presentation ( format)

advertisement

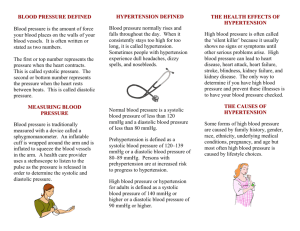

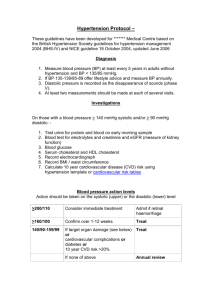

The Changing Paradigm of Hypertension: Victoria E. Judd M. D. Objectives • Define hypertension • Discuss the diagnosis and evaluation of hypertension • List the management of hypertension • List the complications of hypertension Hypertension • Most common disease of industrialized world (>20% of adult population) • Major risk factor for death from heart attack, stroke, congestive heart failure,kidney disease, retinopathy, peripheral vascular disease • Pathogenesis unknown • Treatment inadequate What is Hypertension? • The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) Definition of Hypertension These definitions apply to: • Adults • On no antihypertensive medications • Who are not acutely ill Definition of Hypertension • If there is a disparity in category between the systolic and diastolic pressures, the higher value determines the severity of the hypertension. Definition of Hypertension • The systolic pressure is the greater predictor of risk in patients over the age of 50 to 60. Definition of Hypertension • Somewhat different definitions were suggested by the European Societies of Hypertension and Cardiology, which published 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Definition of Hypertension • Optimal blood pressure: systolic <120 mmHg and diastolic <80 mmHg • Normal: systolic 120-129 mmHg and/or diastolic 80-84 mmHg • High normal: systolic 130-139 mmHg and/or diastolic 85-89 mmHg Definition of Hypertension • • • • Hypertension: Grade 1: systolic 140-159 mmHg and/or diastolic 90-99 mmHg Grade 2: systolic 160-179 mmHg and/or diastolic 100-109 mmHg Grade 3: systolic ≥180 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥110 mmHg Isolated systolic hypertension: systolic ≥140 mmHg and diastolic <90 mmHg Resistant Hypertension • Blood pressure that remains above goal despite the concurrent use of 3 antihypertensive agents of 3 different classes. Definition of Malignant Hypertension • Malignant hypertension is marked hypertension with retinal hemorrhages, exudates, or papilledema. • Malignant hypertension is usually associated with a diastolic pressure above 120 mmHg. Definitions • Hypertensive encephalopathy can be seen at diastolic pressures as low as 100 mmHg in previously normotensive patients with acute hypertension due to preeclampsia or acute glomerulonephritis. • In patients in whom autoregulation is impaired may also develop hypertensive injury at relatively mild degrees of hypertension. Diagnosis of Hypertension • The optimal interval for screening for hypertension is not known. The 2007 United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines on screening for high blood pressure recommend screening every two years for persons with systolic and diastolic pressures below 120 mmHg and 80 mmHg, respectively (normal BP in JNC 7), and yearly for persons with a systolic pressure of 120 to 139 mmHg or a diastolic pressure of 80 to 89 mmHg. Diagnosis of Hypertension • Proper measurement and interpretation of the blood pressure is essential in the diagnosis and management of hypertension. Diagnosis of Hypertension • A recent study found no clinical difference in blood pressure readings from a bare arm compared to those measured over a sleeved arm. • A comparison of blood pressure measurement over a sleeved arm versus a bare arm. Ma G; Sabin N; Dawes M; CMAJ. 2008 Feb 26;178(5):585-9. Diagnosis of Hypertension • In the absence of end-organ damage, the diagnosis of mild hypertension should not be made until the blood pressure has been measured on at least three to six visits, spaced over a period of weeks to months. Diagnosis of Hypertension • Sequential studies have shown that the blood pressure drops by an average of 10 to 15 mmHg between visits one and three in patients who appear to have mild hypertension on a first visit to a new provider, with a stable value not being achieved until more than six visits in some cases. Diagnosis of Hypertension • Thus, many patients considered to be hypertensive at the initial visit are in fact normotensive. • Confirming the diagnosis of mild hypertension. Hartley RM; Velez R; Morris RW; D'Souza MF; Heller RF; Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983 Jan 22;286(6361):287-9. Diagnosis of Hypertension • Variation in cuff blood pressure in untreated outpatients with mild hypertension-implications for initiating antihypertensive treatment. Watson RD; Lumb R; Young MA; Stallard TJ; Davies P; Littler WA; J Hypertens 1987 Apr;5(2):207-11. Circumstances of BP Measurements • No caffeine during the hour preceding the measurement and no smoking during the preceding 30 minutes • No exogenous adrenergic stimulants, such as phenylephrine in decongestants or eye drops for pupillary dilatation • A quiet, warm setting • Home readings should be taken upon varying circumstances Equipment for BP Measurement Cuff size • The length of the bladder should be 80 percent and the width of the bladder should be at least 40 percent of the circumference of the upper arm. BP Measurement • Take at least two measurements on each visit, separated by as much time as possible; if measurements vary by more than 5 mmHg, take additional measurements until two consecutive measurements are close. BP Measurement • For the diagnosis of hypertension, take three measurements at least one week apart. • Initially, take blood pressure in both arms; if pressures differ, use the higher arm. • If the arm pressure is elevated, take the pressure in one leg, particularly in patients under age 30. BP Measurement • Inflate the bladder quickly to 20 mmHg above the systolic pressure as estimated from loss of radial pulse • Deflate the bladder 3 mmHg per second BP Measurement • Record the Korotkoff phase V (disappearance) as the diastolic pressure. • If the Korotkoff sounds are weak, have the patient raise the arm, open and close the hand five to ten times, and then inflate the bladder quickly. Hypertensive Response to Visit • Increase in systolic pressure, determined by continuous intraarterial monitoring, in 30 hypertensive patients as the blood pressure is taken with a sphygmomanometer by an unfamiliar doctor or nurse. A new doctor's visit raised the systolic pressure by a mean of 22 mmHg within the first few minutes, an effect that attenuated within five to 10 minutes and that was less pronounced with a nurse's visit. The alerting effect of the new physician's visit persisted for four daily visits in this study, but typically diminished with increasing familiarity. A similar pattern was seen with the diastolic pressure, with the peak increase being 13 mmHg during a physician's visit. Data from Mancia, G, Parati, G, Pomidossi, G, et al, Hypertension 1987; 9:209. BP Measurement Recordings • Note the pressure, patient position, arm, and cuff size: e.g., 140/90, seated, right arm, large adult cuff BP Overestimated • • • • • • Arm below heart Small cuff Talking Cold temperature Alcohol Tobacco BP Underestimated • • • • Arm above heart Cuff too large Supine Provider bias ABPM • ABPM is determined using a device worn by the patient that takes blood pressure measurements over a 24 to 48 hour period, usually every 15 to 20 minutes during the daytime and every 30 to 60 minutes during sleep. ABPM • These blood pressures are recorded on the device, and the average day (diurnal) or night (nocturnal) blood pressures are determined from the data by a computer. ABPM • The percentage of blood pressure readings exceeding the upper limit of normal can also be calculated. • This is considered to provide a better measure of systolic and diastolic blood pressure load than an individual blood pressure measurement. ABPM • However, ABPM is not available in many clinicians' offices. This is probably due to a combination of factors, including lack of knowledge regarding its utility, its expense, and minimal reimbursement by third-party payers. • In addition, ABPM is still only a onetime measure of a variable factor that must be followed over time. Definition of Hypertension by ABPM • A 24-hour average above 135/85 mmHg • Daytime (awake) average above 140/90 mmHg • Nighttime (asleep) average above 125/75 mmHg ABPM • In two separate community based studies, with 1700 and 5292 participants, multivariate analysis demonstrated that only ambulatory blood pressures (and not office blood pressures) were significant predictors of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality after a mean follow-up of over eight years. ABPM • Ambulatory blood pressure and mortality: a populationbased study. Hansen TW; Jeppesen J; Rasmussen S; Ibsen H; Torp-Pedersen C; Hypertension 2005 Apr;45(4):499504. Epub 2005 Mar 7. • Superiority of ambulatory over clinic blood pressure measurement in predicting mortality: the Dublin outcome study. Dolan E; Stanton A; Thijs L; Hinedi K; Atkins N; McClory S; Den Hond E; McCormack P; Staessen JA; O'Brien E. Hypertension 2005 Jul;46(1):156-61. Epub 2005 Jun 6. ABPM • Some, but not all, data suggest that measurement of nighttime blood pressure may yield additional prognostic data in terms of all cause mortality and cardiovascular events. ABPM • A cohort study of 7458 patients in six countries from Europe, Asia, and South America found that both daytime and nighttime blood pressure predicted all cardiovascular events. • Nighttime blood pressure, adjusted for day time blood pressure, predicted total, cardiovascular, and noncardiovascular mortality. • In contrast, daytime blood pressure, adjusted for blood pressure measured during sleep, only predicted noncardiovascular mortality. ABPM • Similar findings were noted in a second cohort of 3957 patients who underwent ambulatory monitoring. • Blood pressures obtained during sleep were more predictive of allcause mortality than those obtained during waking hours. When to Get ABPM • Suspected white coat hypertension • Suspected episodic hypertension (e.g., pheochromocytoma) • Hypertension resistant to increasing medication • Hypotensive symptoms while taking antihypertensive medications • Autonomic dysfunction Home BPM • In view of the cost and limited availability of ambulatory monitoring, increasing attention is being given to home monitoring with inexpensive semi-automatic devices. Home BPM • Such self-recorded casual blood pressure measurements taken at home or work correlate more closely with the results of 24-hour or daytime ambulatory monitoring than with blood pressure taken in the physician's office. Home BPM • Home blood pressure measurements may be more predictive of adverse outcomes (e.g., stroke, ESRD) than clinic blood pressures. Home BPM • Patient self-monitoring of blood pressure may improve blood pressure control. • A systematic review found a 4 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure among patients instructed to measure blood pressure themselves. Home BPM • The potential problems with outpatient BP measurements can be minimized by providing adequate training, and periodically checking the machine for accuracy. • These can be tested by having the patient or their partner take the BP in the office with their home monitor at the same time that a medical person measures the BP in the other arm. Home BPM • As with ambulatory monitoring, the BP taken by the patient varies widely during the day, being influenced by factors such as stress (particularly at school, work), smoking, caffeine intake, natural circadian variation, and exercise. • Thus, multiple readings should be taken to determine the average level. Home BPM • The timing of antihypertensive medication must also be considered. With short-acting drugs, the BP may fall to normal or even below normal one to two hours after therapy and then gradually increase to elevated levels until the next dose is taken. • This problem can be minimized by having the outpatient BP measured 30 to 60 minutes before taking medications, preferably in the early morning to assess for possible inadequate overnight BP control. Evaluation of Hypertension • To rule out identifiable and often curable causes of hypertension. • To determine the extent of target organ damage. • To assess the patient's overall cardiovascular risk status. History Duration of hypertension • Last known normal blood pressure • Course of the blood pressureincreasing, decreasing, stable History Prior treatment of hypertension • Drugs: types, doses, side effects History Intake of agents that may cause hypertension • Estrogens • Adrenal steroids • Cocaine • Sympathomimetics; i.e. amphetamines • Excessive sodium History Family history • Hypertension • Premature cardiovascular disease or death • Familial diseases: pheochromocytoma, renal disease, diabetes History Symptoms of secondary causes • Muscle weakness • Spells of tachycardia, sweating, tremor • Thinning of the skin • Flank pain History Symptoms of target organ damage • Headaches • Transient weakness or blindness • Loss of visual acuity • Chest pain • Dyspnea • Claudication History Presence of other risk factors • Smoking • Diabetes • Dyslipidemia • Physical inactivity History Dietary history • Sodium • Alcohol • Saturated fats History Psychosocial factors • Support structure • Work status • Educational stressors History Features of sleep apnea • Early morning headaches • Daytime somnolence • Loud snoring • Erratic sleep Physical Exam • Accurate measurement of blood pressure Physical Exam General appearance • Distribution of body fat • Skin lesions • Muscle strength • Alertness Physical Exam Fundoscopy • Hemorrhage • Papilledema • Cotton-wool spots Physical Exam Neck • Palpation and auscultation of carotids • Thyroid • Neck circumference in inches Physical Exam Heart • Size • Rhythm • Sounds Physical Exam Lungs • Rhonchi • Rales Physical Exam Abdomen • Renal masses • Bruits over aorta or renal arteries • Femoral pulses Physical Exam Extremities • Peripheral pulses • Edema Physical Exam Neurologic assessment • Visual disturbance • Focal weakness • Confusion Laboratory • Complete blood count, routine blood chemistries (hemolysis, thrombocytopenia, acute renal failure) • Lipid profile (Should be done fasting) • Urinalysis (proteinuria, hematuria) • Electrocardiogram (myocardial ischemia, hypertrophy) Laboratory • Additional tests may be indicated in certain settings. Hypertension • Primary (essential) 95% • Secondary 5% (has a demonstrable cause) Secondary Hypertension is Suggested By • Severe or refractory hypertension. • An acute rise in blood pressure over a previously stable value. • Proven age of onset before puberty. • Age less than 30 years in non-obese, non-black patients with a confirmed negative family history of hypertension. Renovascular Hypertension • Renovascular hypertension is the most common correctable cause of secondary hypertension. Renovascular Hypertension • The following are settings in which renovascular hypertension or another cause of secondary hypertension should be suspected: Renovascular Hypertension • Proven age of onset before puberty or above age 50. • Negative family history for hypertension. Renovascular Hypertension • A systolic-diastolic abdominal bruit that lateralizes to one side. This finding has a sensitivity of approximately 40 percent (and is therefore absent in many patients) but has a specificity as high as 99 percent. • Systolic bruits alone are more sensitive but less specific. • The patient should be supine, moderate pressure should be placed on the diaphragm of the stethoscope, and auscultation should be performed in the epigastrium and all four abdominal quadrants. Other Causes of Identifiable Hypertension • Pheochromocytoma should be suspected if there are paroxysmal elevations in blood pressure (which may be superimposed upon stable chronic hypertension), particularly if associated with the triad of headache (usually pounding), palpitations, and sweating. Other Causes of Identifiable Hypertension • Cushing's syndrome (including that due to corticosteroid administration) is usually suggested by the classic physical findings of cushingoid facies, central obesity, ecchymoses, and muscle weakness. Other Causes of Identifiable Hypertension • Coarctation of the aorta is characterized by decreased or lagging peripheral pulses and a vascular bruit over the back. Components of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with hypertension Major risk factors • • • • • Cigarette smoking Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) Physical inactivity Dyslipidemia Diabetes mellitus Components of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with hypertension • Microalbuminuria or estimated GFR <60 mL/min • Age >55 years for men, >65 years in women • Family history of premature coronary disease; Men - <55 years,Women - <65 years Target Organ Damage • • • • Heart disease Left ventricular hypertrophy Angina or prior myocardial infarction Prior coronary revascularization Heart failure Stroke or transient ischemic attack Chronic kidney disease Peripheral arterial disease Retinopathy Why Treat • In clinical trials, antihypertensive therapy compared to placebo has been associated with significant 20 to 25 percent reduction in the incidence of major cardiovascular events (e.g., stroke, heart failure, and myocardial infarction). Why Treat • The cardiovascular benefit may be even greater with optimal control to below 130/80 mmHg, which is currently recommended in patients with diabetes, coronary disease, or a coronary equivalent. Why Treat • Preventing heart disease by controlling hypertension: impact of hypertensive subtype, stage, age, and sex. Wong ND; Thakral G; Franklin SS; L'Italien GJ; Jacobs MJ; Whyte JL; Lapuerta P. Am Heart J 2003 May;145(5):888-95. Recommendation Maintain normal body weight (BMI, 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2) Consume a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products with a reduced content of saturated and total fat Reduce dietary sodium intake to no more than 100 meq/day (2.4 g sodium or 6 g sodium chloride) Engage in regular aerobic physical activity such as brisk walking (at least 30 minutes per day, most days of the week) Limit consumption to no more than 2 drinks per day in most men and no more than 1 drink per day in women and lighter-weight persons Approximate systolic BP reduction, range* 5-20 mmHg per 10kg weight loss 8 to 14 mmHg 2 to 8 mmHg 4 to 9 mmHg 2 to 4 mmHg Who Should be Treated? • There should be clear evidence of likely benefit before antihypertensive drugs are begun. • Such evidence is now available for most degrees of hypertension (diastolic pressure persistently ≥90 mmHg and systolic pressure ≥140 mmHg). Cardiovascular Benefit of Treating Mild Hypertension Cardiovascular Benefit of Treating Mild Hypertension • Reduced incidence of fatal and total coronary heart disease (CHD) events and strokes following antihypertensive therapy in 17 controlled studies involving almost 48,000 patients with mild to moderate hypertension. The number of patients having each of these events is depicted, with active treatment lowering the incidence of coronary events by 16 percent and stroke by 40 percent. However, the absolute benefit - as shown, in percent, by the numbers at the top of the graph was much less. Treatment for approximately 4 to 5 years prevented a coronary event or a stroke in two percent of patients (0.7 + 1.3), including prevention of death in 0.8 percent. • Data from Hebert, PR, Moser, M, Mayer, J, et al, Arch Intern Med 1993; 153:578. Who Should be Treated? • There are controversial data suggesting that treatment of prehypertension may lower the risk of developing sustained hypertension. (TROPHY trial). Who Should be Treated? • In general, epidemiologic studies of treated and untreated patients reveal that there is a gradually increasing incidence of coronary disease and stroke and cardiovascular mortality as the blood pressure rises above 110/75 mmHg, with some notable differences in risk based upon age and underlying comorbid conditions. Who Should be Treated? • The Framingham Heart Study also reported an increased incidence of poor outcomes as the blood pressure rises, even with values within the "normal" range. • This study examined the risk of cardiovascular disease at 10 year follow-up among subjects with "high-normal" blood pressure at baseline examination, which was defined as a systolic blood pressure of 130 to 139 mmHg, a diastolic pressure of 85 to 89 mmHg, or both, and with "normal" blood pressure, which was defined as a systolic blood pressure of 120 to 129 mmHg, a diastolic pressure of 80 to 84 mmHg, or both. Who Should be Treated? • Cumulative incidence of cardiovascular events over time in 6859 men and women in the Framingham Heart Study who were initially free of hypertension or cardiovascular disease. The patients were put into one of three BP categories: optimal blood pressure (BP 120/ 80), normal BP (120 to 129/80-84), and high-normal BP (130-139/8589 mmHg). If the systolic and diastolic pressures were discordant, the higher of the two categories was used. High-normal BP, compared to optimal BP, was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio for cardiovascular disease of 1.6 in men and 2.5 in women. Data from Vasan, RS, Larson, MG, Leip, EP, et al, N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1291. Treatment • In the Women's Health Initiative study involving over 60,785 postmenopausal women who were followed for 7.7 years, women with prehypertension, compared to normotensive individuals, had an increased risk of cardiovascular death (HR 1.76, 95% CI 1.40 to 2.2), myocardial infarction (1.93, 95% CI 1.49 to 2.50) and stroke (1.36, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.77). Treatment • Prehypertension and cardiovascular disease risk in the Women's Health Initiative. Hsia J; Margolis KL; Eaton CB; Wenger NK; Allison M; Wu L; LaCroix AZ; Black HR. Circulation. 2007 Feb 20;115(7):855-60. Who Should be Treated? • The Medical Research Council Mild Hypertension Trial found a close correlation between cardiovascular risk and the systolic pressure measured three months after entry into the trial. In contrast, a transient increase in systolic pressure at entry due to a white coat response was not associated with increased risk. Who Should be Treated? • Antihypertensive medications should generally be begun if the systolic pressure is persistently ≥140 mmHg and/or the diastolic pressure is persistently ≥90 mmHg in the office and at home despite attempted nonpharmacologic therapy. Who Should be Treated? • In patients with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or known cardiovascular disease, antihypertensive therapy is indicated when the systolic pressure is persistently above 130 mmHg and/or the diastolic pressure is above 80 mmHg. Who Should be Treated? • 5 to 20 percent of patients with normal office readings have been found to have elevated out-of-the office readings by 24 hour automatic ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. • These patients with "masked" hypertension appear to have an increased cardiovascular risk similar to those with elevated office and ambulatory readings. Treatment • Although recommendations for initiating medical therapy in essential hypertension have been proposed, there is no uniform agreement on which antihypertensive agent should be given for initial therapy. Treatment • A variety of different classes of drugs can be used in this setting. These include the thiazide diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB’s), calcium channel blockers, and beta blockers. Treatment • The choice among the different antihypertensive drugs has not generally been made on the basis of efficacy, since each of these agents is roughly equally effective, producing a good antihypertensive response in 30 to 50 percent of cases. Treatment • An increasing number of trials have provided evidence that, at the same level of blood pressure control, most antihypertensive drugs provide the same degree of cardiovascular protection, particularly cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Treatment • The 2007 American Heart Association statement on the treatment of blood pressure in ischemic heart disease, the 2007 European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology guidelines on the management of hypertension, and a 2008 meta-analysis concluded that the amount of blood pressure reduction is the major determinant of reduction in cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertension, not the choice of antihypertensive drug. Treatment • • Effects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta-analysis of randomised trials. Turnbull F; Neal B; Ninomiya T; Algert C; Arima H; Barzi F; Bulpitt C; Chalmers J; Fagard R; Gleason A; Heritier S; Li N; Perkovic V; Woodward M; MacMahon S. BMJ. 2008 May 17;336(7653):1121-3. Epub 2008 May 14. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Rosendorff C; Black HR; Cannon CP; Gersh BJ; Gore J; Izzo JL Jr; Kaplan NM; O'Connor CM; O'Gara PT; Oparil S. Circulation. 2007 May 29;115(21):2761-88. Epub 2007 May 14. Treatment • • 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Mancia G; De Backer G; Dominiczak A; Cifkova R; Fagard R; Germano G; Grassi G; Heagerty AM; Kjeldsen SE; Laurent S; Narkiewicz K; Ruilope L; Rynkiewicz A; Schmieder RE; Struijker Boudier HA; Zanchetti A; Vahanian A; Camm J; De Caterina R; Dean V; Dickstein K; Filippatos G; Funck-Brentano C; Hellemans I; Kristensen SD; McGregor K; Sechtem U; Silber S; Tendera M; Widimsky P; Zamorano JL; Kjeldsen SE; Erdine S; Narkiewicz K; Kiowski W; Agabiti-Rosei E; Ambrosioni E; Cifkova R; Dominiczak A; Fagard R; Heagerty AM; Laurent S; Lindholm LH; Mancia G; Manolis A; Nilsson PM; Redon J; Schmieder RE; Struijker-Boudier HA; Viigimaa M; Filippatos G; Adamopoulos S; Agabiti-Rosei E; Ambrosioni E; Bertomeu V; Clement D; Erdine S; Farsang C; Gaita D; Kiowski W; Lip G; Mallion JM; Manolis AJ; Nilsson PM; O'brien E; Ponikowski P; Redon J; Ruschitzka F; Tamargo J; van Zwieten P; Viigimaa M; Waeber B; Williams B; Zamorano JL . Eur Heart J. 2007 Jun;28(12):1462-536. Epub 2007 Jun 11. Treatment • In the absence of a specific indication, there are three main classes of drugs that are used for initial monotherapy: thiazide diuretics, long-acting calcium channel blockers (most often a dihydropyridine), and ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers. Treatment • It is the attained blood pressure, not the specific drug(s) used, that is the primary determinant of outcome. • Beta blockers are not commonly used for initial monotherapy in the absence of a specific indication, since they may have an adverse effect on some cardiovascular outcomes, particularly in older patients. Treatment • Beta blockers as initial therapy? — It is unclear whether beta blockers offer the same degree of cardiovascular protection as other antihypertensive drugs in patients with essential hypertension who have no specific indications for their use (e.g., resting tachycardia, angina pectoris, or a recent myocardial infarction). Treatment • There may be some differences in selected outcomes, such as stroke, or in noncardiovascular outcomes such as the development of diabetes, and differences based on patient characteristics, such as presence of diabetes and race. Treatment • These observations led to a general consensus, including 2007 guidelines from the American Heart Association and European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology, that the amount of BP reduction is the major determinant of reduction in cardiovascular risk, not the choice of antihypertensive drug. Treatment • However, based upon the results of the ACCOMPLISH trial, this conclusion about equivalent efficacy of the different drugs may not apply to combination therapy. Treatment • ACCOMPOLISH: Avoiding Cardiovascular Events in Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension Treatment ALLHAT: The Antihypertensive and LipidLowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial ALLHAT • ALLHAT was designed to evaluate whether the incidence of adverse cardiovascular outcomes differed among those randomly assigned to chlorthalidone (12.5 to a maximum of 25 mg/day, the equivalent dose of of hydrochlorothiazide is 1.5 to 2.0 times higher) compared to one of three other antihypertensive drugs: amlodipine (a calcium channel blocker), lisinopril (an ACE inhibitor), or doxazosin (an alphaadrenergic blocker). ALLHAT • The doxazosin arm was terminated prematurely because of a significantly increased risk of heart failure compared to chlorthalidone (relative risk 2.0 after adjusting for a 3 mmHg higher in-trial systolic pressure with doxazosin) noted during an interim analysis and a smaller increase in stroke and all cardiovascular events. ALLHAT • The incidence of the primary outcome (fatal coronary heart disease and nonfatal myocardial infarction), and all-cause mortality were the same for all three agents. ALLHAT • A higher rate of heart failure was observed with amlodipine compared with chlorthalidone (10.2 versus 7.7 percent, RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.25-1.52) ALLHAT • Compared with chlorthalidone, lisinopril had higher rates of combined cardiovascular disease outcomes (33.3 versus 30.9 percent, RR 1.10), stroke (6.3 versus 5.6 percent, RR 1.15), and heart failure (8.7 versus 7.7 percent, RR 1.19). ALLHAT • The principal finding of ALLHAT is that chlorthalidone, amlodipine, and lisinopril provided similar protection from coronary heart disease death and nonfatal myocardial infarction among patients with hypertension and risk factors for cardiovascular disease, a result consistent with CAPPP, STOP Hypertension 2, and other trials. ALLHAT • Unlike the smaller trials previously reviewed, the large number of participants in ALLHAT provided the power to detect that a thiazide diuretic may actually be superior to a calcium channel blocker and an ACE inhibitor in preventing some adverse cardiovascular outcomes. ALLHAT • One possible explanation for this unexpected result is that lisinopril provided relatively less blood pressure control than chlorthalidone, as the first two years of the trial were associated with a 3 to 4 mmHg higher blood pressure with the ACE inhibitor. Chlorthalidone versus Hydrochlorothiazide • Chlorthalidone at the same dose is approximately 1.5 to 2.0 times as potent as hydrochlorothiazide. Thus, 12.5 mg/day of chlorthalidone is equivalent to 19 to 25 mg/day of hydrochlorothiazide. Chlorthalidone versus Hydrochlorothiazide • Based on the above observations, experts suggest that chlorthalidone (12.5 to 25 mg/day) is the low-dose thiazide diuretic of choice. • However, the choice may vary with the clinical setting. Chlorthalidone versus Hydrochlorothiazide • A possibly more important difference than potency is the longer duration of action of chlorthalidone (24 to 72 hours versus 6 to 12 hours with hydrochlorothiazide). Chlorthalidone versus Hydrochlorothiazide • Given the lower potency of hydrochlorothiazide at the same dose and its shorter duration of action, one cannot conclude in the absence of evidence that 12.5 mg/day of hydrochlorothiazide will produce the same benefit as 12.5 mg/day of chlorthalidone. Chlorthalidone versus Hydrochlorothiazide • Furthermore, the evidence supporting the efficacy of thiazide diuretics in the management of hypertension comes primarily from trials using chlorthalidone, such as ALLHAT. Chlorthalidone versus Hydrochlorothiazide • There is little if any evidence that hydrochlorothiazide alone in a dose of 12.5 to 25 mg/day reduces cardiovascular events and the blood pressure may not be as wellcontrolled overnight. Chlorthalidone versus Hydrochlorothiazide • In addition, in the ACCOMPLISH trial, which compared combination therapy with benazepril plus either hydrochlorothiazide (12.5 to 25 mg/day) or amlodipine, cardiovascular outcomes were worse in the benazeprilhydrochlorothiazide group. Chlorthalidone versus Hydrochlorothiazide Jamerson, K. et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2417–2428 (2008). Treatment • Single agent therapy does not control the blood pressure in some patients at diagnosis (particularly those more than 20/10 mmHg above goal) and, over time, in an increasing proportion of patients who were initially controlled with monotherapy (e.g., approximately 40 percent at five years in the ALLHAT trial compared to approximately 30 percent at one year). What to Use? • Thiazide-type diuretics • Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) • Calcium channel blockers • Beta blockers, which are now used less often for initial therapy in the absence of a specific indication for their use Antihypertensive response to different drugs in whites Antihypertensive response to different drugs in whites • Response rates to single drug therapy for hypertension in whites under the age of 60. There were no significant differences in response, except that hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) appeared to be least effective. A response was defined as a diastolic pressure below 90 mmHg at the end of the titration phase and below 95 mmHg at one year. The pattern of response was similar but the success rate for each drug was reduced by five to 15 percent if goal diastolic pressure were less than 90 mmHg at one year. There were between 30 and 39 patients in each group. Data from Materson, BJ, Reda, DJ, Cushman, WC, et al, N Engl J Med 1993; 328:914. Correction and additional data: Am J Hypertens 1995; 8:189. Antihypertensive response to different drugs in blacks Antihypertensive response to different drugs in blacks • Response rates to single drug therapy for hypertension in blacks over the age of 60 years. The highest response was seen with diltiazem and hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) and the lowest with captopril. A response was defined as a diastolic pressure below 90 mmHg at the end of the titration phase and below 95 mmHg at one year. The pattern of response was similar but the success rate for each drug was reduced by five to 15 percent if goal diastolic pressure were less than 90 mmHg at one year. There were between 42 and 53 patients in each group. Data from Materson, BJ, Reda, DJ, Cushman, WC, et al, N Engl J Med 1993; 328:914. Correction and additional data: Am J Hypertens 1995; 8:189. Choice of Thiazide Diuretics • In most patients not previously treated with a thiazide diuretic, it is suggest to use low-dose chlorthalidone, rather than hydrochlorothiazide. • However, among frail older patients who are less than 10 mmHg above goal blood pressure, some consider low-dose hydrochlorothiazide a reasonable alternative. Choice of Thiazide Diuretics • Chlorthaloidone is not available in all formularies and pharmacies. • There is no 12.5 mg tablet. Thus, 25 mg tablets of generic chlorthalidone need to be cut in half. There is a more expensive 15 mg brand name preparation (Thalitone®). • This preparation has greater bioavailability than generic chlorthalidone, and clinical studies suggest that its antihypertensive efficacy is closer to 25 mg of generic chlorthalidone. Choice of Thiazide Diuretic • Low-dose hydrochlorothiazide (12.5 to a maximum of 25 mg/day) is widely used and, after publication of the ALLHAT trial, was recommended as initial monotherapy in most patients with mild essential hypertension by JNC 7 and others. • However, hydrochlorothiazide is less effective and has a shorter duration of action than chlorthalidone, and there is little, if any, evidence that low-dose hydrochlorothiazide alone reduces cardiovascular events as opposed to the evidence with chlorthalidone. Thiazide Diuretic Risks of; • Hypokalemia • Glucose intolerance • New onset diabetes mellitus Dose-dependence of thiazide-induced side effects Dose-dependence of thiazide-induced side effects • Metabolic complications induced by bendrofluazide in relation to daily dose (multiply by 10 to get equivalent doses of hydrochlorothiazide). Increasing the dose led to progressive hypokalemia and hyperuricemia and a greater likelihood of a mild elevation in the fasting blood glucose (FBG), all without a further reduction in the systemic blood pressure. Each treatment group contained approximately 52 patients. Data from Carlsen, JE, Kober, L, Torp-Pedersen, C, Johannsen, P, BMJ 1990; 300:975. Treatment • Younger patients respond best to angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARBs). Treatment • Support for this differential antihypertensive response in younger patients is supported by a study of 56 young (22 to 51 years) white hypertensive patients who were treated in a crossover rotation with the four main classes of antihypertensive drugs: ACE inhibitor, thiazide diuretic, long-acting dihydropyridine CCB, and beta blocker. • Significantly greater responses in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels were noted with the ACE inhibitor and beta blocker than with the CCB or diuretic. Treatment • Optimisation of antihypertensive treatment by crossover rotation of four major classes. Dickerson JE; Hingorani AD; Ashby MJ; Palmer CR; Brown MJ. Lancet 1999 Jun 12;353(9169):2008-13. Treatment • Each of the recommended first-line agents will normalize the BP in 30 to 50 percent of patients with mild hypertension. • A patient who is relatively unresponsive to one drug has an almost 50 percent likelihood of becoming normotensive on a second drug. Treatment: ACE Risks Hypotension • dizziness • syncope • weakness Treatment: ACE Risks Acute Renal Failure • A decline in renal function, that is usually modest but may be severe, may be observed in some patients with bilateral renal artery stenosis, hypertensive nephrosclerosis, congestive heart failure, polycystic kidney disease, or chronic renal failure. Treatment: ACE Risks Hyperkalemia In pregnant women or women who may become pregnant, ACE inhibitors are associated with increased teratogenic risk to the fetus. Treatment: ACE Risks Cough • It usually begins within one to two weeks of instituting therapy, but can be delayed up to six months. • Women are affected more frequently than men. • Chinese, at least in Hong Kong, have a high prevalence that approaches 50 percent. Treatment: ACE Risks Cough • It typically resolves within one to four days of discontinuing therapy, but can take up to four weeks. • It generally recurs with rechallenge, either with the same or a different ACE inhibitor. • It does not occur more frequently in asthmatics than in nonasthmatics but it may be accompanied by bronchospasm. Treatment: ACE Risks • Treatment consists of lowering the dose or discontinuing the drug, which will lead to resolution of the cough. • Improvement often begins within four to seven days but may persist for three to four weeks or more in some patients. • Readministration of an ACE inhibitor is associated with a high rate of recurrent cough (67 percent in a randomized trial). Treatment:ARBs Risks Cough • The incidence of cough is lower in patients treated with ARBs. ARBs should not be given to pregnant women or those who may become pregnant. Treatment: ARBs Risks Angioedema • The risk of angioedema appears to be lower with ARBs than ACE inhibitors. Treatment:ARBs Risks Hypotension • Hypotension appears to be more common with ARBs than ACE inhibitors. Treatment Risks • Nifedipine and related drugs induce the most prominent direct vasodilation, an effect that can lead to dizziness, headache, flushing, and peripheral edema. • In comparison, decreased cardiac contractility, reduced cardiac conduction, and constipation are most likely to be seen with verapamil. • Diltiazem has an intermediate effect on these parameters and appears to be associated with the lowest incidence of adverse effects. Treatment Effects on Lipids • High doses (50 mg/day or more) of thiazide diuretics produce an initial five to 10 percent elevation in total and LDL-cholesterol and a lesser increase in triglycerides. Treatment Effect on Lipids • The hyperlipidemic effect of thiazide diuretics is dose-dependent. • There is, for example, little or no effect on lipid metabolism with a daily dose of 12.5 mg of hydrochlorothiazide or its equivalent, a dose which may have as great an antihypertensive effect as higher doses. Treatment Effect on Lipids • The ACE inhibitors appear to have no important effect on plasma lipids and may minimize or prevent the rise in lipids induced by diuretic therapy (via an unknown mechanism). Treatment Effect on Lipids • The calcium channel blockers appear to have either a neutral or mildly beneficial effect on the lipid profile. Treatment Effects on Lipids • The effect of beta blockers on serum lipids varies with their pharmacologic characteristics, and may be more prominent among smokers. • Nonselective and beta-1-selective beta blockers have little effect on cholesterol levels but lead to an approximate 10 percent fall in cardioprotective HDL-cholesterol and, particularly with nonselective agents, a 20 to 40 percent rise in triglycerides. • In contrast, lipid levels are relatively unaffected by labetalol (a combined alphaand beta-blocker) and beta blockers with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity. Treatment Effect on Lipids • Newer beta blockers may have a more favorable metabolic profile; carvedilol, a combined nonselective beta and alpha-1 blocker, also prevents lipid peroxidation. • One study evaluated 45 patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and hypertension who were randomly assigned to therapy with metoprolol or carvedilol. Carvedilol was associated with a significantly greater fall in total cholesterol and lesser rise in triglycerides than metoprol. Specific Indications • Thiazide diuretics are particularly useful in black and elderly patients, while loop diuretics are typically used in patients with heart failure or other edematous state. Specific Indications • • • • • Beta blocker Resting tachycardia (usually reflecting an increase in beta-adrenergic tone) Heart failure due to diastolic dysfunction and some cases of systolic dysfunction Migraine headaches Glaucoma Those with a previous myocardial infarction or angina pectoris Specific Indications • • • • Contraindications to Beta Blocker Asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Severe peripheral vascular disease, Raynaud phenomenon Bradycardia, second or third degree heart block Hypoglycemia-prone diabetics in whom the early warning symptoms of hypoglycemia may be masked Specific Indications ACE inhibitors have a variety of advantages in the treatment of hypertension. • They are broadly effective in all patient groups (even in patients with relatively low plasma renin levels), lack the adverse lipid and glycemic effects of high doses of thiazides and ß-blockers, and have few toxic side effects. Specific Indications ACE inhibitors • Heart failure • Postmyocardial infarction • Diabetes mellitus • Proteinuric chronic renal disease, since these agents may slow the rate of disease progression Specific Indications • Underlying diseases that are relative indications for the use of an ARB are the same as those described above for ACE inhibitors, although an ACE inhibitor is most often used first. • Patients who cannot tolerate an ACE inhibitor (usually due to cough) can be switched to an ARB. Specific Indications • ARBs, like ACE inhibitors, also regress left ventricular hypertrophy more rapidly than beta blockers, and slow the rate of progression of diabetic nephropathy. Specific Indications • Long-acting calcium channel blockers share many of the advantages of the ACE inhibitors as vasodilatory agents. • They are effective antihypertensive agents that do not produce hyperlipidemia or insulin resistance and do not interfere with sympathetic function. • These agents are particularly effective in older patients or those with a low plasma renin activity Specific Indications • Calcium channel blockers tend to moderately increase sodium excretion and, in contrast to most other antihypertensive agents, their efficacy is usually not significantly enhanced by dietary salt restriction. • As a result, a calcium channel blocker may be particularly effective in hypertensive patients who do not comply with dietary salt restriction. Specific Indications • Calcium channel blockers may also be preferred in patients concurrently being treated with a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID). • The NSAIDs, by diminishing the production of vasodilator prostaglandins, often produce a moderate elevation in blood pressure in patients treated with most antihypertensive drugs; calcium channel blockers appear to be an exception, as their antihypertensive efficacy is not blunted in this setting. Specific Indications • In the large Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT), amlodipinebased therapy reduced blood pressure more than atenolol-based therapy. • This likely explains the greater prevention of cardiovascular events with the calcium channel blocker Specific Indications • There is also evidence that calcium channel blockers reduce the incidence of new-onset diabetes. A 2007 network meta-analysis reported that, compared with diuretics, the odds ratio for incident diabetes was 0.75 (95% CI of 0.62 to 0.90) for calcium channel blockers. Specific Indications • A calcium channel blocker should not be used as routine first line treatment of hypertension, except perhaps in black or elderly patients, and then in combination with a thiazide diuretic. Specific Indications • • • • • • Diseases that can also be treated by a calcium channel blocker include: Angina pectoris Recurrent supraventricular tachycardia (verapamil), Raynaud phenomenon (dihydropyridines) Migraine headaches Heart failure due to diastolic dysfunction Esophageal spasm Case 1 • A 21 year old student presents to the clinic for a complete physical exam for dental school. • Medical History is unremarkable • BP 162/90 • Physical Exam is normal • What do you do? Case 1 • BP 158/96 one month later in the clinic Home BP measurements: • 150/80 • 162/84 • 158/88 • 162/82 • 156/86 Case 1 • • • • • • How should you proceed? Labs ECG Life style modifications Home BP measurements Return to clinic in 6 months Case 1 • The patient returns 1 year later and the BP is 164/90 • The patient has gained 2 pounds. • Labs and ECG were normal. • What is the BP goal? • 140/90 Case 1 • • • • Reinforce lifestyle changes Motivate to control BP Start Medication Evaluate for secondary causes Case 2 • A 28 year old graduate student comes in for fatigue. • Recently had a URI. Still with nasal congestion. • Social Hx.-Binge drinker, occ tobacco, occ marijuana, lives with roommate • Family history negative Case 2 • BP 162/90 • HR 108, tachycardia • Pupils 5 mm. Nares red with clear rhinorrhea. • Rest of exam is normal. Case 2 Assessment • • • • • Hypertensive Tachycardia Mydriasis Rhinorrhea Poly substance use/? abuse Case 2 What to do? • Ask about other substance use, medications, secondary causes of hypertension • Get ECG • Discuss life style modification Case 2 • He is on a over the counter cold/sinus tablet • He admits to inhaling his roommates Ritalin over the past few days while studying for exams • ECG sinus tachy, otherwise normal Case 2 • Diagnosis is likely drug induced hypertension • Stop over the counter cold/sinus and Ritalin • Recheck BP in one week Case 2 • One week later BP 156/84 • Look for secondary causes Case 3 • A 19 year old student comes fin for a STI check • Patient nervous about recent sexual contact • Medical history unremarkable • BP 160/92 • Rest of exam is normal • STI labs drawn/ Patient counseled/ Patient will return in one week for results of labs Case 3 One week later • STI labs are negative • BP 148/96 • Ask the patient to return to clinic in one month Case 3 One month later • BP158/96 • ECG normal • Ask the patient to take BP at clinic several times over the next month Case 3 • • • • One month later: BP 133/84, 130/78, 132/82, 128/78 Diagnosis pre-hypertension, white coat hypertension Discuss life style changes RTC in one year Case 4 • A 56 year old student comes in for a PAP smear • ROS. Arthritis, type 2 diabetes controlled with diet and exercise • Other history is unremarkable • Takes ibuprofen daily for arthritis Case 4 • BP160/92, similar on previous 2 visits • Arthritis of hands • Rest of exam unremarkable Case 4 Assessment • • • • 56 year old Stage 2 hypertension Arthritis of hands Type 2 diabetes Case 4 • • • • • • What labs do you want? CBC Fasting lipid panel Chem 7 ECG UA Hgb A1c ( not a hypertension lab) Case 4 • • • • • • UA 1+ protein, 2+ glucose Cr 1.2 Now what? Start treatment for secondary hypertension ACE for kidney protection Avoid NSAID’s use acetaminophen Case 4 • • • • • Life style changes: DASH diet Weight reduction Exercise Low sodium diet Decrease ETOH Case 4 What is BP goal? • 130/80