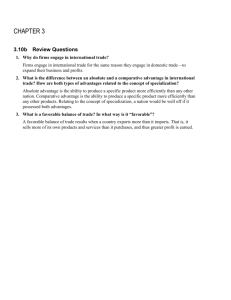

text-book-_chapter_11

advertisement