Scientific and Technical Writing – Sample Project

advertisement

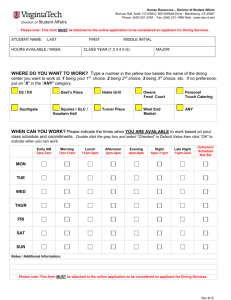

Michael Hsu Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey 30881 RPO WAY New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8808 April 27, 2011 Dean Robert M. Goodman Executive Dean of Agriculture and Natural Resources Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey 88 Lipman Drive New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8525 Dear Dean Goodman, I greatly appreciate your attendance at my oral presentation on April 14th. To this letter, I’ve attached a more in-depth analysis of issues covered in the food waste presentation, as well as a plan to further improve dining hall efficiency. I am sending this proposal to you because I am well aware of your dedication to maximizing the quality of and access to a superior education. As a student currently attending Rutgers University, these are goals that I would certainly like to see Rutgers working toward. By reducing the amount of waste at Rutgers University’s dining halls, the University can devote more money and resources toward your goals, while simultaneously minimizing meal plan prices and helping to solve the national food waste problem. Reducing the overall amount of food wasted reduces the amount of agriculture required to produce the nation’s food supply. As you surely know, intensive agriculture can have many far-reaching consequences with regards to the United States’ resources. The largest source of food waste comes from consumer plate waste and large foodservice industries – such as that of Rutgers University (Kantor, 1997). Currently, Rutgers University’s dining halls average over one ton of waste every day (EPA, 2009). My proposal will help to address that waste by first raising student awareness of the problems, then implementing a trial system at Busch Dining Hall to minimize the amount of plate waste by reducing the amount of food students take in one trip to the lines. This plan is supported by B.F. Skinner’s behavioral theory of reinforcement, along with the success of other universities’ attempts at resolving similar problems. Since you are a member of President McCormick’s council, you are in an ideal position to implement these changes in the dining system, and to help increase the overall quality of educational services here at Rutgers. If you have any questions, please feel free to contact me by phone at (347) 879-5472, or by e-mail at mshsu@eden.rutgers.edu. Thank you for your time, and I look forward to hearing back from you. Sincerely, Michael Hsu Minimizing Food Waste at Rutgers University Submitted by: Michael Hsu Submitted to: Robert M. Goodman Executive Dean of Agriculture and Natural Resources Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey 88 Lipman Drive New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8525 Prepared for: Elisheba Haqq-Stevens Scientific and Technical Writing (01:355:302:22) April 27, 2011 Abstract In the United States, about 40% of the national food supply is wasted. Wasted food that ends up in landfills can decompose to form methane, a greenhouse gas that is 25 times as effective as carbon dioxide in affecting global warming. Increased food consumption due to food waste also leads to increased agricultural land use for the production of wasted food. Coupled with poor agricultural practices, this leads to increased farm runoff. Farm runoff can cause the eutrophication of water bodies, causing an overall degradation of the water supply. 40% of the nation’s freshwater supply is used for irrigation in agriculture, meaning that about 16% of overall freshwater consumption is wasted in the production of discarded food. This occurs in a time when 36 out of 50 states are expecting water shortages by 2013 even in non-drought conditions, and most regions have already experienced shortages within the past five years. Food waste can occur throughout the food production process, but a study found the largest portion of food waste to be from foodservice and consumer plate waste. Rutgers dining is the third-largest student dining operation in the United States, but does not have any policies active in reducing student plate waste. This proposal uses the reinforcement theory of behavior first proposed by B.F. Skinner as a method to control voluntary decision-making, and bases its plan on successful solutions from three other universities seeking to curb their food waste problems. The University of Notre Dame used food drives to raise student awareness of the problem. The University of Maine adopted a tray-free dining policy. Ohio University experimented with sample stations at the dining halls. Following these examples, the proposal states that Rutgers University should adopt a similar awareness campaign, with additional campaigning through dining hall fliers and sections in the Daily Targum. The next two phases of the plan suggest the installation of sample stations and smaller trays at Busch Dining Hall. Busch Dining Hall is currently the most used dining hall by students, having undergone several renovations to accommodate for growing diner numbers, and analysis of the impacts of the plan on dining hall food waste can determine whether or not it should be further applied to other Rutgers campuses. i Table of Contents Abstract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . i Table of Contents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ii Table of Figures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .iii Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1-5 Consequences of Food Waste on a National Level . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-2 Sources of Waste . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2-3 Food Waste at Rutgers University . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3-5 Literature Review . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5-8 The Theory of Reinforcement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 The University of Notre Dame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5-6 The University of Maine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6-7 Ohio University . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..7-8 Plan for Rutgers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7-9 Education and Outreach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8-9 Installation of Sample Stations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9 Resizing Dining Trays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9-10 Budget . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10-11 Education and Outreach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 Installation of Sample Stations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 Resizing Dining Trays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11 Discussion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11 References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11-14 Appendices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15-16 Appendix A: Idealized diagram of current dining hall tray capacity . . . . . . . . . . .15 Appendix B: Idealized diagram of proposed dining hall tray capacity . . . . . . . . . 16 ii Table of Figures Figure 1: Percentage of food waste by sector . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3 Figure 2: Overview of Rutgers University’s monetary expenditures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 Figure 3: Reduction of food waste after sample implementation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7 iii Introduction Consequences of Food Waste on a National Level Currently, as much as forty percent of the nation’s entire yearly food supply is not consumed, but discarded to end up in landfills around the country. Food that ends up in landfills eventually decomposes and produces methane, a gas that is 25 times as effective as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere. This methane can result in the acceleration of global warming, a problem which is already of great concern to many scientists. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (2010) considers anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change to be “a serious challenge – one that could require new approaches and ways of thinking” (p. 2). Global warming can result in problems such as stronger storm systems and sea level rise, which can lead directly to the flooding of coastal communities. Ocean warming has been shown to result in problems such coral bleaching, damage to coral reefs that can prevent future generations from enjoying these beautiful aquatic ecosystems. Methane, however, is not the only gas that arises as a result of food waste. While it is the primary greenhouse gas of concern that arises directly from waste, the production and transportation of food also burns about 300 million barrels of oil a year, further adding to the elevated levels of carbon dioxide presently in the atmosphere (Hall, 2009). Greenhouse gas emissions from the oil used to produce food is only one of many problems tied to an increase in agricultural land use, an increase which is required to accommodate for the large amounts of waste that occur. As a result of food waste, the nation is producing about 60% more food than is actually needed to sustain the nation. The resulting increase in agriculture can result in various strains on the nation’s natural resources, such as local watershed quality and the nation’s overall freshwater supply. One of the major problems with current agricultural practices, and which is amplified by increased agricultural demand, is the presence of nutrient runoff from farms. Farm runoff, especially phosphorous-based compounds, effectively causes nutrient pollution in a body of water, a problem known as eutrophication. The increased quantity of nutrients present may be good for plants and other photosynthetic organisms initially, but the rapid proliferation of these organisms can eventually result in unusually low oxygen levels in a water body. The lowered oxygen levels can cause a die-off of environmentally sensitive fish and other animals which depend on that particular source of water, resulting in the loss of biodiversity, overall degradation of the water supply, and damage that can last for centuries (The Associated Press, 2011). According to the EPA (2005), farm runoff is the leading source of impairments to rivers and lakes. These negative effects are not restricted to only affecting the natural environment. Communities may depend on water bodies for recreational use, and eutrophication of those locations can have adverse effects on the ability of humans to enjoy the natural scenery. Certain algal species produce toxins, and can have undesirable effects on people seeking to use the area. As an additional stress to the nation’s water supply, irrigation used for agriculture is the single largest sector of freshwater use in the United States (Hutson, 2004). It is simply unacceptable that nearly half of the water used in agriculture is lost in the production of wasted food, in a time when the United States is facing an ever-growing population and demand for water. At least 36 states are anticipating some degree of water shortages by 2013, even under non-drought conditions, and in the last five years, nearly every region of the country has experienced water 1 shortages (EPA, 2008). It is, therefore, imperative that water be saved where it is possible, and reducing the amount of food that the nation wastes can help to provide this support. Sources of Waste In order to begin tackling the issue of food waste, it is important to know where the main sources of food waste lie. Throughout the production and delivery of food, there are many opportunities for waste. Even before the food is harvested and processed, inclement weather can cause losses at the production level. Pest infestations and crop diseases can devastate a harvest, especially when the field in question is fairly uniform, allowing diseases to spread quickly. Severe weather, such as heavy rain or hail, may cause damage to crops in the field, and lack of precipitation can also cause losses. Some food may also be lost during harvesting. In the modern age, many fields are now machine-harvested. Although mechanizing the harvest process certainly saves time and money, machines are not quite as discerning about the crops being harvested as humans might be. Sometimes, not all edible portions of a crop are harvested, and sometimes, crops that would not make it through inspection do get harvested. Pests getting into the food supply remain a problem during storage, much like they were during production, and mold and other microorganisms can damage stores of food. Even without the many pests that may damage food supplies, there is a general deterioration of food quality over time. Food that does not meet the safety standards of the EPA gets tossed out as an acceptable loss (waste) of food. At the retail level, perfectly edible food is still often discarded due to suboptimal appearance, often bypassing charitable organizations to be delivered directly to landfills. Still more safe food is discarded, once the food’s “sell by” or expiration date has passed, though food often remains safe within a few weeks afterward. From a business perspective, this shows consumers that the business is dedicated to providing quality products. However, from a waste management perspective, this produces even more unnecessary waste. The discarded food often does not find its way to the needy, but is ultimately thrown into landfills (Kantor, 1997). 2 The United States Food Supply Retail Food Loss 2% Figure 1: Percentage of food waste by sector (Kantor 1997). Foodservice and Consumer Food Loss 25% Not Included 73% Despite the myriad of opportunities where food can be wasted, however, a study performed by the United States Department of Agriculture showed that the single largest source of food waste came from consumers and food services (Figure 1). Much of this comes from food services preparing more food than necessary, and from plate waste – food that is taken, but not consumed. That is where adopting a policy of minimizing food waste at Rutgers University can help. Food Waste at Rutgers University Rutgers University currently runs the third largest student dining operation in the country, serving over 3.3 million meals each year (About us, 2011). This puts the University at a unique position to make a major difference in the area of food waste; by demonstrating the ability to reduce food waste on such large-scale dining operations, it can set a leading example for many other universities to follow. Unfortunately, as of right now, Rutgers does not have any programs specifically directed toward reducing student plate waste at the dining halls. 3 Figure 2: Overview of Rutgers University’s monetary expenditures (Rutgers, 2010) Of its 2 billion dollar annual budget, the university spends close to 14% of it on auxiliary enterprises, including dining services (Figure 2). By cutting back on the amount of food wasted by students – that is, the amount of food taken from the dining hall, but not consumed and returned as plate waste – the university can devote more money toward the education of its students. Currently, Rutgers University wastes an average of 1.125 tons of food (measured in dry weight, after pulping) per day. This waste can come from the aforementioned plate waste, as well as the discarding of excess prepared food after a meal period. On occasion, members of the dining hall staff will make one last effort to distribute leftover baked goods to students, but normally, these efforts will only cut back on a few slices of cake wasted per dining hall. Some efforts have been made toward recycling existing food scraps, and the remnants are reused as food scraps for local pig farmers (Department of Environmental Protection, 2009). However, this ultimately still comes at a cost to the University, at about $30 per ton of waste; the money used to purchase the food and the energy invested in cooking and preparing food for student dining is lost as well. The cost that food waste bears on the University will eventually trickle down to become a burden on students. Currently, Rutgers University requires all students living on campus to have a minimum meal plan. As a result, the cost of a meal plan can have a direct effect on the cost of staying at the University. Not only will that result in complaints from current students and their parents, but higher costs for on-campus students may also result in deterring students who may otherwise be interested in attending Rutgers University. By reducing the amount of food wasted at the dining halls, the cost of meal plans can be kept to a minimum, which, in turn, will help to minimize housing costs. While many universities have already taken steps toward raising student awareness regarding the problem of food waste, Rutgers University has shown little to no initiative in this regard, save for the minor acknowledgement of the problem by Dining Services. The general lack of information on the subject results in a lack of student awareness that there is a problem to be corrected. One 4 poll found that out of every ten people, nine simply were not aware of just how much food they wasted (The Telegraph, 2008). This suggests that one of the biggest causes of food waste on the local level is simply the lack of awareness of the problem. Students cannot be more considerate of the amount of food they are wasting if they do not realize that there is a problem in the first place. Educating students on the dangers of food waste has been one of the approaches toward reducing food waste at university dining halls. Literature Review The Theory of Reinforcement The concept of reducing food waste is not new, and many universities have already made efforts toward tackling the problem. There have been many different approaches, one of the most common being simply educating students regarding the problem, but between them, there is one thing in common. Each plan has been geared toward encouraging a particular action – encouraging more conservative dining hall choices in order to reduce food waste. The goal of increasing the likelihood of a particular behavior falls under the domain of reinforcement theory. Reinforcement is a behavioral theory which states that the likelihood of a particular behavior can be increased by providing a “response” to that behavior. A response can be the addition of a favorable stimulus, called positive reinforcement, or the removal of an unfavorable stimulus, termed negative reinforcement. The theory was first proposed by B.F. Skinner through his work with what he termed an operant conditioning chamber. In an operant conditioning chamber (now colloquially known as a Skinner Box), the main feature of interest is a lever or bar of some sort, which will trigger some sort of response when pressed. In positive reinforcement, the lever will release a food pellet upon being pressed. When a hungry rat is placed within the chamber, its lever presses become more frequent as it discovers that pressing the lever will produce a food pellet reward – the response, which leads to positive reinforcement of the lever-pressing behavior. In negative reinforcement, there is one additional feature in the box: the presence of an electrified floor grid, which causes discomfort for the rat. Pressing the lever will remove the stimulus, considered an aversive or unwanted stimulus. This quickly reinforces the behavior of pressing the lever more frequently in order to avoid the electric current. Similar blind studies have shown that human behavior is also much affected by conditioned reinforcement (Leslie 1999). For humans, money is a fairly generalized conditioned reinforcer, but, in application to the subject of food waste, the idea that an individual is doing something meaningful may be one as well. If someone is aware that he or she is doing something perceived to be “good”, then it will result in a general positive feeling that acts as a reinforcer on its own, promoting the repetition of that action. The University of Notre Dame The University of Notre Dame took advantage of the idea that knowledge and pride in doing something meaningful could be a reinforcer, and held food drives to raise student awareness of the problems associated with food waste. Much like Rutgers University, the University of Notre Dame (ND) wastes a little over a ton of food each day. In order to help reduce all of this waste, the university held food drives to educate students about the issues surrounding food waste. These food drives presented the idea that doing something as simple as being more thoughtful in regards to how much food a student took could help to solve an issue with problems that stretch across many different fields. ND also chose to adopt a more conventional approach with reinforcement: rewarding students for turning in clean plates. During waste-free Wednesdays, 5 students who presented a clean plate with no wasted leftovers during dinner would be entered into a raffle to win 100 “Flex Points” (Doyle, 2010). The system of flex points is reminiscent of Rutgers’ own RU Express policy. The points can be traded for food and beverage items offered in campus restaurants, express units, and convenience stores (University of Notre Dame, 2011). Waste-free Wednesdays provided two different versions of positive reinforcement. The first type comes from the awareness that the University spread amongst its students, as previously described. The second type is provided for by the subsequent raffle. Students who minimize their food waste receive a positive stimulus in the form of a chance to win Flex Points, and an opportunity to dine at local restaurants for free. By providing the appropriate background information, as well as an incentive for students to take the steps toward reducing food waste, the university greatly encourages its diners to adopt less wasteful eating habits. However, waste-free Wednesdays pose additional costs, in the additional manpower required to check plate cleanliness on Wednesdays, as well as the raffle reward. In addition, if there are many students eating dinner at the dining hall simultaneously, this can lead to congestion at the exit as students ensure their personal information is entered correctly for the raffle. An additional staff member would have to be on duty during waste-free Wednesdays in order to ensure orderly dining hall flow. Congestion can ultimately end up discouraging some busy students from participating in the program. Given the large size of Rutgers University’s Dining Services, such a large-scale reward system would be difficult to implement efficiently. However, the idea of raising awareness through food drives is something that Rutgers should have the ability to adopt, which will be discussed later in this proposal. The University of Maine Despite the presence of such education and positive reinforcement, students may still be lax in watching what they take from the dining halls. While reinforcement is meant to promote the frequency of a particular behavior, a particular response may not be a universal reinforcer. The property of a stimulus being a reinforcer is not inherent in the stimulus itself, but rather, depends upon the state of the organism and its environment at the time the stimulus is provided (Leslie 1999). Students may feel that they are unlikely to win random dining hall raffles, or find themselves simply unable to finish all of the food they take. For those students, intrinsic motivation alone is not enough to ensure an effort to reduce food waste. In order to encourage such students to be more selective in the foods that they choose to take, several dining halls have chosen to adopt a more dramatic change in their food service policies – removing trays. This sets up a situation of negative reinforcement, where the desired behavior removes the unwanted stimulus of having difficulty bringing food back to the table. In a study at the University of Maine at Farmington, Aramark, trayless dining was found to have reduced food waste by as much as 25 to 30 percent (Davis, 2008). The study also found that, in addition to the primary goals of reducing food waste, trayless dining also saved the university close to 300,000 gallons of water and $57,000 worth of resources, which would otherwise have gone into cleaning the dining hall trays. In tray-free dining, the desired behavior is to have students take less food back to the table at once, so they do not over-anticipate the amount of food they will actually eat. When students do carry back less food, which is the desired behavior, a negative stimulus – in this case, difficulty in retrieving food – is removed, thus reinforcing the desired action. Since this is done on a continuous basis, each time a student brings back smaller portions will further reinforce the action. A downside of this policy is that it can cause unintended difficulties for students, such as the inability to comfortably carry back utensils, plates, and drinks to their seats 6 without making several extra trips. However, despite such inconveniences, a poll at the College of William and Mary – another institution of higher education adopting a similar trayless policy – showed that students had an overall positive response to the idea, despite the additional challenges they would face in getting their food (Davis, 2008). When made aware of the resource savings that would come about as a result of trayless dining, seventy-five percent of the students were willing to adopt the trayless policy. Another practical downside is the higher tendency of messy tables, and the potential requirement of another worker to maintain cleanliness of the dining halls. Students will not wish to dine at dirty tables. Normally, with trays, any accidentally spills would be caught in the tray, and carried off along with it to leave a clean table. However, without trays, any spills will be on the tables directly, and will remain there until cleaned off. This is worsened by the possibility that, due to the plate limitation, students will be more likely to pile more food onto their trays, increasing the likelihood of food spillage. Thus, while the waste reduction and resource savings are definitely clear benefits of adopting a tray-free policy, there are still some major drawbacks with having no trays at all. This leads to the conclusion that limiting the amount of food students bring back will reduce food waste, but something must be done to maintain dining hall cleanliness. Ohio University Some students, however, may object to such a kind of limiting policy on the grounds of food taste. While Rutgers does not have particularly distasteful food, there is certainly a large variety. This large variety is very likely to have something that appeals to every student; however, in the same vein, the large variety is likely to have at least something that is unappetizing to various students. This leads to an unfortunate problem where students will simply take a portion of several assorted things on the menu, some of which they will invariably find not to their liking and end up discarding. The portion sizes served on the food lines are large enough for a full meal, and so amounts to a significant amount of loss when students decide that the food they took does not quite suit their tastes. One idea, then, is to provide a system that provides positive reinforcement where careful consideration of food intake provides a positive stimulus of convenience, as opposed to one with negative reinforcement of removing inconvenience. Ohio University has adopted one such plan, by providing sample size portions for their students (Ohio University, n.d.). In a pilot study done by the university, giving students samples of the foods on display resulted in a noticeable decline in the amount of waste produced per student (Figure 3). Average food waste per student (oz/person) 5.8 5.6 5.4 Figure 3: Reduction in food waste after sample implementation (Ohio University). 5.2 5 4.8 4.6 4.4 4.2 Baseline Baseline Average Samples Theme 1 2 Dinner The sample size portions enable students to taste-test the various foods available during a meal period. As a result, when they go 7 to pick out their meal, students will not waste food sampling everything that may look somewhat appealing, but can pick out specific items that they will be certain to enjoy. Reinforcement can be seen here through a positive stimulus in response to using the sample stations. Students who choose to sample foods before they go to the main line can avoid taking foods which they would consider undesirable. In turn, being able to pick out specific foods of interest allows the students to carry less food back to the table, providing the positive stimulus of added convenience. Sample stations can also serve to reduce congestion at the actual food lines, where students will not have to hover about for a few moments before finally deciding on what to get. Instead, it encourages faster movement through the dining hall, where students can simply grab a few bitesized samples before continuing on their way. On the downside, providing sample size portions requires additional dining hall space, which may cause some degree of crowding at dining tables. However, Rutgers does not have small dining halls, and often has specialized tables out during event meals for specific items. These event meals tend to have even more people than usual dining nights, yet the amount of students in the dining halls during these events can still be considered low enough for comfort. Having them out on regular meal periods, then, should not impose too greatly on dining room flow. Furthermore, sample size portions can work remarkably well with a method of reducing the amount of food taken, such as through tray-free dining. Trayfree dining reduces the amount of food that a student is able to take, while sample size portions reduce the amount of food that a student will want to take. Thus, implementing both ideas in the plan can provide a synergistic effect not present in either one alone. Plan for Rutgers Education and Outreach Before Rutgers University implements facets of the approaches taken by the University of Maine and Oho University, however, it should first seek to raise student awareness regarding the problem, in a way similar to what the University of Notre Dame did. Rutgers already has an established program for running food drives, through the Rutgers Against Hunger (RAH) program. RAH is a well-established university-wide initiative that, among other tasks, seeks to address issues such as food insecurity. Currently, it has close to 52,000 Rutgers students, 9,000 faculty members, and 360,000 alumni working toward making a difference. RAH regularly hosts food drives to distribute food to charitable organizations. Keeping in mind its current status in Rutgers University, adding a factor of education regarding food waste during their food drives can have a great positive impact on reducing the amount of food waste produced at Rutgers University. This plan proposes a monthly food drive at each of the main campus centers on each Rutgers campus. Student volunteers interested in working with RAH’s campaign will be asked to encourage food donations, as per the goals of RAH, but will also be tasked with a brief poster presentation regarding the problems of food waste both at Rutgers University and in the nation. The monthly presentations will help to spread and maintain awareness of the food waste problem. However, in order to ensure that the message reaches those students who attend the dining halls, but might not have the time to stop and pay attention to the presentations, each month, alongside the presentation, small fliers will be distributed throughout the dining hall tables. Currently, there is a weekly Monday newsletter concerning various types of dining advice, provided by Dining Services in the same manner. The sheets of paper are printed and laid out on dining tables for students to read as they eat – a good strategy, as many students may enjoy having something to do along with their meal. This will be replicated with the food waste fliers. In order to avoid conflict with the main newsletter, the fliers will be distributed on the first 8 Wednesday of each month, instead of on Mondays. Furthermore, an insert regarding food waste at Rutgers, and the statistics on how successful the program is proving to be can be printed in the Daily Targum once near the middle of the semester, after mid-terms. Providing frequent updates on the University’s success will help students to maintain a positive outlook on the waste reduction efforts, either by showing that waste has been declining, or further encouraging students to be mindful of their eating habits. Between the fliers, the awareness food drives, and the Targum inserts, a high level of student awareness regarding food waste problems should be established, both beginning the process of reducing food waste, and setting the ground for the next phases of the plan. Installation of Sample Stations Given the large size of Rutgers University’s dining service, the second and third phases of the plan will be restricted to Busch Dining Hall, which is the most populous dining hall at Rutgers, and has recently undergone renovation in order to accommodate for more students. Three gasheated trolleys containing prepared, bite-sized food samples will be provided at the wall across from the utensil and tray carts. As these stations will be among the first locations that students pass on their way to getting food, it will be easy for students to simply take a few samples and determine what they like before moving on to the main lines. Considering the relative efficiency of taking a sample, compared with gathering an entire meal’s worth of food, three trolleys should be enough to minimize traffic at the sample stations. Service at Busch Dining Hall is concentrated at several main food locations: the salad bar, the pasta cook-to-order line, the deli line, the hot food line, and a special cooking line. Of all of these, the only station which will find significant use of samples will be the hot food line, and Busch Dining Hall is able to run relatively efficiently even with just the one line. Therefore, three sample stations should be more than enough to ensure a smooth procession through the dining hall. Resizing Dining Trays Once sample stations have been well-established, the plan can proceed to phase three during the second semester of the school year: adopting smaller trays. While simply switching to a tray-free policy in the way the University of Maine did could further save the University in water usage and energy costs, the large size of the dining hall makes this impractical. The problem with a tray-free policy, mentioned in the paradigm section, is the greater amount of mess expected on the tables. While this may be easier to clean in small areas, the size of the dining hall would require significantly more manpower to ensure clear tables. By switching to smaller trays, the limitation on the amount of food able to be carried back remains in place, but the issue of food spillage is also minimized. Currently, as illustrated in Appendix B, the dining hall trays can hold about two plates, a bowl, a cup, and utensils comfortably. The proposed trays, illustrated in Appendix C, will limit this by about one plate’s worth of food. The plan’s success can be measured by carefully weighing the amount of waste produced by Busch Dining Hall both before and after all three stages have been implemented. Should a significant decline in food waste be measured, a similar policy can be applied to the University’s other dining halls – with a notable exception of Brower Commons. Unlike the other three dining halls, Brower does not use a conveyor belt system to deliver dishes back to the kitchen to be washed; instead, it uses a set of tower trolleys, where trays are placed before being moved into the kitchen in large groups. Without a large overhaul of Brower’s cleanup system, the use of 9 smaller trays cannot be practically instituted in the dining hall. Sample stations are still a viable action, but changing the established system is beyond the scope of this plan. Budget Education and Outreach Each presentation will require 1 tri-fold poster board, 10 sheets of paper for poster design, and 100 fliers to be handed out. In addition, since education will be done alongside a RAH food drive campaign, two cardboard boxes will be present to collect food donations. As the plan proposes a monthly food drive across all four Rutgers campuses, there will be 32 individual presentations (4 campuses, and 8 months in the school year) throughout each school year. These stations will be manned by student volunteers who are willing to work with RAH’s mission for several hours each month throughout the school year, so personnel should not have an impact on the cost of this phase. Item Tri-fold poster board Color-printed paper Cardboard box (24”x12”x8”) Total: $1,279.68 Cost $8.49 Staples $0.25 Rutgers University $2.00 Amazon Quantity 32 Subtotal $271.68 3520 $880.00 64 $128.00 Installation of Sample Stations For the purposes of this plan, sample stations will be restricted to Busch Dining Hall, currently the most populous campus dining hall at Rutgers. The performance of the implementation at Busch will be useful in determining whether or not a similar system should be instituted in other dining halls as well. This will require three gas-heated sample stations, and one additional personnel to monitor the trolleys to keep them stocked with samples. Item Gas-heated trolley Dining services worker Total: $14,195.87 Cost Quantity $1,060.29 3 Instawares Restaurant Supply $10,925 /yr 1 Collegiate Times Subtotal $3,270.87 $10,925.00 10 Resizing Dining Trays About 1000 14-inch by 10-inch trays will replace the trays currently in place at Busch Dining Hall. This can be expanded for other dining halls in the future if the plan proves successful. No additional service costs should be necessary in this phase, as it is meant to seamlessly replace the existing tray system. Item 10”x14” food trays Total: $2,352.00 Cost $23.52 /dozen Quantity 200 (dozen) Subtotal $4,704.00 The overall cost of all three parts of the plan comes out to be approximately $20,197.55. Discussion A small commitment to waste reduction here at Rutgers University will have positive impacts on its overall sustainability, its monetary expenditures, and its accessibility to students. Food waste is intricately tied with many different problems that cover a huge range of scales, from global warming on the global level, resource use on a national level, and monetary expenditure on a local level. By adopting a policy based on the idea of reinforcement, Rutgers University can work with its students to reduce food waste at the dining halls. While the scope of the main portion of the plan, the installation of sample stations and smaller trays, is currently limited to Busch campus, evaluating waste totals at Busch Dining Hall before and after implementation can help to confirm the success of the plan. If there is a significant reduction in waste, then Rutgers University can apply the plan to dining halls on its remaining campuses, ultimately saving on energy and food costs in the long term, and helping to address the national food waste issue. 11 References About Rutgers against hunger. (2009). Informally published manuscript, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey. Retrieved from http://rah.rutgers.edu/about.shtml About us. (2011). Informally published manuscript, Rutgers Dining Services, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey. Retrieved from http://food.rutgers.edu/about-us Davis, A. (2008, October 25). Eliminating college dining hall trays cuts water, food waste. Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/OnCampus/story?id=6087767&page=1 Doyle, M. (2010). Nd works to reduce food waste. Informally published manuscript, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana. Retrieved from http://www.ndsmcobserver.com/news/nd-works-to-reduce-food-waste-1.1745497 Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Wastewater Management. (2008). Water supply and use in the united states (EPA-832-F-06-006). Washington, DC: Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/WaterSense/pubs/supply.html Farm runoff worse than thought, study says. (2005, June 14). The Associated Press. Retrieved from http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/8214501/ns/us_news-environment/ Graduate student and non-resident undergraduate meal plans. (2011). Unpublished manuscript, Food Services, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana. Retrieved from http://food.nd.edu/meal-planscard-services/grad-student-and-non-resident-off-campusundergraduate/ Hall, K.D., Guo, J., Dore, M., & Chow, C.C. (2009). The progressive increase of food waste in america and its environmental impact. PLoS ONE, 4(11), Retrieved from http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0007940 12 Hutson, S.S., Barber, N.L., Kenny, J.F., Linsey, K.S., & Lumia, D.S. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. (2004). Estiamted use of water in the united states in 2000. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services. Kantor, L.S., Lipton, K., Manchester, A., & Oliveira, V. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. (1997). Foodreview: from farm to table: the economics of food safety; estimating and addressing america's food losses (FoodReview No. (FR-20-1)). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Ohio University. (n.d.). Food waste audits. Retrieved from http://www.ohio.edu/sustainability/FoodWasteAudits.htm Rutgers expenditures. (2010). Informally published manuscript, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey. Retrieved from http://budgetfacts.rutgers.edu/pdf/expend_pie.pdf United States Department of Environmental Protection, (2009). Feeding animals - the buisiness solution to food scraps (EPA 530-F-09-022). Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/osw/conserve/materials/organics/food/success/rutgers.pdf United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Air and Radiation. (2010). Climate change science facts (EPA 430-F-10-002). Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/downloads/Climate_Change_Science_Facts.pdf United States Department of Environmental Protection, Office of Wetlands, Oceans, and Watersheds. (2005). Protecting water quality from agricultural runoff (EPA 841-F-05001). Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/owow/NPS/Ag_Runoff_Fact_Sheet.pdf 13 Uk bins £8bn of food each year, study claims. (2008, January 14). The Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/earthnews/3321664/UK-bins-8bn-of-food-eachyear-study-claims.html 14 Appendix A: Idealized diagram of current dining hall tray capacity. Not actual size. Rectangular regions represent the full tray size (note that the actual tray has rounded corners) and the size of the flat portion of the base, which has dimensions of 12 x 16 inches. Large plates are approximately 9 inches in overall diameter, with a base measured to the outer top rim of about 8 inches; these plates may be pushed a little further up the sides of the tray to accommodate for other serving ware. The cup (small circle) is 2.5 inches in diameter, while the bowl (medium-sized circle) has an overall diameter of 6 inches, but the base is only about half that size – approximately 3.5 inches. 15 Appendix B: Idealized diagram of proposed dining hall tray capacity Not actual size. Dimensions of glassware are the same as in Appendix B. This diagram shows that, despite the smaller tray size, it is still possible to hold enough food for a meal on the tray – the only difference is the elimination of one large plate. The overall tray size is two inches smaller on each edge: 10 x 14 inches. 16