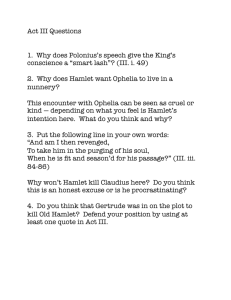

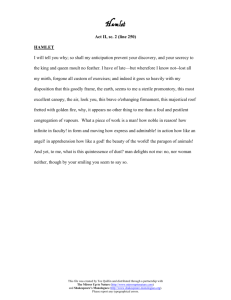

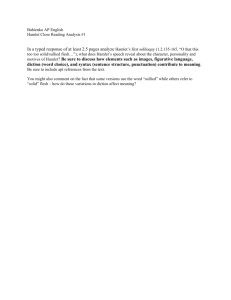

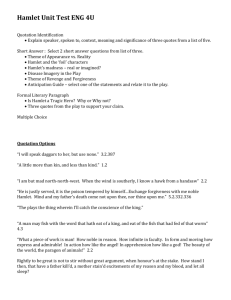

Shakespeare*s *Hamlet* as Drama

advertisement