here - Identity

advertisement

Methodological naturalism and

the identity of practical reasons

Marko Jurjako

University of Rijeka

Structure of the talk

• The role of methodological naturalism

1. Theories of practical reasons

2. Identity of reasons (norms of rationality)

3. Explaining normative intuitions

Philosophical naturalism

• Two kinds of philosophical naturalism

1. Metaphysical naturalism

It is “concerned with the contents of reality,

asserting that reality has no place for

‘supernatural’ or other ‘spooky’ kinds of entity.”

(Papineau 2007)

1.1 Moral naturalists “concentrate on finding the

place of value and obligation in the world of

facts as revealed by science.” (Harman 2000,

79)

2. Methodological naturalism:

“[M]ethodological component is concerned with the

ways of investigating reality, and claims some kind of

general authority for the scientific method. [...]

Methodological naturalists see philosophy and science

as engaged in essentially the same enterprise,

pursuing similar ends and using similar methods.

Methodological anti-naturalists see philosophy as

disjoint from science, with distinct ends and

methods.” (Papineau 2007)

Why methodological naturalism?

• Platitudes about science: science is the most

successful human enterprise for explaining the

natural phenomena …

• professional necessity:

“It is not possible to step far into the ethics

literature without stubbing one’s toe on empirical

claims. (…) There are just too many places where

answers to important ethical questions require—

and have very often presupposed—answers to

empirical questions. “(Doris & Stich 2010, 112)

Ontological constraint

• Naturalistic constraints make certain robust

forms of normative realism implausible

• A Darwinian Dilemma for a Normative Realist

(Street 2006)

Theories of practical reasons

1. Dispositional-functional theory

– X has a reason to if and only if there is a sound

or rational deliberative route from X’s current

mental states to X’s -ing (see e.g. Wedgwood

2011, 180; Williams 1981; 1995)

– an agent (…) has a reason to Φ in C, if and only if,

if she were fully rational, she would desire that

she Φs in C.” (Smith 2004, 20)

Theories of practical reasons

2. Reasons as normative explanations

– Reason for you to is an explanation why you ought to

(Broome 2004, 35)

3. Reasons as evidence

– Necessarily, a fact F is a reason for an agent A to φ iff F is

evidence that A ought to φ (where φ is either a belief or an

action) [Kearns & Star 2009, 216]

4. Reason as a primitive concept

– Reason is a fact that counts in favor of holding some

attitude … (Parfit 2011, Scanlon 1998, Skorupski 2010)

Methodological naturalism

• favors dispositional theories of reasons

• practical reasons determine choice

rational choice theory, decision theory …

C={pi Bpi}, D={piVpi}, (C,D)= D*

• David Lewis, Michael Smith … reflections on

decision theory

Methodological naturalism

• favors dispositional theories of reasons

• practical reasons determine choice

rational choice theory, decision theory …

C={pi Bpi}, D={piVpi}, (C,D)= D*

• David Lewis, Michael Smith … reflections on

decision theory

Dispositional theories

• Reasons are determined by the norms that

govern agent’s responses to certain facts

• rational norms: core norms that every rational

agent will obey

• Which norms are rational norms?

• How to answer that question?

• Are there some substantive reasons that will

be shared by all rational agents?

• Are moral reasons those reasons?

Identity of reasons (norms of

rationality)

• Universality of practical reasons - every

possible rational being will have some reason

to obey substantive requirements e.g. moral

rules

• Relativity of practical reasons – practical

reasons are contingent on values, preferences,

personal projects, … of a deliberating subject

(Harman 2000, Williams 1981)

Moral demands and practical reasons

• ‘’To say that there is a moral law that ‘applies

to everyone’ is, I hereby stipulate, to say that

everyone has sufficient reasons to follow that

law.’’ (Harman, 2000, 84)

Moral relativism

• ‘’Moral relativism denies that there are

universal basic moral demands, and says

different people are subject to different basic

moral demands depending on the social

customs, practices, conventions, values, and

principles that they accept.’’ (Harman 2000,

85)

Harman’s naturalism

• Different approaches for doing moral philosophy

can be differentiated by their attitude towards

science (Harman 2000, 79).

• Moral naturalists “concentrate on finding the

place of value and obligation in the world of facts

as revealed by science.” (ibid.)

Basic structure of the argument

• Moral absolutism (MA) everyone has a

sufficient reason to obey certain basic moral

demands (SR)

• Methodological naturalism (MN) ~(SR)

∴

• ~(MA & MN)

Harman’s argument

• Proposed moral requirement: there is a basic moral

prohibition on causing harm or injury to other people

• First Premise: “if a person does not intend to do

something and that is not because he or she has

failed in some empirically discoverable way to

reason to a decision to do that thing then according

to the naturalist the person cannot have a sufficient

reason to do that thing.” (Harman 2000, 86)

-

inattention, lack of time, failure to consider or appreciate certain arguments,

ignorance of certain available evidence, an error in reasoning, some sort of

irrationality or unreasonableness, or weakness of will

• Second Premise: “there are people, such as certain

professional criminals, who do not act in accordance

with an alleged requirement not to harm or injure

others, where this is not due to any of these failings.”

(Harman 2000, 87)

• Conclusion: moral absolutism is false if naturalistic

characterization of reasons is taken for granted

First premise: structure of reasons

• Person A has sufficient reason to Φ iff there is

warranted reasoning that person A could perform

that would lead A to decide to do Φ (Harman

2000, 86)

• Naturalistic constraint:

– if A fails to respond to a reason that she has then

there must be some empirical explanation of that

failure

– if A does not intend to do Φ and that is not because of

some empirically discoverable failure then A does not

have a reason to Φ

Second premise

• description of a type of person that is not

irrational (at least not in any empirically

discoverable way) but does not respond to

moral requirements

• If premise 2 is true then not everyone has a

sufficient reason to obey the same basic

(moral) requirements

• Therefore, naturalistic constraint favors

relativity of practical reasons

Undermining the argument

• M. Smith (2012)

– Naturalistic constraint is not relevant for the

argument

• Person A has sufficient reason to do Φ iff

there is warranted reasoning that person A

could perform that would lead A to decide to

do Φ

Undermining the argument

• M. Smith (2012)

– Naturalistic constraint is not relevant for the

argument

• Person A has sufficient reason to do Φ iff

there is warranted reasoning that person A

could perform that would lead A to decide to

do Φ

What constitutes warranted

reasoning?

What are the principles of

warranted reasoning?

Principles of rationality

• MEANS-ENDS+

– rationality requires one to possess true and evidentially wellsupported beliefs, and complete and transitive preferences

• UNIVERSALIZATION+

–

Kant’s Formula of Humanity

• REASONS+

– intrinsic nature of harm and injury provide any rational

being with a reason to desire not to be harmed and

injured and not to harm or injure anyone else

Examples

• Principles of rationality

– Reason requires (RR)

• ME: RR(If someone has an intrinsic desire that p and a

belief that he can bring about p by bringing about q,

then he has an instrumental desire that he brings

about q)

• UNI: RR(If someone has an intrinsic desire that p, then

either p itself is suitably universal, or satisfying the

desire that p is consistent with satisfying desires whose

contents are themselves suitably universal)

• INT: RR(People desire not to be harmed or injured and

not to harm and injure others) [cf. Smith 2009]

How to determine the correct

principles of rationality?

Michael Smith

• validity of rational principles is decided on a priori

grounds (2012, 238-239)

• “[A] characterization of rationality and reasonableness

will follow from a spelling out of everything that we can

know a priori about belief and desire.” (239)

• “[N]aturalism is thereby shown to be completely

irrelevant to the issue that divides them [absolutists] from

their relativist opponents. What divides them is what we

can say a priori about belief and desire. This is what

relativists and absolutists really disagree about.” (240)

Full-blown naturalism

• Methodological naturalism

• “[M]ethodological component is concerned with the ways of

investigating reality, and claims some kind of general authority

for the scientific method. [...] Methodological naturalists see

philosophy and science as engaged in essentially the same

enterprise, pursuing similar ends and using similar methods.”

(Papineau 2007)

• proper characterization of rationality defers to

the scientific concept of rationality

– reasoning sanctioned by our best scientific theories

(Colyvan 2009), concept of rationality that is used in

science …

Principles of rationality in science

• Instrumental and epistemic rationality

(decision theory, game theory, probability

theory) MEANS-ENDS+

• “Reason is wholly instrumental. It cannot tell

us where to go; at best it can tell us how to

get there. It is a gun for hire that can be

employed in the service of any goals we have,

good or bad.” (Simon 1983, 7-8, in Over 2004,

5)

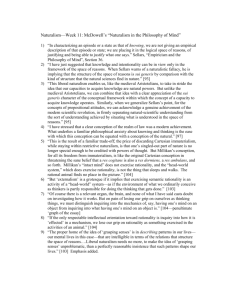

Rationality and mechanisms

Functional

specification of an

agent (norms of

rationality)

To do list

Figure adapted from

Hendricks (2006,

138)

Norms of rationality

Contingency of reasons

Contingent reasons

3. Normative intuitions

• We have many intuitions about reasons that

cannot be captured by instrumental

conception of rationality

– intuitively many intrinsic desires and goals seem

irrational

• Devotion to counting blades of grass seems irrational

• future Tuesday indifference

• agreeing to experience great amount of pain later in

order to avoid little pain now … (Parfit 2011)

Programmatic response

• There are no mind-independent normative facts

that provide reasons for action – our normative

intuitions are shaped and influenced by

evolutionary (and cultural) history (Street 2008)

• These intuitions indicate situations that decrease

fitness, and expose preferences that do not track

fitness resources (Sterelny 2012)

• Interesting research question is why we have

intuitions and deliver judgments about reasons of

third-parties (persons) who do not affect our

well-being (fitness or even utility) directly?

References

•

•

Broome, J. (2004). ''Reasons.'’ In Reason and Value: Themes from the Moral Philosophy of Joseph Raz, J. Wallace,

M. Smith, S. Scheffler i P. Pettit, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 28–55.

Colyvan, (2009). Naturalizing Normativity. In Conceptual Analysis and Philosophical Naturalism, D. BraddonMitchell and R. Nola (eds.), A Bradford book, Cambridge: MIT Press, 303-313.

•

Doris, J., M. & Stich, S., P. (2012). As a Matter of Fact: Empirical Perspectives on Ethics. Chapter 11 in Stephen Stich's

Collected Papers, Volume 2: Knowledge, Rationality, and Morality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

•

Harman, G. (2000). Is There a Single True Morality. in his Explaining Value and Other Essays in Moral Philosophy,

Oxford: Clarendon Press, 77-99.

•

•

•

Hendricks, V., F. (2006). Mainstream and Formal Epistemology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kearns, S. & Star, D. (2009). "Reasons as Evidence." Oxford Studies in Metaethics 4, 215-242.

Parfit, D. (2011). On What Matters, vol. 1 & 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

•

•

Railton, P. (1986). Moral Realism. The Philosophical Review, 95(2): 163-207.

Over, D. (2004). Rationality and the Normative/Descriptive Distinction. In Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and

Decision Making, D. J. Koehler and N. Harvey (eds.), Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 3-18.

Scanlon, T., M. (1998). What We Owe to Each Other, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Simon, H. A. (1983) Reason in Human Affairs. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Skorupski, J. (2010). The Domain of Reasons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, M.(2009). Desires, Values, Reasons, and the Dualism of Practical Reason. Ratio 22(1): 98-125.

Smith, M. (2012). Naturalism, absolutism, relativism. In Ethical Naturalism: Current Debates, S. Nuccetelli and G.

Seay (eds.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 226-244.

Sterelny, K. (2012). From fitness to utility. In Evolution and Rationality, S. Okasha & K. Binmore (eds.) Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 246-273.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Street, S. (2006). A Darwinian Dilemma for Realist Theories of Value. Philosophical Studies 127, no. 1: 109-166.

•

Street, S. (2008). Constructivism about practical reasons. In Oxford Studies in Metaethics 3, R. Shafer-Landau

(ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 207-246.

Williams, B. (1981). Internal and External Reasons. In his Moral Luck, 101-112.

•

Objection

• naturalistic conception of rationality does not really

address the questions that are of great importance

to us, questions that are connected to our intuitive

conception of reasons, i.e. what we intuitively think

we have reasons to do (cf. Smith 2012, 244-245).

• the case of professional criminal

what would be the purpose of our blaming and

holding responsible some person that rationally

does not care about what morality demands?

would not this position just make any set of

consistent preferences equally valuable and not

amenable to rational criticism?

1. Answer

• we can make a difference between kinds of

reasons

– moral, epistemic, aesthetic, rational reasons, etc.

• so, one can have a moral reason to do

something and be morally responsible for

acting in that way

• however, failing to comply with the moral

demand will not imply rational failure

2. Answer

• the purpose of our activity of blaming and holding

responsible will depend on what we want or what

goals we actually find valuable

• if we want to reap the benefits of living in an ordered

society we have to endorse some moral rules to

regulate our interactions

- from this perspective practice of blaming and holding

responsible has a definite purpose

• However, as naturalists we cannot claim that every

rational agent has an a priori reason to care about or to

be committed to a full cooperation in some community

and to obey its norms

Possible replies

• MA SR

• MN ~(SR)

Railton (1986)

Smith (2012)

Ambiguity

• how to interpret ‘moral demands apply to

everyone’

• every actual human being

• every possible human being

• every possible rational being M. Smith

Objection

• Why should we rely on current scientific

practice?

• That is what it means to be a methodological

naturalist – current practice has a default

authority

Objection

• The argument that relies on methodological

naturalism is circular

• For example, the concept of instrumental

rationality comes from a particular philosophical

theory of rationality to argue that science

gives it some legitimation constitutes a sort of

confirmation bias

• Hence the authority of science cannot settle the

philosophical question which principles of

rationality are valid

Answer

• Instrumental concept of rationality has explanatory

and predictive value

• cognitive science – explaining and predicting behavior

and cognitive processes

• economy – explaining and predicting the behavior of

the market

• social sciences – explaining the evolution of

cooperation and social dynamics

• so, confirmation comes from the successes of the

paradigms that use the concept of rationality

• Plus – naturalism does not give support to the claim

that there are intrinsic values or purposes in the nature

Psychopathy Check list-revised

Factor1

Interpersonal

1. Glibness/Superficial charm

2. Grandiose sense of self-worth

4. Pathological lying

5. Conning/Manipulative

--------------------------------------Affective

6. Lack of remorse or guilt

7. Shallow affect

8. Callous/Lack of empathy

16. Failure to accept

responsibility

Factor2

Lifestyle

3. Need for stimulation

9. Parasitic lifestyle

13. Lack of realistic, long-term goals

14. Impulsivity

15. Irresponsibility

-----------------------------------------------Antisocial

10. Poor behavioral controls

12. Early behavioral problems

18. Juvenile delinquency

19. Revocation of conditional

release

20. Criminal versatility