Chapter 3: The Tavern and Anti-Social Behaviour

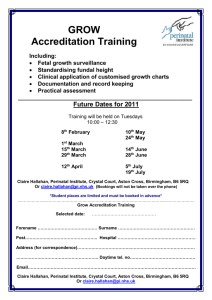

advertisement