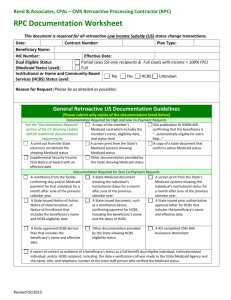

HCBS Program Evaluation Review

advertisement