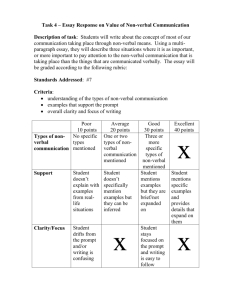

The contribution of population studies to

advertisement

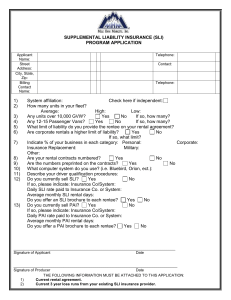

The contribution of population studies to understanding SLCN: The whole is greater than the sum of its parts Sheena Reilly 11th May 2015 – Born Talking Seminar - Norwich Outline • Setting the scene about population studies • Population vs clinical studies: it’s not a competition • What is the value of population studies? • What have we learned? • Trajectories • Predictors • Associations • The SLI story • Data from series of longitudinal, population studies • Why are we frustrated by some of the findings? 2 Bridget Taylor – Seminar 1 Jan 2015 3 • Birth cohorts • Community cohorts • Clinical cohorts or case series 4 5 A population view of language Population: 5.8 million; 1.2 million children 6 A population view of language 7 Community – Language focused studies Early language in Victoria Study ELVS • 6 metropolitan local government areas (LGAs) • ABS - Socioeconomic Indexes for Areas used to select LGAs • Maroondah & Whitehorse (high SES) • Banyule & Brimbank (middle SES) • Whittlesea & Casey (low SES) 8 Longitudinal Clinical or Case series • Manchester Language Study – Conti-Ramsden • • The largest UK study of individuals with a history of SLI. • A random sample of all 7 year old children who were attending language units in England in 1995. Late Talkers Cohort – Rescorla • 53 mother–child dyads from middle class or upper middle class white families. 9 Population view of low language Populations Clinic presenters 10 11 Receptive and expressive language & non-verbal performance at 4 and 7 years of age. Help seeking behaviour shown in the 12 months prior 4 years of age 100 81 50 50 81 100 Expressive Language 150 150 4 years of age 50 85 100 Non-verbal IQ Help sought 150 50 No help sought 85 Help sought 7 years of age No help sought 100 50 81 Receptive Language 100 81 50 150 7 years of age 150 150 100 Non-verbal IQ 50 85 100 Non-verbal IQ Help sought 150 50 85 100 Non-verbal IQ 150 No help sought Help sought No help sought 12 Receptive and expressive language at 4 and 7 years of age: help seeking behaviour in the 12 months prior Receptive Expressive 13 Summary of similarities/differences Population/community All children or representative sample of children with condition Clinical Sub-group of children with condition May be referred or self selected because of particular traits e.g. higher parent concern Full range of ability(s) Likely to be more severe or have co-morbidities Prospective information available Retrospective re early development Typically Longitudinal Cross sectional or Longitudinal Inbuilt comparison group Control group* (recruited if available) Can extrapolate findings to population Findings only relevant to clinical cohort *information about early development of control group often retrospective 14 Bridget Taylor – Seminar 1 Jan 2015 15 Understanding SLCN • Focus on complex interactions within and between environmental and biological systems • Holistic, not reductionist • Ability to concurrently study speech, language and fluency noun! receptive! grammar pragmatics expressive verb! Acknowledgments: Jeff Craig 16 Access to populations has permitted study of language and its interconnectedness to: • Other aspects of communication • Literacy • Education • Psychosocial development • Samples that will be large enough to permit analysis of gene-environment interactions 17 Population health gains 18 Outline • • Setting the scene about population studies • Population vs clinical studies: it’s not a competition • What is the value of population studies? What have we learned? • Trajectories • Associations • The SLI story • • Data from series of longitudinal, population studies Why are we frustrated by some of the findings? 19 Knowledge From Our Longitudinal Studies • Typical and disrupted phenotypes (trajectories) of language development • Environmental and biological factors predicting variation • Social, psychological and educational development • Health care, education, welfare and societal costs • Potential for intervention and factors influencing efficacy 20 21 Data collection points 8mth 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Q Q Q Q Q Q A A A A Q T A Q T A 8 9 Q 10 11 Q T A C 12 13 14 Q T C child child child child & parent child Q : parent-report questionnaire A : face-to-face assessment (child and/or adult) T: Teacher report C: child self report 22 ELVS is measuring • Language & communication • General development & health • Family history • Socio-demographic details • Mental health & family stress factors • Parent-child interactions • Child behaviour & temperament 23 ELVS Cohort • N = 1910 • 50.5% male, 49.5% female • 3.1% (60) premature (<36 weeks) • 2.8% (53) non-singletons • 6% (127) speak a language other than English in the home (~ 50 different languages spoken) 24 Language: Expressive vocabulary at 2 years n =1742 O 679 234.7 287.7 words 261.3 * MB-CDI: Fenson et al, 1994 (Reilly et al Pediatrics 2007; Reilly et al IJSLP 2009) Mean SD Range Total 261.3 162 0 - 679 Girls 287.7 159.7 0 - 679 Boys 234.7 160.6 0 - 679 Late talkers* at 2 years 19.7% (n = 333) 261.3 679 O < 79 Average words 39 < 119 Average Words 65 * MB-CDI: Fenson et al, 1994 (Reilly et al Pediatrics 2007; Reilly et al IJSLP 2009) words 27 2 years 4 years 4 years Impaired Impaired 5% late talkers 19% 14% typical impaired 14% 20.6 % impaired 6% typical talkers typical 81% 75% 7 years typical 6% impaired 6% typical talkers 79.4% 2 years typical 73.4% 7 years Impaired 4% late talkers 19% typical 15% impaired 6% typical talkers typical 81% 75% 28 Five substantive classes Typical - development in the typical range at each age Precocious (late) - typical development in infancy followed by high probabilities of precocity from 24 mths onwards Impaired (early) – delayed development in infancy followed by typical language development thereafter Impaired (late) -Typical development in infancy but delayed from 24 mths onwards Precocious (early) - high probabilities of precocity in early life followed by typical language by 48 mths Ukoumunne et al 2011 29 Characteristics indicative of social advantage were more commonly found in the classes with improving profiles. Okoumunne et al 2012 Characteristics indicative of social advantage were more commonly found in the classes with improving profiles. 30 And between 4 and 7 years 100 80 60 60 80 100 CELF-4 Expressive Language Score 120 Expressive Language 120 Receptive Language 4 5 6 7 4 Child's age in years High (32.7%) Medium (53.1%) 5 6 7 Child's age in years Low (14.2%) High (27.1%) Medium (57.9%) Mean score and 95% confidence interval presented, groups derived by Latent Class Analysis Low (15.0%) Language at 4 and change from 4 to 7 CELF core age 4 (z score) Change from 4-7 (z score) Mean diff -0.04 95% CI p 95% CI (-0.13, 0.04) 0.31 Mean diff -0.03 0.19 (0.13, 0.25) 0.00 0.11 (0.04, 0.18) 0.00 16-18 vs. post school -0.06 (-0.25, 0.12) 0.51 -0.16 (-0.38, 0.05) 0.13 Less than 16 0.14 (-0.05, 0.34) 0.14 -0.07 (-0.30, 0.16) 0.54 Young Mum2 -0.24 (-0.46, -0.01) 0.04 0.10 (-0.17, 0.37) 0.46 Disadvantage (1 sd) Family language ability (1 sd) Maternal Education p (-0.13, 0.07) 0.61 Non English Speaking -0.84 (-1.09, -0.58) 0.00 0.61 (0.31, 0.91) 0.00 Background 1adjusted for child’s gender, IQ, autism, developmental delay, and birth order 2up to age 24 at child’s birth 32 Individual language & literacy trajectories for 20 children selected at random Taylor et al 2014 33 Language and literacy patterns 2,792 CHILDREN 4 years 2474 start middle-high 318 start low 198 188 120 6 years 2286 308 low 2484 196 220 112 8 years 2264 332 low 2460 222 110 10 years 381 finish low 271 2189 2411 finish middle-high 34 34 5 most common language and literacy patterns from 16 possible patterns for 2792 children Age 4 Age 6 Age 8 Age 10 Language Language Language Literacy Middle-High Middle-High Middle-High Middle-High n % 1915 69 202 7 Middle-High Middle-High Middle-High 118 4 Middle-High Middle-High Middle-High Low Low Low Low Low Middle-High 27 1 Low Low Low Low 26 1 • Start on-track and stay on-track is the most common pattern • Start behind and stay behind is the least common pattern 35 Acknowledgements • Language & Learning Group, Division of Mental Health, Norwegian Institute of Public Health • Synnve Schjolberg, Group Leader • Imac Zambrana • Eivind Ystrom • Norwegian Research Council • Norwegian Ministry for Education • Dept Psychology, University of Oslo • Francisco Pons 36 Trajectories of Language Delay from age 3 to 5 Language Delay at 5 years Language Delay at 3 years Yes No Total Yes 318 (3%) 529 (5%) 847 (8%) No 688 (6.5%) 9 052 (85.5%) 9 740 (92%) Total 1 006 (9.5%) 9 581 (90.5%) 10 587 (100%) Language Delay at 5 years Language Delay at 3 years Yes No Total Yes 318 (3%) 529 (5%) 847 (8%) No 688 (6.5%) 9 052 (85.5%) 9 740 (92%) Total 1 006 (9.5%) 9 581 (90.5%) 10 587 (100%) Persistent; Transient; Late-Onset 37 What about the recovered the late talkers? Dale et al (2014) Am J Speech-Language Pathology 2014 Longitudinal study of twins from age 2 years Tracked language development at 4, 7 and 12 years Resolved late talkers: No more at risk of later language imp. than age and gender matched controls Recommend: Periodic monitoring of recovered late talkers & Screening child in low normal range at school entry for signs of late language difficulties 38 Predictors 39 Predicting Outcomes at 2 & 4 years 2 years: 12 putative risk factors/predictors did NOT strongly predict outcomes Variation explained (4.3% & 7.0%) by any 1 risk factor was small. 4 years: Variance explained at 4 years was around 20% Addition of late talking status (2 years) helped explain 23.6% (rec) and 30.4% (exp) language status. Reilly et al Pediatrics 2007 & 2010 40 Persistent Language Difficulties at 5 years 3% (n=318) of overall sample had persistent language difficulties 38% of children with language delay at 3 years had language difficulties at both time points Odds of having a persistent language problem: • Doubled - for boys • Doubled - family history of late talking • Doubled - poor comprehension skills at 18mths • Increased – lower paternal education Eadie et al 2014 41 Transient Language Difficulties at 5 years 5% (n=529) of overall sample had transient language difficulties between 3 and 5 years Odds of having a transient problem: • Increased - family history of • • late talking or speech difficulties • Increased - poor comprehension skills at 18mths • Doubled – lower levels of maternal education • Increased – higher birth order Eadie et al 2014 42 Across international studies 4, 5, & 8 year old findings corroborate that More than half of the late talkers do not present with language difficulties at school entry Trajectories that broadly represent persistent, transient and late onset language impairment exist across languages Poor early comprehension skills are a strong & consistent predictor of persistent problems, particularly for girls Family history of speech, language & literacy difficulties is important & may be a discriminating factor regarding language trajectories Eadie et al 2014 43 Associations The association between child language problems and social, emotional & behavioural difficulties from 4-7 years A population-based longitudinal study Associations In a population-based sample of 4-7 year old children To examine cross-sectional relationship between Low Language and SEB Difficulties @ ages 4, 5 and 7 To describe the pathways of LL and SEB Difficulties over time Measures of key constructs Construct 4yo Language CELF-P2* CELF-4^ SEB Difficulties SDQ# 5yo SDQ 7yo CELF-4 SDQ *Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – Preschool Edition (2nd) ^ Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – 4th Edition – Australian Edition # Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire 47 Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire SDQ Domain Hyperactivity/inattention Conduct problems Peer problems Emotional problems Prosocial behaviour Total Difficulties Score • 25 items • Parent report • 3-point scale - not true, somewhat true, certainly true 48 Movement between groups over time Typical Language & Typical SEB Only Low Language Only SEB Difficulty Low Language & SEB Difficulty 49 4 years of age n (%) 5 years of age % 7 years of age % 610 (79%) 84% 78% 76 (10%) 9% 13% 59 (8%) 5% 6% 26 (3%) 2% 3% Typical Language & Typical SEB Only Low Language Only SEB Difficulty Low Language & SEB Difficulty 50 4 years of age % 5 years of age % 7 years of age % 610 (79) 84 78 9 13 5 6 2 3 45% 10 45% 3% 8% 26 (3) No Low Language & No SEBD Low Language only SEBD only Low Language & SEBD 51 4 years of age % 5 years of age % 7 years of age % 84 78 9 13 5 6 2 3 568 (93) 79 29 (5) 12 (2) 1 (0) 34 (45) 10 34 (45) 2 (3) 6 (8) 38 (64) 1 (2) 8 19 (32) 1 (2) 5 (19) 8 (31) 3 5 (19) 8 (31) Typical Language & Typical SEB Only Low Language Only SEB Difficulty Low Language & SEB Difficulty 52 5 years of age % 4 years of age % 7 years of age % 561 (87) 568 (93) 79 29 (5) 84 12 (2) 50 (8) 6 (1) 1 (0) 21 (29) 34 (45) 10 34 (45) 2 (3) 9 6 (8) 3 (4) 6 (8) 38 (64) 19 (50) 1 (2) 3 (8) 8 19 (32) 1 (2) 8 (31) 42 (58) 5 13 12 (32) 4 (11) 6 2 (13) 5 (19) 3 78 28 (4) 5 (31) 5 (19) 2 8 (31) Typical Language & Typical SEB 3 (19) 3 6 (38) Only Low Language Only SEB Difficulty Low Language & SEB Difficulty 53 Summary • Strong relationship between LL & SEB problems in children aged 4, 5 & 7 years of age • LL children experience more SEB difficulties • Great fluidity & complexity in both language and SEB development over time 54 The SLI story 55 “LANGUAGE IMPAIRMENT” (JOHNSON & RAMSTAD) “HEARING MUTISM”** FUNCTIONAL (COEN) “CONGENITAL WORD DEAFNESS” (MCCALL) “DELAYED SPEECH DEVELOPMENT” (FROSCHELS) (MOYER) FIRST REPORTED BY GALL (WILDE) (BENEDIKT) BROADBENT UCHERMANN LAVRAND WYLLIE 1822 1853 1865 1866 1872 1873 “CONGENITAL APHASIA” (VAISSE) 1874 1880 1886 1891 1893 1894 1897 1898 1911 1917 DEVELOPMENTAL APHASIA (MORLEY, COURT, MILLER & GARSIDE) CLARUS BASTIN LIMITATIONS IN ATTENTION AND MEMORY HYPOTHESIZED TO PLAY AN IMPORTANT ROLE (TREITEL) DEVELOPMENTAL APHASIA (BENTON) “INFANTILE APHASIA” (GESELL & AMATRUDA) “DEVIANT LANGUAGE” (LEONARD) ”DEVELOPMENTAL APHASIA” (INGRAM & REID) “CONGENITAL AUDITORY IMPERCEPTION” (WORSTER-DROUGHT & ALLEN) “CONGENITAL VERBAL AUDITORY AGNOSIA” (KARLIN) SLI (FEY & LEONARD) “DEVELOPMENTAL LANGUAGE IMPAIRMENT” (WOLFUS, MOSCOVITVH & KINSBOURNE) "INFANTILE SPEECH” (MENYUK) 1918 1929 1947 1954 1955 1956 1964 1968 1972 ”DEVELOPMENTAL APHASIA” (E.G.KERR) WALDENBURG “DELAYED LANGUAGE” (P. WEINER) 1974 1975 1980 1981 1983 “DEVELOPMENTAL LANGUAGE DISORDER" (ARAM & NATION) "DELAYED SPEECH” (LOVELL, HOYLE & SIDDALL) "DEVELOPMENTAL APHASIA” (EISENSON) “SPECIFIC LANGUAGE DEFICIT” (STARK AND TALLAL) “SPECIFIC LANGUAGE IMPAIRMENT” (E.G.LEONARD) Introduction of the term ‘specific’ and SLI Reilly et al 2014 56 “LANGUAGE IMPAIRMENT” (JOHNSON & RAMSTAD) “HEARING MUTISM”** FUNCTIONAL (COEN) “CONGENITAL WORD DEAFNESS” (MCCALL) “DELAYED SPEECH DEVELOPMENT” (FROSCHELS) (MOYER) FIRST REPORTED BY GALL (WILDE) (BENEDIKT) BROADBENT UCHERMANN LAVRAND WYLLIE DEVELOPMENTAL APHASIA (MORLEY, COURT, MILLER & GARSIDE) “DELAYED LANGUAGE” (P. WEINER) DEVELOPMENTAL APHASIA (BENTON) “INFANTILE APHASIA” (GESELL & AMATRUDA) “DEVIANT LANGUAGE” (LEONARD) “CONGENITAL APHASIA” (VAISSE) ”DEVELOPMENTAL APHASIA” (E.G.KERR) WALDENBURG CLARUS BASTIN LIMITATIONS IN ATTENTION AND MEMORY HYPOTHESIZED TO PLAY AN IMPORTANT ROLE (TREITEL) “DEVELOPMENTAL LANGUAGE IMPAIRMENT” (WOLFUS, MOSCOVITVH & KINSBOURNE) "INFANTILE SPEECH” (MENYUK) 1822 1853 1865 1866 1872 1873 1874 1880 1886 1891 1893 1894 1897 1898 1911 1917 1918 1929 1947 1954 1955 1956 1964 1968 1972 “CONGENITAL VERBAL AUDITORY AGNOSIA” (KARLIN) 1974 1975 1980 1981 1983 “DEVELOPMENTAL LANGUAGE DISORDER" (ARAM & NATION) ”DEVELOPMENTAL APHASIA” (INGRAM & REID) “CONGENITAL AUDITORY IMPERCEPTION” (WORSTER-DROUGHT & ALLEN) SLI (FEY & LEONARD) "DELAYED SPEECH” (LOVELL, HOYLE & SIDDALL) "DEVELOPMENTAL APHASIA” (EISENSON) “SPECIFIC LANGUAGE DEFICIT” (STARK AND TALLAL) “SPECIFIC LANGUAGE IMPAIRMENT” (E.G.LEONARD) Descriptions of clinical cases or series of cases Case control studies Observation has driven theoretical approaches Epidemiology Medicine, Paediatrics, Speech Pathology, Linguistics, Developmental Psychology Reilly et al 2014 57 Tomblin and Nippold 2014 Typical Language SLI SLI NSLI Non-Specific LI 58 50 Expressive Language 81 100 150 Expres sive lanSLI gua(expressive) ge versus non-verbal IQ Low Language versus 50 86 20.6% 100 with Low non-v erbal Language IQ SpecificLanguageImpairment Typical development •DTypical • Typical language Typical eveloplanguage mental De+laLow y NV typ ical langu+ag e- lowNV non-verbal score • Low Language + Low NV • Low Language + Typical NV 59 150 150 1 00 81 50 50 81 100 R ecept ive Lang uage 150 Receptive language versus non-verbal IQ at 4 years 100 Non-verbal IQ 50 100 Non-verbal IQ 15 Specific language lmpairment Developmental delayed Normal development Good language - poor non-verbal IQ 50 81 100 Expressive Language Normal development Good language - poor non-verbal IQ 85 Expressive language versus non-verbal IQ 150 150 Expressive language versus non-verbal IQ at 4 years Specific language impairment Developmental delayed 50 150 100 85 81 50 50 Receptive Language Expressive Language Receptive and Expressive Language standard scoresReceptive and non-verbal performance language versus non-verbal IQ 4 years 7 years 85 100 Non-verbal IQ Specific language impairment Normal development 150 50 85 100 Non-verbal IQ Specific language lmpairment Normal development 150 ^ Language & NV IQ within Good normal range; ☐ LowIQNV IQ & Language range; Developmental delayed language - poor non-verbal Developmentalwithin delayed normal Good language - poor non-verbal IQ X – SLI; - Low Language and NV IQ 60 • Two cohorts - Two countries • Different language measures • Iowa - children with SLI and NSLI continuously distributed across range of scores • The two categories derived from recognised cutpoints are somewhat arbitrary. • Children with SLI only differed in language severity scores - significantly higher mean language scores than children with NSL 61 Marked social gradient for language outcomes: Three large scale population studies: - Millenium Cohort Study (MCS) British Abilities Scale - Naming Vocabulary at 5 years by Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile - Growing up in Scotland (GUS) British Abilities Scale – Naming Vocabulary at 5 years by Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile - Early Language in Victoria Study (ELVS) Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF-P2) Core Language at Five years by SEIFA Quintiles Law et al 2013; Reilly et al 2013; Reilly et al 2014 62 MCS GUS ELVS 63 Are outcomes different depending on classification Findings from three longitudinal population studies: - Dollaghan (2004): 3 -4 year olds - Tomblin et al 2013: 10 and 16 year olds - Law et al 2009: 34 year olds 64 Dollaghan (2004) 620 participants drawn from a larger study (n=6000) of otitis media in a socio-demographically diverse population in Pittsburgh, USA. At 3-4 years Language scores were evenly distributed - No evidence of an SLI taxon. - Children with SLI were not a qualitatively distinct group 65 Tomblin et al – Iowa study Psychosocial outcomes* for 6 year olds (SLI and NSLI) at 10 and 16 years of age SLI & NSLI significantly greater levels of behaviour problems than typical controls SLI & NSLI - similar patterns in psychosocial outcomes at both ages. 16 years: children with poor language - less socially skilled regardless of performance IQ. Conclusion: poor language skills at school entry confers elevated risk for psychosocial problems both in the middle and end of the school years. Risk NOT altered by the child’s performance IQ. *Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) Teacher Report Form 66 Law et al 2009 Having SLI and N-SLI at 5 years was associated with: Adult literacy difficulties: N-SLI group (OR: 4.35); SLI group (OR 1.59) Adult mental health difficulties: Low employment: SLI group (OR 2.24) than for the N-SLI group (OR1.88). Long term risk of early language difficulties is important In each case significant predictors of adult outcomes were social factors 67 Outline • Setting the scene about population studies • Population vs clinical studies: it’s not a competition • What is the value of population studies? • What have we learned? • Trajectories • Predictors • Associations • The SLI story • Data from series of longitudinal, population studies • Summary • Why are we frustrated by some of the findings? 68 Summary • Trajectories 69 Preschool (3 years) 70 Kindergarten (4 years) 71 Primary school (5 years) 72 Primary school (6 years) 73 Primary school (7 years) 74 Set priorities for research into Language Impairment Development of practical tools: Risk prediction tools that will zero in on children destined for lasting Language Impairment 75 • Not linear • The way language develops is complex and can accelerate, plateau and sometimes go backwards. • These fluctuating developmental pathways make it hard to accurately predict persistent Language Impairment • A strong biological trajectory dominant in the early years; social disadvantage helps explain more variance in outcome by 4 years. • Gap may widen by 4 years - possibly because of cumulative exposure to less rich language environments 76 Summary • Contrasting with fluidity to age 4, language ability across the child population is better delineated from ages 4 to 7 • But there is potential for change in the individual child • Family language environment was the most salient social risk factor 77 Clinical and Public Health implications • Activation and acceleration rates vary • Surveillance rather than screening approach may be required • Language development - vulnerable to further disruption by social disadvantage in the later preschool years. • While sobering, offers a fairly prolonged window of early childhood during which these impacts could be genuinely prevented, rather than simply ameliorated. 78 Summary • Predictors 79 Predictors • • Unlikely to be helpful in screening for language delay in the earlier years (< 2 years) More helpful in identifying children with Low Language by 4 years Recommendation • Language promotion activities in infants younger than 24 months – targeted and based on the level of communication skills displayed 80 Summary • Associations 81 Summary • Strong relationship between LL & SEB problems in children aged 4, 5 & 7 years of age • LL children experience more SEB difficulties • Great fluidity & complexity in both language and SEB development over time 82 Summary • SLI 83 • Remove ‘specific’ and use the term Language Impairment (LI) • Abandon the exclusionary criteria* • Whilst they are convenient for experimental research they do not reflect the real world where symptoms and conditions may overlap and co-morbidity may emerge over time. • Agree definition and criteria for research and test these in existing population studies to inform clinical services and policy * All of them? 84 Outline • Setting the scene about population studies • Population vs clinical studies: it’s not a competition • What is the value of population studies? • What have we learned? • Trajectories • Predictors • Associations • The SLI story • Data from series of longitudinal, population studies • Summary • Why are we frustrated by some of the findings? 85 New knowledge • Access to populations has revealed levels of complexity not recognisable in case-control designs. • More complex than persistent vs resolution • Appreciation of continuities and fluctuations with fluidity -continuing into school years • IQ discrepancy not relevant to long term language outcomes • Exclusion criteria create convenient ‘research’ groups • • Maybe important for imaging studies Social gradient strong – language hyper sensitive to disadvantage 86 Fitting policies and services to language patterns • The job of fitting policies and services to language patterns is easier if language patterns are stable and predictable • The job of fitting policies and services to language patterns is NOT easy when language patterns are unstable and unpredictable • Based on the patterns we see, we have to ask the question, “How well do policies and services fit these language patterns? Acknowledgement to Cate Taylor CRE conference 2014 87 Fitting population patterns to clinical context • Speech pathologists • The patterns you observe in children in specialist service systems may not fit the patterns we see in the general population • Your job is to change growth trajectories • Unstable growth patterns provide more scope for change than stable growth patterns (e.g., height) Acknowledgement to Cate Taylor CRE conference 2014 It’s called curiosity 88 Shifting to personalised and population medicine • “….. clinicians have a responsibility to the population they serve, to the patients they never see, as well as to the patients who have consulted/been referred. • “….. clinicians, while still focused on the needs of the individual …… when in the consultation, also make decisions about the allocation and use of resources to maximise value for all the people….they serve • “This is different from management of a service for the patients who present to the service”. Gray, A. (2013). The art of medicine: The shift to personalised and population medicine. The Lancet, 382, 200-2001. 89 ‘The new responsibilities for the clinician practicing population “speech pathology”* not only includes maximising value by getting the right outcomes for the right patients in the right place with the least use of resources, but also ensuring the prevention of inequity related to age or gender or race or social class’. ‘Population “speech pathology”* is not a new specialty, it is a new paradigm that I believe every clinician will sooner or later adopt, with a proportion of clinicians being allocated explicit time for working for the whole population’. * Inserted 90 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT & DISORDER: “There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don't know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don't know we don't know.” 91 Population health gains 92 Acknowledgements • Centre for Research Excellence in Child Language - Gold, Goldfeld, Law, McKean, Mensah, Morgan, Tomblin, Wake, • Early Language In Victoria Study - Bavin, Bretherton, Carlin, Eadie, Gold, Prior, Mensah, Okoumunne, Wake. • Hearing Language and Literacy group - Cini, Conway, Pezic • Cate Taylor 93 Thankyou Research Snapshots: late talking www.mcri.edu.au/CREchildlanguage 95 96 97 Population health gains 98 Morbidities of language delay Social, emotional & behavioural difficulties with language impairment @ 7 years a N=189; b N=881 SDQ subscale Language impairmenta M (SD) No language impairmentb M (SD) p value Effect size Emotional problems Conduct problems 2.0 (2.1) 1.6 (1.7) 0.006 0.2 1.8 (1.7) 1.3 (1.5) <0.001 0.3 Hyperactivityinattention 4.1 (2.7) 2.8 (2.3) <0.001 0.5 Peer problems 1.2 (1.7) 0.9 (1.3) 0.005 0.2 Prosocial behaviour Total difficulties 8.1 (1.9) 8.4 (1.6) 0.05 -0.2 9.0 (4.7) 6.6 (4.7) <0.001 0.5 99