Studies in Liminality

advertisement

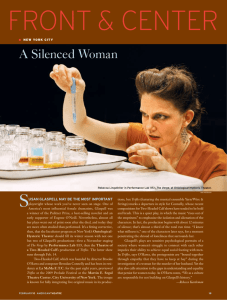

Studies in Liminality: A Review of Critical Commentary on Glaspell's Trifles Lisa Crocker Dramatist Susan Glaspell wrote at a time when the boundaries between the private and public spheres were beginning to break down. No longer relegated to the home, but not yet accepted in the marketplace, women were caught in a position of liminality, pinned between the traditional female and male worlds by the expectations of both. Glaspell's play Trifles falls among the many shades of gray in this interface of perceptions, not only because of its context and content, but also because of the critical reaction to the play. Although most criticism discerns gender conflict in the indeterminate area between law and justice in Trifles, both the conflict and its consequences change form as each critic sees a different shape in the shadows. Some critics find that gender differences create a dichotomy of perception in Glaspell's examination of law and justice. In "Trifles: The Path to Sisterhood," Phyllis Mael argues that the evolution of the women's relationships, from tenuous connection to collusion, illustrates the female ethos. Mael feels that the play's "moral dilemma" highlights the innate differences between male adherence to theoretical principles of morality and female empathic ethical sense which considers "moral problems as problems of responsibility in relationship" (282-83). Although the women draw closer as the men, using "abstract rules and rights," make comments that "trivialize the domestic sphere," ethical solidarity comes only after Mrs. Peters moves from "acquiescence to patriarchal law" to empathy, thus effecting a change "from a typically male to a more typically female mode of judgment" (283-84). This switch allows them to formulate a "redefinition of . . . crime" which finds more culpability in their earlier failure to help Minnie than in their "moral choice" to suppress evidence (284). Karen Alkalay-Gut, in "Jury of Her Peers: The Importance of Trifles," also finds the gulf between male and female perceptions of judgment to be central to the play. Alkalay-Gut believes that the unfolding evidence not only unites the women, but highlights the division between "woman's concept of justice," which entails "social" and "individual influences, together with the details that shaped the specific act," and "[t]he prevailing law [which] is general, and therefore . . . inapplicable to the specific case" (8-9). As the "distance between the laws of the kitchen and the outside world increases," the women realize that the breach "negates the possibility of a 'fair trial' for Minnie Foster" (3, 8-9). Satisfied that Minnie's husband behaved so heinously that the "murder was totally understandable," they dispense justice by circumventing the law (6). According to Alkalay-Gut, the women are "clearly secure" about the correctness of their actions; their "secretive manner is one of superiority" (9). An entirely different path is taken by Linda Ben-Zvi, who, in "'Murder, She Wrote': The Genesis of Susan Glaspell's Trifles," asserts that Trifles is less a comment on innate gender disparities than on assigned gender roles. Suggesting that "their common erasure" provides the impetus for women's actions, not "women's natures," she believes the question of guilt or innocence is irrelevant; what is on trial in the play is female "disenfranchisement" (158, 157). By focusing on the cruelties of Minnie's existence, her isolation, her "lack of options," and "the complete disregard of [her] plight by the courts and by society," Ben-Zvi feels that Glaspell "concretizes" the position of women in her society, moving the discussion beyond abstract problems of perception (157). The playwright's tactics force a recognition of "the central issues of female powerlessness . . . and the need for laws to address such issues" (157). The women's arrogation of authority serves as "an empowerment," as Ben-Zvi notes: "Not waiting to be given the vote or the right to serve on juries, Glaspell's women have taken the right for themselves" (158). Thus, the female enactment of judicial power subverts traditional concepts of law and justice. Subversion is also the theme of Marsha Noe's "Reconfiguring the Subject/Recuperating Realism: Susan Glaspell's Unseen Woman" which makes the ultimate statement on the indeterminate status of women in Glaspell's world by focusing on Minnie's absence. According to Noe, the dramatic device of a protagonist who is present only by insinuation "centers attention on woman and the ways in which the patriarchy marginalizes her . . . " (38). The absent woman makes a mockery of male authority; not only does she "elude the male gaze," and, consequently, his control, but she calls into question the androcentric judicial system (38). Noe points out the need to trace the chain of cause-and-effect behind Minnie's action before assigning guilt: "Alienated from her husband, powerless and silenced by . . . her marriage . . . Minnie is an unseen woman long before she murders John Wright" (46). Unseen both "literally" and "metaphorically," Minnie becomes a surrogate for all the invisible women in Glaspell's society (46). Contrasting Noe's external focus, Veronica Makowsky, in Susan Glaspell's Century of American Women: A Critical Interpretation of Her Work, sees the conflicts between law and justice in Trifles as a reflection of Glaspell's internal discord. Makowsky writes that tensions between the playwright's love for her husband, George Cook, and her resentment over his unfaithfulness found release in the "rebellions" of her characters, whose "actions demand that the patriarchal world consider their feelings and situations as something more than domestic 'trifles"' (61). However, while Glaspell recognizes the gender dichotomy and demonstrates an empathy with it in her work, Makowsky believes that an ambivalence in her life leads her to treat the mutinies as futile, if not negative, actions. While the "passive rebellion" of Mrs. Hale and Mrs. Peters escapes discipline, Minnie's "active insurrection," the murder of her husband, earns her private and public chastisement (63). According to Makowsky, Minnie's actions afterward "indicate the ineffectual nature of her act"; her voluntary removal "from the center of the kitchen" to the fringes of the room seems to be selfpunishment, an awareness of "her marginalized and outlaw status"; she realizes that "men still have overwhelming power" (63-64). Minnie, who ends "imprisoned and possibly mad," reflects Glaspell's uneasiness "with women who seek autonomy," women she "ultimately condemns . . . as selfish" (146). Law triumphs over justice in Makowsky's dark vision of Glaspell's work. Although the ambiguity of Trifles creates such differing critical perceptions, some common images emerge. Most critical readings focus on female bonding as a means of gaining power; however, as Karen Alkalay-Gut notes, "Underlying this attitude is the assumption that . . . women's lives are individually trivial, and their only strength and/or success can come from banding together" (1). Such a premise defines women through masculine precepts and confirms the male value system, authenticating the power of the public sphere by the perceived need to replicate it. But, as evidenced in the ironicallynamed Trifles, where male disparagement proved male undoing as the women used their assigned invisibility to subvert the law and effect justice, women have a different kind of power. Women's power, subtle and indirect, is one of the liminal elements in Trifles; originating in, but unconfined to, the private sphere, it radiates outward into the indeterminate area, influencing both worlds. Bonding is both a manifestation of women's strength and its source; perhaps Glaspell wished to show the women of her time that they had more power than they--or anyone else--realized. http://itech.fgcu.edu/faculty/wohlpart/alra/glaspell.htm#Criticism