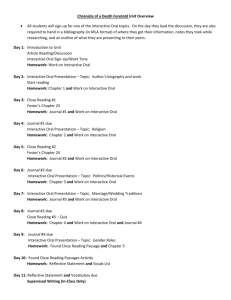

Partners for Forever Families - Mandel School of Applied Social

advertisement