final exam review sheet

advertisement

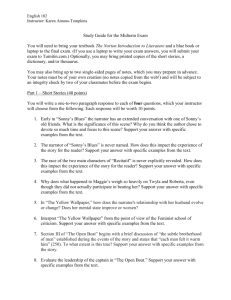

LTEN 26—Dr. Shelley Streeby; TA Lisa Thomas Spring 2011 Final Exam Quick-Reference Study Guide DISCLAIMER: As the TA is not writing the exam, this is merely a reference and does not reflect all of the possibilities for the final exam. Refer to your notes and texts, using this as a supplement. Overarching Themes and Genres: Sensational fiction, sentimentality, political treatises, speeches, poetry, letters, science fiction, naturalism, autobiography (including immigrant autobiography), immigrant fiction Race, ethnicity, nationality, belonging Lynching, spectacle, bodies Political activism and protest (anti-lynching, desegregation, anarchy, anti-conscription, Cold War anxieties, imperialism, environmentalism, immigration, labor, racism) Gendered language and themes (sentiment, claiming masculinity, men’s work and networks, the nation as woman, consumption of women’s bodies, agency and mobility) Cross-generational and familial relations Class tensions and various forms of labor Militancy (as protest and reclamation, for empire-building, for control, for claiming masculinity) Prisons (literal and figurative) Spaces and places (movement, domesticity, belonging, regionalism, law and culture as tied to places such as CA, TX, and NY, history and continuity tied to space/place) Language and bilingualism/multilingualism; perspective and knowledge Engagements with religion and faith -----------------------------------------------Up from Slavery (Washington)—Norton 454-62 highlights/recaps Atlanta Exposition Address at the beginning, highlighting the phrase, “Cast down your bucket where you are” (see esp. 455). focusing on unity and a conciliatory attitude toward the South, recalling the loyalty of slaves to tie whites and blacks together suggests that we must protect ourselves against foreign labor (see esp. 455-56) arguing about being separate elements of the same hand (a controversial notion): “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress” (456). Linked to separate but equal language (Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896) emphasizes the importance of the vote (though we must protect it from unfit voters; see 461-62). emphasizes vocational training (Tuskegee Institute), gradualism, and self-help gets a positive response from Pres. Cleveland that unfortunately focuses on the roles of blacks rather than also whites (excerpts Cleveland letter on page 458). Becomes an awards judge in Atlanta (460-61) but generally won’t have his services bought as a lecturer or writer (458) acknowledges that not all in the African American community accept his views (including the ministry; see p. 460) though sees self as an ambassador for his race Contending Forces (Hopkins)—Norton 495-506 Anson Pollock (villain); Hank Davis and Bill Sampson (other villains, vengeful plantation overseers) Charles and Grace Montfort; Jesse and Charles Montfort (sons) Mr. Whitfield (father) and Elizabeth/Lizzie Whitfield (marries Jesse) Dr. Arthur Lewis (Washington figure) and Luke Sawyer (Du Bois figure) Monsieur Beaubean (Mabelle’s father) and his half-brother (kidnaps and rapes Mabelle when she’s 14) Mabelle/Sappho Clark o Sensational fiction set in antebellum North Carolina and postbellum Boston; Post-Reconstruction critiques o Rumors: Grace’s race, Charles’s plans to free his slaves, charges that he’ll aid them in an insurrection o Pollock’s revenge b/c Grace spurns his advances; lynch-mob imagery as the “committee on public safety” invokes their own law (499), destruction of the home, and claiming the bodies of Grace and her sons as slave property o Luke Sawyer’s speech to the American Colored League invoking militant and Revolutionary War imagery (including Boston Tea Party), sounding like Du Bois: “Under such conditions as I have described, contentment, amity—call it by what name you will—is impossible; justice alone remains to us” (506). o Creating black popular literature, using dime novels and story papers but with a message though sensational The Souls of Black Folk (Du Bois)—Norton 553-68 Opens chapters with epigraphs that are excerpts from poems, plays, black spirituals, and slave songs double-consciousness that he also calls “twoness,” the image of the veil (separation along the “color line”). See page 554 for quotes re: these key concepts. responds to the notion of being perceived as a “problem” and as different because of his race (the “Negro Problem”); rejected despite extensive education and can’t pretend or suffer in silence like other black boys promotes all kinds of education and the training of teachers (see 556, 561, 564-65); diverse forms of art/culture important more militant perspective (of a later generation, though there were others more militant than him—especially after he made concessions during WWI); notes feelings of revenge and different approaches (Nat Turner’s revenge, abolitionist movement—562-63); refuses to flatter the South (see esp. 566-67) explicitly attacks Washington’s conciliatory attitude even as he recognizes Washington’s dilemmas and contributions; challenges the untouchable quality of Washington re: his power (561) also notes the importance of the vote and uses Revolutionary War/Founding Fathers/Dec. of Indep. rhetoric (see 558); typically focuses on black and white identities but brings in Native Americans briefly on 558; merging the individual with the collective; see the last paragraph (568) for key quotes notes that emancipation didn’t end servitude or preserve the African American home (see 557); critiques Reconstruction and makes comparisons to the children of Israel asserting manhood through masculinized rhetoric in his text, refusal to be emasculated making demands through a list structure in his text (see 564-65) “The Comet” (Du Bois)—Elec. Res. Jim Davis and Julia as supposed last survivors after comet spreads “[d]eadly gases” (7)—sci-fi story, disaster, cognitive estrangement in this setting Urban setting full of death and silence; disrupted social norms as Jim can move freely, eat where he wants o “‘Yesterday, they would not have served me,’ he whispered, as he forced the food down.” Detours “to avoid the dead congestion” (8). See page 9 re: Jim and white woman driving, she noticing he’s black—race and class distinctions collapsed b/c of disaster, though she has some paranoia and division in the city (Harlem vs. her neighborhood) are still evident. Sexual tension: “they looked into each other’s eyes—he, ashen, and she, crimson, with unspoken thought. To both, the vision of a mighty beauty—of vast, unspoken things, swelled in their souls; but they put it away” (13). Re-racialized at the end as father and Fred arrive; only New York was affected; assumptions re: Jim’s impropriety, threats of violence against him; Jim reunited with his wife but all seems re-segregated after the moment when it has seemed that only through a disaster could equality exist (see p. 17). “Jesus Christ in Texas” (Du Bois)—Elec. Res. Context of chain-gang labor and lynching in post-Reconstruction era, esp. in South (set in Waco, TX) Stranger—marked as an outsider; his eyes and blackness are emphasized (though he’s not recognized as black at first); connects with colonel’s daughter, black laborers, and black convict/thief; less familiar to whites including the colonel and minister/rector Black Christ’s body subsumed with black convict’s in final image of the man’s lynching for his thievery and contact with a white farmwoman—image of fire and the “crimson cross” repeated Pages 98-99 and 103-04 emphasized in lecture Poetry by Claude McKay—Norton 969-71 sonnet style of poetry o “The Harlem Dancer” Image of a young black woman dancing, object of the male gaze; veil imagery; objectified but admired; imagery of Africa and Jamaica along with Harlem; notes performative aspect of this in her “falselysmiling face” (line 13). Linked to Du Bois’s double-consciousness. o “Harlem Shadows” Harlem at night, veil imagery; prostitutes walking the streets; walking, weariness, shame; critiquing society more than the women. o “The Lynching” Christ-like imagery; spirit separated from burnt body, crowds watching the spectacle, unfeeling female voyeurs and gleeful children. o “If We Must Die” Masculine, militant rhetoric; denial of the animalization of African Americans; unity against a “common foe” (line 9); sense of nothing to lose MCKAY CONTINUED o o “Africa” Cradle of civilization, feminized Africa, old and new legacies linked; Egypt and the fall of an empire; ancient slavery and suggested continuity across time and space “America” Feminized America full of negativity but also potential (ambivalence); masculine power of the speaker challenging her/U.S.; notion of time changing status/power, looking to future. Written in England. Poetry by Langston Hughes—Norton 1089-95 unconventional style of poetry that weaves in dialogue, italics, musicality, etc. Hybrid forms and use of vernacular. Internationalism of community (traveled widely), diasporic black identity. Wrote more patriotically after treated as a radical by the FBI but still critical of U.S.; 1920s Harlem Renaissance in wake of WWI; New Negro Movement o “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” Imagery of Africa (esp. Egyptian Nile) and the Congo, moving to the Mississippi/Abe Lincoln/New Orleans; soul and blood likened to rivers flowing; repeats “I’ve known rivers” and “My soul has grown deep like the rivers” o “Mother to Son” Like a speech from a mother to her son, metaphor of climbing stairs (progress); hardship, lessons, perseverance, lack of privilege; repeats “Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair” and stacking up hardship and movement through repeated “And” o “I, Too” Sense of banishment from U.S. but resilience as a “darker brother” (line 2); looking to future change (“Tomorrow,” “Then”—lines 8 and 14); metaphor of eating at the same table as whites; staking a claim on USAmerican identity through “I, too, sing America” and “I, too, am America” (lines 1 and 18) o “The Weary Blues” Slow cadence and musical; narrator listens to a man play the Weary Blues on the piano in Harlem (Lenox Avenue); repeated sound of the piano “moan” and use of assonance (rhyming vowels); embedded dialogue of the melancholy song, onomatopoeia of the piano pedals and/or his feet on the floor; ends with sleep and the song resonating o “Mulatto” Italicized declarations as black son speaks, white father and siblings respond in denial, and black son counters again at the end; recognizing miscegenation and defending the bodies of black women (countering repeated questions “What’s a body but a toy?” and “What’s the body of your mother?”); repeats “A little yellow / Bastard boy” along with the color yellow o “Song for a Dark Girl” Repeats “Way Down South in Dixie” to mock a popular minstrel song; image of a lynched body (female? Note title) hanging from “a gnarled and naked tree” (line 12); broken heart; questioning a white Jesus about the use of prayer under these conditions o “Visitors to the Black Belt” White outsiders/visitors distanced from Harlem; narrator informs them about real, lived experience “[o]n this side of the tracks” (line 4) and “[i]n Harlem” (line 8); takes us inside a Harlem home; questions the identity of the outsider and urges him/her to ask who the narrator is (engage with the potential voyeur) o “Note on Commercial Theatre” Accusing an assumedly white “You” of taking and appropriating black music and culture (blues, spirituals), gentrifying and whitening them on Broadway and in the Hollywood Bowl; reclamation of self who wonders if he’ll be talked and sung about; will be himself o “Democracy” On attaining democracy eventually; equal rights as a given; tired of inaction and apathy; sense of immediacy and spurring a greater kind of freedom; ends with “I” addressing “you” (assumed white “you” ignoring the “I” who lives here and also wants freedom) o “Theme for English B” Italicized assignment from the instructor to write a page (writing as actualizing process, self-definition); narrator questions process and identity; descending from the university to Harlem and speaking for Harlem; link to others through common hobbies and emotions; writing as racialized; united with professor though distanced (“That’s American”—line 33); reciprocal education and existence despite racism and resistance Living My Life, vols. 1 and 2 (Goldman)—Elec. Res. Key figures of Emma Goldman (her autobiography); Alexander “Sasha” Berkman, Most, and Fetya; ex Jacob Kershner Immigrant autobiography but not told in usual fashion by beginning with first arrival to states or espousing American Dream; written from memory and through letters (epistolary elements) Sentimental modernism, emphasizing emotions and the body Emphasis on labor/work, community, anarchy (“anarchism = without adjectives”—open and unpredictable, liberation), pleasure and beauty, violence/nonviolence, speech and writing, sexuality (personal and bodily issues as political), rejecting motherhood, WWI and conscription, context of immigrant and espionage acts linked to her trial and deportation See top of p. 7 re: the influence of Haymarket See pp. 11-12 re: Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island (“The last day…,” “Gruff voices…,” “The scenes…”) See p. 16 re: factory work and surveillance (“Now I was in America…”) See p. 30 re: talking to Most early on; New York as an activist center (top of page through “…we may be able to talk”) See p. 36 re: talking to Fedya about her life and binding people together (“We talked about my life…”) See all of p. 41 re: beginning to talk publicly See p. 43 re: relationship with Most and Sasha (“Shevitch and Jonas…” “The meeting was at an end…”) See p. 56 re: the Cause’s stance on dancing and expression (“I became alive…” “I grew furious…”) See pp. 61-62 re: having children and free love (“I had learned…” “I told Sasha…”) See all of p. 494 re: San Diego incidents, continuing through p. 501 See all of p. 503 re: protecting her face, gendered critique See p. 597 re: US criticized (“In the spirit…”) See p. 600 re: free speech for the soldier who protests Goldman (top half of page) See p. 640 re: US during WWI (“America…”) See p. 714 re: bond with Sasha upon exile (“I decided…,” “‘You are staying…’”) See p. 717 re: irony of being deported in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty (“I looked at my watch…”) “Barn Burning” (Faulkner)—Norton 1048 Snopes family (Abner as father, Sartoris/Sarty as son); Major de Spain; less-descript female and black characters (hysterical women, bovine twin sisters, black servants and messengers) Modernism and naturalism, experimenting with point of view and chronology, language of blood and inheritance, determinism and animalistic elements From court removal to a new home (sharecropping) court again with de Spain final barn burning at close Sarty’s struggle re: loyalty to family and blood in the face of Abner’s violence (words and actions “without heat”; father described as a black figure, a silhouette, with a limp from a supposed Civil War wound [horse thief]); Sarty’s inner thoughts often represented through italics though otherwise narration is third-person Abner’s arrival at de Spain’s and the rug scene pp. 1052-53—“Then with the same deliberation he turned; the boy watched him pivot on the good leg and saw the stiff foot drag round the arc of the turning, leaving a final long and fading smear. His father never looked at it, he never once looked down at the rug” [1053]) Relations between black and white laborers; Abner’s resentment despite potential solidarity; character type of “poor white trash”; Abner: “Pretty and white, ain’t it? . . . That’s sweat. Nigger sweat. Maybe it ain’t white enough yet to suit him. Maybe he wants to mix some white sweat with it” (1053). Ends with movement—Sarty running after he warns de Spain and hears the shots, yet still defending Abner “Be American” (Bulosan)—Norton 1122-27 Narrator and his cousin Consorcio who comes to San Francisco from the Philippines ethnic bildungsroman (formation, education, progression, and conflict; foreign estrangementintegrated citizenship but often not full or unblocked) and immigrant literature (challenges bildungsroman’s optimistic view of integration); also picaresque (movement, adventure esp. in underbelly of society, mapping low spaces, often episodic) context of laws barring citizenship and rights, altered in WWII as Filipinos enlist See the introduction of Consorcio from the first paragraph and how “he talked about his Americanization with great confidence” (1122). Consorcio wants to change the law to earn citizenship in less than five years (1123). Acquires books, gets a job, goes to night school—optimism, naïveté. Migratory lifestyle of male workers highlighted pp. 1124-25: anti-domestic, finding home in homeless conditions, male networks, communicating through harvested products. Mapping spaces of migrant labor. Narrator finds Consorcio later, more dejected and with a more tragic tone to offset earlier comic tone, accuses cousin/narrator of being a dreamer (1126-27). Claiming a different kind of citizenship in the end (takes us through WWII) by being a writer and labor organizer; ambivalent patriotism in the end, critique of the American Dream “Yoneko’s Earthquake” (Yamamoto)—Elec. Res. Hosoume family—mother, father, Yoneko, and Seigo; Marpo as 17-year-old Filipino hired man Issei (1st gen.) and Nisei (2nd gen.) relations; context of naturalization laws Yoneko’s Christian fervor highlighted at beginning but dies down after Marpo is dismissed following the earthquake that injures her father and the affair between Marpo and Mrs. Hosoume, and after Seigo’s death; prays to God to stop the aftershocks, but He won’t listen (51) Mother’s Christianity heightened as story ends (guilt re: affair abortion Seigo’s death) See first paragraph re: context in 1933, Christianity, and farm work (which hints at Japanese exclusion re: property rights) The ring and the trip to the hospital (abortion) as signs of infidelity, masked by limited perspective of Yoneko through whose eyes we see the story (though it’s told in third-person) Intergenerational issues, treatment of Japanese-Americans and Filipino-Americans, gender and sexuality, guilt and shame, faith and skepticism, assimilation and law “A Fire in Fontana” (Yamamoto)—Elec. Res. Autobiographically based regarding time spent writing for a black newspaper, responding to family’s death in Fontana, and seeing the Watts riots years later See p. 151 re: the bus ride and the discussion of segregation and feeling partial solidarity with African Americans re: segregation and WWII-era internment, despite access to Whites Only facilities See page 153 re: the introduction of Mr. Short when he asks the newspaper for assistance; Miss Moten’s declaration that she “hate[s] White people!” Anger at self for writing an “impartial story” in “cautious journalese” (154). Feels complicit, doesn’t erase or forget. Autobiographical story foregrounding personal stance versus journalistic objectivity she critiques. See p. 157 re: watching the Watts riots on her TV from the safety of her home, where she arrived “on the coattails of a pale husband.” Sees the looting and fires and thinks of the Short family burning. “Service Call” (Dick)—Elec. Res. Courtland—research director for Pesco Paints in SF Bay Area (owned by Pesbroke); wife Fay; coworkers Hurley, Anderson, MacDowell Nameless repairman from the future, repairing and selling swibbles—part living, part machine; invented by J. R. Wright after war between America and Russia; control Contrapersons, measure loyalty to ensure all have the same ideology Cold-War context and fears re: government control, McCarthyism, technological advances, biotech anxieties See repairman’s language and explanations on p. 32 Sci-fi, use future to comment on present, old technologies existing in supposed future landscape Cognitive estrangement, Novum (new thing) invented to immerse reader in strange world; back and forth between recognition and estrangement in sci-fi “The Mold of Yancy” (Dick)—Elec. Res. Programmer Leon Sipling helping to program John Edward Yancy Taverner sent to Callisto to investigate possible totalitarianism—see discussion of totalitarianism p. 55 and the narrator’s response regarding the use of persuasion on p. 62 (“Torture chambers…”) See officer Dorser commenting on how the two-party government appears to be a model democracy (57) See Yancy’s speech p. 60 re: vigilance (“My friends…”). People called “sheep-like public” (64). Sipling’s decision to program a new Yancy gestalt because he fears this absorption of a message regarding war and controlling trade that the public (including his son) unknowingly mimic Fear of advertising, merging TV/ads and politics, imperialism re: trade “The Minority Report” (Dick)—Elec. Res. John and Lisa Anderton; Ed Witwer as the potential Precrime head replacement; Kaplan as the Army leader Anderton is meant to kill; three precogs predicting future crime (through majority and minority reports—Jerry, Mike, and Donna); Fleming posing as his ally and giving him a new identity as electrician Ernest Temple; colleague Page Anderton’s paranoia re: who’s setting him up, surveillance, ambivalence about women, desire to see his case as an exception and still kill Kaplan in order to save Precrime and maintain checks and balances so Army doesn’t take over; exile in the end See pp. 88-89 re: reminders of war-ravaged landscape (“Behind the wheel…”); Anglo-Chinese War and West Block Alliance resonate with fears about Korean War leading to more conflict between so-called East and West See Kaplan’s motive re: wanting control back on p. 94: “After the Anglo-Chinese War, the Army lost out. It isn’t what it was in the good old AFWA days. They ran the complete show, both military and domestic. And they did their own police work.” Language of disability around the precogs “The Word for World is Forest” (Le Guin)—Elec. Res. Davidson (villain), Lyubov (good guy who befriends and studies Athshean culture); Selver (creechie called Scarface at first; says his wife instructed him to attack Earthling base camp—p. 42) Terrans (Earthings) vs. Athsheans/creechies—colonizing planet for wood; arguments about humanity, slavery, sex slavery/rape, racism, environmentalism Notion that when the colonists came to the planet, “there had been nothing” (35). Being able to sing and dream vs. taking hallucinogens (link to Vietnam War context re: drugs; Le Guin protested the war) Story changes points of view depending on the chapter; several are from Davidson’s POV (most disturbing) Athsheans animalized and dehumanized, ultimately using Terran tools of destruction and killing women; macho rhetoric and the exile of Terran colonists after Davidson’s defeat (imprisonment/isolation); imperialism disrupts equilibrium . . . And the Earth Did Not Devour Him (Rivera)—Novel Begins with the notion of a “lost year” and often focuses on the view of a boy (potential bildungsroman) and the topic of migrant farm work in the central U.S.; a series of vignettes, some of which are a few pages long while others are quiet short and untitled; ends with a fusion of different figures’ voices as the boy reflects while hiding under a house. Key themes: education, religion (women esp. as religious figures), family, labor, language, race, culture, immigration and migration, citizenship and rights, domesticity, gender and sexuality, age, perspective (including narrative and linearity, being looked at as object of the gaze), compressed time (losing time/money) and life expectancy, individual and collective memory Written in 70s but reflecting mostly on 50s (Korean War context apparent); double temporal focus Context of treatment of migrant workers, context of Jim Crow laws in TX and Midwest circuit of labor; bracero program 1940s-1960s re: Mexican contract labor Collective identity through corridos—Mexican-American border ballads In class, the professor focused on: o “The Lost Year” (first and last paragraphs) o “The Children Couldn’t Wait” (esp. re: access to water and losing work time) o “A Prayer” (soldiering as another kind of migrant labor, religion, fuzzy geography re: Utah in Asia) o “Hand in His Pocket” (living with Don Laíto and Doña Bone, bootleggers) o untitled vignette on page 103 re: barbershop refusing to serve the boy o “A Silvery Night” (summoning the devil, afraid to question God’s existence) o “And the Earth Did Not Devour Him” (illness, heatstroke, questioning God’s mercy and existence, repeated “why?”) o “First Communion” (witnessing a sexual liaison, religion and confession, the need to know more) o the untitled vignette from the movie re: the boy removing his button to give to the teacher on p. 119 o “The Little Burnt Victims” (children burning while the boxing gloves are spared, parents leaving children at home to work the fields) o “The Night the Lights Went Out” (gendered ownership, Juanita and Ramón) o “The Night Before Christmas” (mother goes downtown with trepidation to get Christmas gifts for her children and is accused of shoplifting, faints) o “The Portrait” (parents scammed out of a picture of son in uniform) o “When We Arrive” (migrant workers travelling north, constantly looking to their arrival though they “never arrive” [145]) o untitled vignette p. 147 (Bartolo and corridos, reciting his poetry/ballads aloud) o “Under the House” (voices coming together in stream-of-consciousness style, sense of unity at end and not having lost a year after all) Bone (Ng)—Novel Story set around SF Bay Area (esp. Chinatown) that’s told mostly backwards (refusing linear trajectory); 1920s80s/90s Context of Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Page Law of 1875, restrictive covenants re: zoning/residences, Angel Island Sisters Leila (narrator), Ona (commits suicide), and Nina (lives in NY, travel agent to China) Mah and Leon (“He’s not my real father, but he’s the one who’s been there for me. Like he always told me, it’s time that makes a family, not just blood” [1]); Mah’s affair with Tommie Hom Mason Louie (boyfriendhusband; repairs cars and lives in Mission area vs. Chinatown) Chinatown as spatial heterotopia; layered histories; intergenerational relations; paper histories Collision of domestic and work spaces, confounding separate spheres ideology See p. 2 re: Louie’s place at the San Fran Hotel See pp. 6-7 re: Leon’s arrival with “cousin” You Thin Toy and their thoughts about paper BONE CONTINUED See p. 9 re: Leon asking Leila about seeing the Statue of Liberty (“Freedom Goddess”) See p. 20 for embedded poem re: Leila’s thoughts on her mother learning of her marriage to Mason See p. 32 re: Mah’s work sewing at home and Leon’s work at sea (work and domestic space) Generational issues: “We repeat the names of grandfathers and uncles, but they have always been strangers to us. Family exists only because somebody has a story, and knowing the story connects us to a history” (33) See pp. 48-49 re: mother learning to sew after biological father leaves for Australia (work and domestic space) See p. 57 re: Leon’s documents and paper as blood; memory See p. 188 re: Mah telling Leila to test Mason and “have a way out” See p. 191 re: leaving Salmon Alley Generations, family, culture, memory, paper, bones, language, place and space, movement, class and labor, loss and guilt, luck and choice, gender and sexuality, marriage, domesticity Twilight Los Angeles, 1992 (Smith)—Novel Rodney King (black man beaten by LAPD), Reginald Denny (white man beaten by L.A. Four), Latasha Harlins (shooting); continuity with 1965 Watts riots and other police beatings Issues of policing, economic restructuring (“Postmodern bread riot”), and demographic shifts (“multi-ethnic rebellion,” “invisible mid-city riot”) Polyphony (multiple voices); viewing language as quotation and critiquing cybernetic model of vision—encouraging attention to context and grappling with what’s real, Brecht re: acting method of disrupting audience’s ability to forget this is a performance by interrupting it so they must actively interpret See “These Curious People”: Stanley K. Sheinbaum re: gang members vs. police and who’s the enemy (esp. pp. 14-15) See “When I Finally Got My Vision/Nightclothes”: Michael Zinzun re: police brutality and blindness (esp. pp. 19-20) See “They”: Jason Sanford re: who “they” are and treatment by cops as a white man (pp. 21-23) See “Surfer’s Desert”: Mike Davis re: youth , space, and civil rights (pp. 28-31) See “Indelible Substance”: Josie Morales as uncalled witness who wanted to act/stop violence and testify (pp. 66-69) See “A Weird Common Thread in Our Lives”: Reginald Denny re: his beating (esp. pp. 107-08, 110-11) See “Swallowing the Bitterness”: Mrs. Young-Soon Han re: Korean business owners (pp. 244-49; recall video clips) “At Navajo Monument Valley Tribal School” (Alexie)—Norton 1676 Poem; note at top reads it’s based on a photo by Skeet McAuley (a photo of a track and football field right in the midst of desert mountains/plateaus) Link to the history of Tribal Schools and assimilation; imagery links the field and track to images of Native lifeways, bodies linked to the land and to each other, galloping horses—“the eternal football game, / Indians versus Indians” (lines 13-14). “Pawn Shop” (Alexie)—Norton 1676 Prose poem Vanished Indians (“Skins”/redskins); narrator’s absence and absence of Natives in bar—“all the Indians are gone” Collective heart beating under the glass in a pawn shop (where old, pre-owned items gather dust and/or are resold). Sense of recognition of the representative heart. “Crow Testament” (Alexie)—Norton 1677 Poem linking legend of trickster Crow figure with Biblical story of Cain killing Abel—uses Crow as weapon White man as falcon steals salmon from Crow—Crow had no opportunity to flee this country (would need to swim; not enough to be able to fly) Notion that Crow is easy to worship because he’s not ambiguously rendered; notion of self-worship Imagery of war and sacrifice (Crow and firstborn, God and Christ) again linking Native and Biblical stories (even in the poem’s title); Crow riding “a pale horse” Links Crow to reservation alcoholism—redeeming empty beer bottles (redeeming souls at five cents a bottle—redemption as also mercenary) Powerless lamentation and incredulity—after each affront, Crow responds first with, “Damn.” “Do Not Go Gentle” (Alexie)—Norton 1678 First-person narrator and wife grapple w/ Mr. Grief (metaphorical figure) when baby son suffocates in cribcoma Mr. Grief hiding inside people and even the workings of the hospital (“a billionaire” [1678]) Transference of pain onto others, risk of addiction to causing pain to relieve your own “My wife and I didn’t even name our baby. We were Indians and didn’t want to carry around too much hope” (1679). “DO NOT GO GENTLE” CONTINUED Gender—masculine fatherhood (“A father with a sick child is an angry god”) but desire to do something good and buy baby toys, feminized (“I felt like a good woman and I wanted to be a good mother-man”) (1680). Transformative incident in men’s bathroom: men berate a mother’s appearanceheads to toy store but finds it’s a sex-toy shoppurchases vibrator Chocolate Thunder (racialized stereotype and masculine power: “I like to think my indigenous penis is powerful. But it would take a whole war party of Indian men to equal up to one Chocolate Thunder” [1680]) Vibrator as symbol of sex: “It was sex that made our dying babies, and here was a huge old piece of buzzing sex I was trying to cast spells with” (1680). Vibrator as wand—multiplicity of purposes; “humans are too simpleminded” and “think each person, place, or thing is only itself. A vibrator is a vibrator is a vibrator, right? But that’s not true at all. Everything is stuffed to the brim with ideas and love and hope and magic and dreams” (1681). Casting spell in hospital while onlookers are mostly amused; wife sings songs; child (Baby X) revives and is named Abraham. “We deported Mr. Grief back to his awful country” (1681)—foreign. Title is from Welsh poet Dylan Thomas’s 1951 poem (villanelle form) “Do not go gentle into that good night” about his dying father, in which the narrator orders, “Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” “Because My Father Always Said He Was the Only Indian Who Saw Jimi Hendrix Play ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ at Woodstock” (Alexie)—Elec. Res. Narrated by Victor and centering on his relationships with his parents, who divorce; reservation, alcohol, marriage Vietnam War context—war protest and father as hippie, held up as Native American warrior stereotype; father as quasi vanished Indian (claiming to be the only Indian to see Hendrix though likely not [31]) Tension between loving Hendrix’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at Woodstock and not wanting to fight wars for the U.S., a country that’s “been trying to kill Indians since the very beginning” (29) Power behind music and memory (see esp. 34 for memory); survival (32); questioning what reality is (33-34); gender, abandoning one’s family, and assimilation (34) “This is What It Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona” (Alexie)—Elec. Res. Third-person story about Victor, set right after his father’s death; journey of him and old (now abandoned) friend Thomas Builds-the-Fire to retrieve father’s ashes (and savings) from Phoenix Story of travels to and from Phoenix is interrupted by sections on Victor and Thomas’s childhood Reservation life, inability of Tribal Council to pay for all of Victor’s trip; remarks that a day on the reservation starts with waking up, eating, and reading the paper “just like everybody else does”; “It was the beginning of a new day on earth, but the same old shit on the reservation” (73)—like and unlike/other Tension re: celebrating the 4th of July when “[i]t ain’t like it was our independence everybody was fighting for” (63). Space of the airplane as temporarily collapsing distinctions (with Cathy the gymnast) b/c “everybody talks to everybody on airplanes. . . . It’s too bad we can’t always be that way” (67). Father’s isolation in his trailer—stench from his body lingering; taking and dividing his ashes because Thomas has been Victor’s secret protector as a favor to Victor’s father Isolation and death seen in accidentally running over rabbit, “[t]he only thing alive in this whole state” of Nevada (72). Isolation of Thomas, whose father died in WWII “fighting for this country” and whose mother died in childbirth. “I have no brothers or sisters. I have only my stories” (73). Importance of premonitions/dreams and storytelling, not ignoring. Victor only ever wanted “a fair trade” and finds it in agreeing to listen to one of Thomas’s stories (75). “Ghost Dance” (Alexie)—Handout Big cop and rookie (little) cop; FBI Agent Edgar Smith Re-appropriating zombie narrative in Native American historical context; grotesque Setting in Montana of Custer Memorial Battlefield and Little Big Horn River as big and little cop drive Big cop’s dislike for Native Americans in Montana; reservations; arrests 1,217 for crimes related to alcohol abuse Big cop, who holds his crotch while driving (because “[h]e felt safer that way”—later his genitals are eaten by a zombie horse) tells about Crow boys poisoning a girl with Lysol and raping her, arguing that this kind of violence is “a sacred tradition on some of these rez ghettoes” (342). At Custer Memorial Cemetery, big cop repeats his usual speech re: how 256 “good soldiers, good men” died there in June 1876. Blames Natives for killing Custer, whom would have been President and would have improved the country. Sees self as “a man with wisdom,” “powerful intelligence,” he thinks “of the injustice” while the rookie agrees with him (343). Police brutality against hitchhiking Natives; defiancemurder, being disappeared. Blood seeping into earth7th cavalry rises from the earth to consume the big cop Case viewed as a kind of Native protest, digging up bodies and killing the cops in cannibalistic fashion; Smith tries to stay rational. Which is the nightmare? Has premonitions re: various victims’ lives. Fever dreams/vision-fever. Survival. *NOTE: There will be extra credit questions—1) examine the meaning and significance of one poem from Island on its own and in relation to the other poems in the collection and 2) discuss your favorite text from the class and why it’s your favorite.