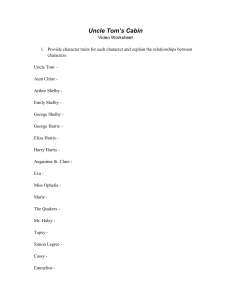

Uncle Tom's Cabin - Marian High School

advertisement