8/22/2014 Ethics Meeting with SCA Pharmacy Dept Head 8/21/2014 Ethics Services Informed 8/20/2014 SCA Pharmacy notified of BCG Drug shortage by Merck All BCG drugs sequestered. 8 Overarching Ethical Principles Utility: (Utilitarian Approach) • Maximize the greatest possible good for the greatest possible number of individuals. Beneficence: • Maintain highest quality of safe and effective care within resource constraints. Solidarity: • Build, preserve and strengthen inter-professional, inter-institutional, inter-sectorial, and where appropriate, inter-provincial/territorial collaborations and partnerships. Equity: (Justice) • Promote just/fair access to resources. Stewardship: • Use available resources carefully and responsibly. Trust: • Foster and maintain public, patient, and health care provider confidence in the health system. 9 Accommodation for Reasonableness 1. Empowerment: There should be efforts to minimize power differences in the decision-making context and to optimize effective opportunities for participation (Gibson et al., 2005). 2. Publicity: The framework (process), decisions and their rationales should be transparent and accessible to the relevant public/stakeholders (Daniels & Sabin, 2002). 3. Relevance: Decisions should be made on the basis of reasons (i.e., evidence, principles, arguments) that “fair-minded” people can agree are relevant under the circumstances (Daniels & Sabin, 2002). 4. Revisions and Appeals: There should be opportunities to revisit and revise decisions in light of further evidence or arguments. There should be a mechanism for challenge and dispute resolution (Daniels & Sabin, 2002). 5. Compliance (Enforcement): There should be either voluntary or public regulation of the process to ensure that the other four conditions are met (Daniels & Sabin, 2002). 10 Allocation Principles 1. Justice : Continue treatment of patients currently on tx. • All patients currently on treatment are prioritized to enable them to complete their current treatment cycle (induction or maintenance) regardless of risk. • After completion of their current treatment cycle they will receive treatment according to this framework. 11 Allocation Principles 2. Maximizing Therapeutic Benefit: Initiate treatment of newly diagnosed high risk pts. a) New Patients: Patients who are newly diagnosed with high risk disease (T1 high grade, Ta high grade, or CIS) or recurrent and require BCG induction therapy of weekly x 6 treatments. b) Maintenance Therapy Patients: Those who have high risk disease (T1 high grade, Ta high grade, or CIS) who are in remission and who will begin a maintenance course of weekly x 3 treatments at 3 months or 6 months post‐induction. 12 Allocation Principles 3. Maximizing Utility: Delay in treatment/ tx. on hold: a) Delay in Maintenance Treatment: • Those who have high risk disease (T1 high grade, Ta high grade, or CIS) who are in remission and are to begin a maintenance course of weekly x 3 treatments at 12 months, 18 months, or 24 months post-induction. • These patients will be re‐evaluated after 1 month. b) Maintenance Treatment on Hold: • Those who are in remission and are to begin a maintenance course of weekly x 3 treatment >24 months post‐induction, usually at 30 months or 36 months. • Those who are to begin BCG therapy for any low grade disease, including those with multiple recurrences. 13 Allocation Principles 4. Reprioritization when resources increase: a). Maximize benefit to patients in category 3a first. b). Maximize benefit to patients in category 3b second. 14 Strategies Implement strategies to preserve standard of care and best practices to the greatest extent possible within available drug supply. Conserve existing supply of drugs. • • • • • • • • • • Consolidate all available BCG drug at the Saskatchewan Cancer Agency and distribute provincially according to this framework. Standardize treatment practices across the province. Develop an inventory of available drugs across care settings based on available supply and criticality of need and/or demand Review current drug prescribing practices based on available evidence of clinical efficacy Reduce wastage of drugs Ensure adherence to standard of practice that is evidence based. Use alternative drugs or treatments where evidence suggests similar clinical efficacy to the drug in short supply Delay enrolment in research studies using drugs in short supply and all elective use of the drug as well as off label use. Reassess patients' medical needs on an ongoing basis to identify any changes in level of priority, and Maintain therapeutic relationship with patients and provide ongoing support. 15 Strategies Access new supply of drugs by: • Collaborating with other provinces and Health Canada to identify and procure alternative sources. • Redistributing drugs between care settings in coordination with key stakeholders in accordance with the ethical framework. 16 Lesson’s Learned • Benefit of having one organization in control of the drug • Importance of managing the shortage quickly • Importance of a Communication strategy • Don’t assume that Standard of Care is followed by all • Patient involvement early on 17 References • Based on the Ontario Ethical Framework for Resource Allocation During the Drug Supply Shortage. • Modified and used with permission from Jennifer Gibson, Ph.D., Director of Partnerships & Strategy at the Joint Centre for Bioethics at the University of Toronto, 30 March 2012. • The IDEA: Ethical Decision-Making Framework builds upon the Toronto Central Community Care Access Centre Community Ethics Toolkit (2008), which was based on the work of Jonsen, Seigler, & Winslade (2002); the work of the Core Curriculum Working Group at the University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics; and incorporates aspects of the accountability for reasonableness framework developed by Daniels and Sabin (2002) and adapted by Gibson, Martin, & Singer (2005). 18 Questions 19