MI_Trainers_Slides - Motivational Interviewing for Behavior

advertisement

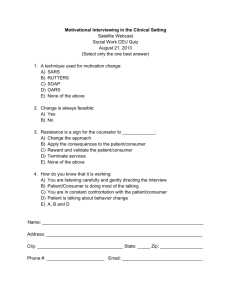

Welcome to… Motivational Interviewing for HIV/AIDS Prevention Programs For Bringing Hope (BH) and Abstinence & Be Faithful for Youth (ABY) Partners Facilitator: Trisha Long, University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill Task #1: Introduction* 1a. Think of an object which symbolizes your work (e.g., a tree, a helping hand, etc.). What is it, and why does it symbolize what you do? Share your symbol and something else about yourself with a partner. Time: 5 minutes 1b. We will hear everyone’s symbols as a group. Time: 10 minutes *Introduction exercise from Global Learning Partners 2 Why are we here? Goal of the BH and ABY programs: prevent new HIV/AIDS infections among youth and families. Delay sexual debut and increase abstinence in unmarried youth and adults. Increase faithfulness among married youth and adults. Build capacity of faith-based and community-based organizations to decrease transmission of HIV/AIDS. Reduce unhealthy sexual behaviors that increase people’s vulnerability to HIV.* Motivational Interviewing helps people change their behaviors It is useful when people are ambivalent about changing their behavior. It has been shown to be successful in a developing country setting when applied by non-professional counselors. *Goals adapted from the BH and ABY proposals 3 Part A: What is Motivational Interviewing? After completing Part A, you will have: Categorized people in various stages of change in Prochaska’s Model and related their situations to factors in Barrier Analysis; Compared an example of MI to an example of health promotion; Reviewed evidence of MI’s effectiveness; and Reflected on the key principles of MI and their relationship to development work, African culture, and your faith’s teaching. What are your questions? 4 Task #2: Identifying Barriers to Change 2a. The boxes on the next slide show scenarios of people in different stages of change – they are not in the correct order. Match the people in the scenarios with their stage of change. 2b. Based on your knowledge of Barrier Analysis, what are the determinants of behavior change for each of these people? Type in the determinants on the right, next to each person’s scenario. Time: 20 minutes 2c. We will hear a sample of your conclusions. 2d. At which stages of change do many development actions take place? Time: 20 minutes 5 Precontemplation Contemplation Preparation Action Maintenance Prudence is 18, and single. “It is such a relief to know that I will not have to worry about HIV. Since last month, when I made the decision to be abstinent until marriage, my heart feels light.” Behavior Change Determinants Benito is 17 years old and single. He has been having sex for the past three years, and does not see any reason why he should stop. He says, “Yeah, I’ve heard all about getting HIV, but if I am going to get HIV, I probably already have it by now.” Samuel is 25 and newly married. “I have decided I must be faithful to my wife. She and our future children mean too much to me to risk their health.” George is 40 years old, single, and has HIV. “I have just begun using a condom every time I have sex so that I will not infect my partners,” he says. “I hope I will be able to remember to buy them.” Jamila is 19 years old, and has been having sex for money in order to feed her younger siblings since age 15. “I would like to ask each man to use a condom so I know I am at less risk for HIV” she says, “but I do not think I could do it. Plus, I fear he will always refuse, and maybe become angry with me and hurt me.” 6 Precontemplation Contemplation Preparation Action Maintenance Mtume is 20 years old, and married for two years. “If I do not stop sleeping with other women,” he says, “I am sure I will bring HIV home to my family. But what will my friends say? Will they think I am less of a man if I only sleep with my wife?” Behavior Change Determinants Hasan is 24 years old. “Since I decided to be abstinent four months ago, I am happy with my decision,” he says. “Sometimes it is hard to wait, but I will be married soon, and my wife and I will be safe from HIV.” Safiya is 14 years old. “I have thought about this a lot,” she says. “I am ready to decide to be abstinent. I just need to know what I should tell my friends.” Amina is a 35, a wife and mother. “I haven’t heard much about HIV, but since I have always been faithful to my husband,” says Amina, “I could never get HIV. Besides, when God wants someone to get HIV, they get it.” Philip is 32, and married. “I don’t want my family to experience the stigma of HIV, even if I am not always faithful to my wife. I have decided to use a condom every time I have sex with another woman.” 7 Task #3: MI and Health Promotion: How different are they? 3a. Listen to the following examples of health promotion and motivational interviewing. Time: 15 minutes 3b. With a partner, name the differences between the two methods that you hear. Time: 5 minutes 3c. We will hear your ideas. Time: 20 minutes 8 MI and Health Promotion: Some Differences In MI, the person you are speaking to decides what you will talk about, not you. There is less direct confrontation or opposition. Strategies such as “importance scales” are used to enhance conversation Ask questions in a positive direction Good example: “Why is it somewhat important for you to change? Why is it more than just a little important?” Health promotion isn’t wrong or bad. It is not always the right tool for this situation. 9 Task #4: Evidence for the Effectiveness of MI 4a. Listen to the following presentations about how Motivational Interviewing has been used in an African context and to prevent HIV. Time: 15 minutes 10 Motivational Interviewing in Zambia From 1999-2001, MI was used in two peri-urban communities in Kitwe, Zambia, where diarrhea and clean drinking water had been identified as major concerns. The goal of the intervention was to encourage adoption of safe water storage practices and purchase of disinfectant in the target communities. 11 Health Promotion + MI Health promotion messages were delivered using MI by neighborhood health committee (NHC) volunteers in weekly visits that were 15-30 minutes long. An Intervention group received Motivational Interviewing along with education. A Comparison group received education only. 12 How NHC Volunteers Were Trained Only the volunteers using MI were trained in MI. All volunteers received diarrhea prevention and safe water education. Local nurses received training in MI, and then developed and delivered MI training for the Neighborhood Health Committee (NHC) volunteers. The NHC volunteers received approximately 10 hours of MI training. 13 Zambia MI Study, Field Trial #2: Bottles of Disinfectant Sold/HH (MI vs. Ed. Only), ’98-’99 Field Trial #3: Disinfectant Present in Stored Water 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% MI Control 1 Baseline Control 2 Follow-up 15 Field Trial #3: Ever Used Disinfectant 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% MI Control 1 Baseline Control 2 Follow-up 16 Field Trial #3: Know That Contaminated Water Causes Diarrhea 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% MI Control 1 Baseline Control 2 Follow-up 17 Field Trial #3: Believe They Can Avoid Diarrhea 95% 90% 85% 80% 75% 70% MI Control 1 Baseline Control 2 Follow-up 18 Field Trial #3: Know They Can Avoid Diarrhea by Boiling or Treating Water 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% MI Control 1 Baseline Follow-up Control 2 19 MI & HIV Prevention Two trials of an MI-based intervention for HIV risk reduction in a high-risk population in the U.S., conducted through community-based organizations. Study Population: Poor, single urban women, motivationally interviewed in groups Average age: 32 Education: Most did not complete secondary school Risky behaviors: Drug use, transactional sex, and multiple partners, already had a sexuallytransmitted disease 20 MI & HIV Prevention The immediate effects that were observed: Increased knowledge of HIV risk Stronger intentions to adopt safer sex practices Intentions communicated to sexual partners Fewer acts of unprotected sex These effects were mostly sustained at a three-month follow up. Effects were partially replicated in a second field trial, by a 4x increase in condom use in the MI Group. The MI Group women were also more likely to: Discuss HIV and condom use with partners Refuse unprotected sex Get an HIV test 21 Studies Cited Thevos A, Quick R, and Yanduli V. “Motivational Interviewing enhances the adoption of water disinfection practices in Zambia.” Health Promotion International. 2000; 15(3): 207-214. Thevos, A.K., Kaona, F. A. D., Siajunza, M.T., & Quick, R.E. “Adoption of safe water behaviors in Zambia: Comparing educational and motivational approaches.” Education for Health. (2000); 13(3): 366 - 376. Carey, M. and Lewis, B. “Motivational Strategies Can Enhance HIV Risk Reduction Programs.” AIDS and Behavior. 1999; 3(4): 269 – 276. 22 Important Limitations Few studies are in a developing-country context. No studies are available in which abstinence and faithfulness-based HIV prevention approaches were used. Most studies focus on risk reduction through condom use and increased risk awareness. Studies are often done with high-risk populations, such as commercial sex workers. 23 Why We Think MI Will Be Effective People are often ambivalent about sexual behaviors like abstinence, faithfulness, and condom use MI works best with ambivalent people People expect to be involved in making decisions about their sexual behavior MI respects this choice MI is not coercive 24 Other Situations Where MI has been Used to Help Individuals Change These are just a few examples: Alcohol and drug abuse in adults and teens Criminal rehabilitation Adherence to medication regimen or treatment Weight control Dietary changes related to health (example: lowering cholesterol) General healthcare settings, including emergency rooms at hospitals 25 Task #4: Evidence for the Effectiveness of MI 4b. What surprises you about the effectiveness of MI in these studies? 4c. What is different about the context of your project from how MI was used in these studies? 4d. What about these examples makes you confident that MI could be effective in your programs? 4e. How convinced are you of MI’s effectiveness at this point? Time: 15 minutes 26 4e. How convinced are you of MI’s effectiveness at this point? A: Very convinced B: Somewhat convinced C: Not sure D: Somewhat skeptical E: Not convinced 27 Task # 5: Principles of MI 5a. Read the following definition of Motivational Interviewing. Motivational Interviewing is a people-centered, directive method for increasing a person’s inner motivation to change by exploring and helping them to resolve ambivalence about a new behavior. What strikes you when you read this definition? Underline that part. What do you have questions about? Time: 15 minutes 28 Task #5 continued… 5b. Listen to the following presentation on motivational interviewing. Time: 15 minutes 29 The Guiding Values of MI Collaborating Together: honors the person’s experience and perspective. MI does not attempt to force someone to change. Bringing Forth Strength for Change: recognizes that the person already has the resources and motivation to change, and works to enhance them. We help people to “drink from their own wells.” Free Choice: respects the person’s right to decide what to do for themselves, and helps them make an informed decision. 30 Express Understanding Ambivalence is normal Use reflective listening We’ll practice this in Part B Accepting the person for who they are facilitates change This does not mean you must agree with or endorse their attitude or behavior “It is okay to feel confused about this issue.” 31 Develop Difference Change is motivated by perceived differences between present behavior and personal values or goals The person you are talking to discovers and presents their own arguments for change “For what I do is not the good I want to do; no, the evil I do not want to do--this I keep on doing.” [Romans 7:19] 32 Roll with Resistance Avoid arguing for change Instead, invite a new perspective on the issue Resistance is a signal to you to respond differently. We’ll talk more about this in Part B. “Take what you want and leave the rest.” (Who can argue with that?) 33 Support Self-Efficacy A person must believe they can change before change is possible. Self-efficacy: Barrier Analysis! People draw on hope and faith as personal resources for change Your belief in their ability to change can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. 34 Task #5 continued… 5c. Divide into three groups and reflect on the relationships between the values of MI, these principles and: Group 1: Development work Group 2: African culture Group 3: Your faith What examples of development interventions, African cultural beliefs or proverbs, and religious beliefs are supportive of the values and principles of motivational interviewing? Time: 20 minutes Time: 10 minutes 5d. We will hear all responses. 35 Review of Part A We related the Stages of Change to Barrier Analysis and discussed where MI fits in. We compared MI to Health Promotion. For what stages of change is MI helpful? What differences did you notice? We reviewed the evidence that MI can be effective in our context. We discussed the guiding values and principles of MI, and how they relate to development work, to African culture, and to religious faith. Do think MI is compatible with development work, with African culture, and with your faith? What are your questions? 36 Homework: Your Stories Think of two stories from your life where you were conflicted (ambivalent) about something. Specifics about the stories: You were trying to change something in your life (not someone else’s), either a behavior or a situation. There were good reasons to change, but also good reasons not to change. It is okay if you did not resolve the situation. The stories can be from any point in your life (they need not be recent). The story should not be so personal that you would be unwilling to share it with the other participants. Be able to finish telling the story in five minutes. We will tell each other our stories for one of tomorrow’s exercises. 37 Part B: Basic MI Skills After completing Part B, you will have: Examined an outline of the practice of Motivational Interviewing; Distinguished between open and closed questions; Assessed how reflective listening skills can help develop discrepancy between current behavior and personal values; Experienced, Heard, and Practiced reflective listening; Compared resistance and change talk as indicators of how the conversation is going; and Practiced using motivational interviewing skills in roleplaying situations. What are your questions? 38 Task #6: The MI Process 6a. Order the steps in the MI Process on the following diagram. Time: 10 minutes 39 Task #6: Order the MI Process Set the Agenda Explore Importance/ Values and Build Confidence Enhance Motivation to Change (Next: Create Change Plan) Open Questions Affirmation Reflective Listening Summarizing Exchange Information Reduce Resistance Encourage Change Talk Establish Rapport Assess how important they think change is, and how confident they are that they could change 40 The MI Process: An Overview Establish Rapport Assess importance and confidence Explore Importance/Values and Build Confidence Open Questions Affirmation Reflective Listening Summarizing Reduce Resistance Exchange Information Set the Agenda Encourage Change Talk Enhance Motivation to Change – Move on to Part 2, Creating a Change Plan 41 Task #6 continued… 6b. Looking at the MI diagram, what MI techniques could you use to increase someone’s feeling that it is important to change their behavior? 6c. What key determinants in Barrier Analysis affect importance the most? 6d. Thinking about the values and principles of MI, and OARS, how could you enhance confidence by using MI? 6e. How would low confidence affect importance of making a change? 6f. How did Afiya, the health promoter in yesterday’s scenario, assess Imani’s importance and confidence? Time: 20 minutes 42 Importance & confidence scales How important is it to you to remain abstinent before marriage? 1 2 Not important 3 4 5 Very important How confident are you that you can remain faithful to your spouse? 1 2 Not confident 3 4 5 Very confident 43 Preview of Part 2: Create a Change Plan Summarize arguments for change/acknowledge reluctance Ask a key question, like “What do you think you will do now?” Provide information and advice Set Goals Consider change options Make a Plan Elicit Commitment to the Plan Support Commitment to the Plan Review and Revise Plan, If Needed 44 Task #7: OARS - Open Questions 7a. Which is an open question? What do you think about abstaining from sex before marriage? OR Have you and your girlfriend discussed having sex? 45 Task 7 continued… 7b. With a partner, divide the following list into open and closed questions. Time: 5 minutes 7c. We’ll hear a sample of your responses. Time: 10 minutes 46 Categorize these questions as either: Open Closed What would make it easier for you to be faithful? Does your girlfriend ever ask you if you have other partners? Who decides whether or not you will use a condom, you or your partner? What consequences of HIV concern you most? What are the reasons that you would want to continue having sex with your boyfriend? What are your views on faithfulness in marriage? How would being abstinent before marriage be good for you? Have you ever been tested for HIV? Do you want to stay in this relationship? Is this an open or a closed question? Have you ever thought about being abstinent? Where do you go for information about HIV? Do you believe you can get HIV, even if you are married? What do you like about being abstinent? 47 Correct Answers Open Closed What do you like about being abstinent? How would being abstinent before marriage be good for you? What are your views on faithfulness in marriage? Where do you go for information about HIV? What consequences of HIV concern you most? What are the reasons that you would want to continue having sex with your boyfriend? What would make it easier for you to be faithful? Have you ever been tested for HIV? Have you ever thought about being abstinent? Do you want to stay in this relationship? Do you believe you can get HIV, even if you are married? Does your girlfriend ever ask you if you have other partners? Who decides whether or not you will use a condom, you or your partner? Is this an open or a closed question? 48 Task #8: Recognizing OARS 8a. Listen to the following dialogue, which shows the use of open questions, affirmation, reflective listening, and summarizing in developing discrepancy. 8b. Circle or mark the following in your paper copy of the dialogue: Two examples of reflective listening One open question One example of resistance One example of affirmation One example of summarizing 8c. We will hear your responses. Time: 30 minutes 49 Affirmation An affirmation is a compliment! Praise positive behaviors. Support the person as they describe difficult situations. Examples: “You seem to be a very giving person. You are always helping your friends.” “That situation must have been very painful for you, but you managed to get through it.” 50 Simple Reflections Repeat back what the person said. This is the same as paraphrasing. Condense your response so that it is shorter than what they said. These are statements, not questions. You can reflect emotions, too. If you want to move the conversation along, add something – take a chance! Examples: “You had a difficult time confronting your wife about her infidelity, and now you don’t know how to approach her.” “Your mother is really concerned that you will get pregnant before you finish school.” 51 Amplified Reflections Strengthen what the person said as you reflect it. You can make sure you understood. If their statement was extreme, you can see if they really meant it. If the amplified reflection was too strong or not correct, the person will tell you. Examples: “It wouldn’t matter at all if you got AIDS.” “It would be impossible for you to be abstinent.” 52 Double-sided Reflection A double-sided reflection gives both sides of the argument. You’ve heard arguments for and against change, or you’ve heard two sides of something. Use “and” or “but” depending on how you want to proceed in the conversation. “And” is less confrontational – use “and” if you are hearing resistance. “But” emphasizes the last thing you say – “but” may cause resistance, so use it with caution! Examples: “You know your friends will not approve, but you also know that your parents and your church will approve.” “Some days it seems as though you will never get out of this trap, and some days give you hope that things really could change.” 53 Summarizing Make a summary statement that encompasses everything that was said. Summarizing can be helpful when you want to move in a new direction. Examples: “This has been a really difficult year for you. You have traveled a great deal, and it has not been easy to keep your marriage vows when you are away for so long.” “You are feeling a lot of pressure to have sex with this man. He offers you money for nice clothes, to pay your school fees, and for other things that you want. Your parents won’t object. You don’t want to do it, but you feel trapped.” 54 Being Directive You choose what you reflect from a discussion. Being directive helps you move the conversation toward talking about change. How to choose? Listen carefully. What are you curious about? Did you hear a desire to change? An idea of how to change? Follow up on these things! 55 Task #9: Using the OARS 9a. Divide into groups of three. Storyteller: tell one of the stories you came up with for homework Pause after every 2-3 statements to give the other person a chance to listen reflectively. Reflective Listener: listen reflectively using OARS as they tell their story Coach: observe the conversation and take notes on the reflective listener; make notes of both good technique and areas for improvement. 9b. After the story is complete, the storyteller and the coach provide feedback to the reflective listener. (5 minutes) 9c. Switch positions and repeat until everyone has had an opportunity to listen reflectively at least once. Time: 1 hour If you have extra time, tell your 2nd story! 56 Task 9 continued… How did you feel when you were ‘reflectively listened to’? What good tips did you hear from your coach and storyteller? What did you notice about reflective listening when you were observing it? 57 Change Talk & Resistance in MI Change Talk is like a green traffic signal: it tells you to keep moving forward! Resistance is like a red traffic signal: it tells to stop what you are doing! 58 Task #10: Recognizing Resistance to Behavior Change 10a. You will see examples of different responses to a single question. Using your voting buttons, vote on whether the responses are examples of resistance or not. = Yes, it is resistance. X = No, it is not resistance. Time: 30 minutes 59 Task # 10: Is it resistance? Question: “So what do you think about abstinence before marriage?” Response: “I don’t think it really matters if you’re abstinent or not. That’s a very old-fashioned view.” = yes, X = no 60 Task # 10: Is it resistance? Question: “So what do you think about abstinence before marriage?” Response: “Well, sometimes it’s just not that easy.” = yes, X = no 61 Task # 10: Is it resistance? Question: “So what do you think about abstinence before marriage?” Response: “...Nothing, really.” = yes, X = no 62 Task # 10: Is it resistance? Question: “Let’s talk a little more about abstinence. So what do you think about-” Response: “I’d rather talk about my boyfriend.” = yes, X = no 63 Task #10: Is it resistance? All were examples of resistance. Sometimes resistance is not an outright challenge or denial – it can be subtle. What to do? Roll with resistance. Christ give us an MI idea: “But I tell you, Do not resist an evil person. If someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also.” [Matthew 5:39] In other words, don’t argue back. 64 Task #10 continued 10b. What skills have you already learned which might help you roll with resistance? 10c. What resistance to abstinence and faithfulness might you expect to hear from participants in the BH and ABY projects? 65 Shifting Focus Resistant Statement: “I suppose now you are going to tell me I can never have sex again until I am married.” Shifting focus: Go around the barrier, not over it. Example: “We’ve only just begun to discuss this, and you are right - we should not jump to any conclusions about what you’ll want to do.” 66 Reframing Resistant Statement: “I suppose now you are going to tell me I can never have sex again until I am married.” Reframing: Acknowledge validity, but interpret differently. Example: “It’s hard to imagine going without something like sex for what could be a long time, you’re right. There are benefits to sex, definitely, and there are also benefits to abstinence: you can protect yourself and your future spouse from HIV. 67 Agree with a Twist or Emphasize Personal Control Resistant Statement: “I suppose now you are going to tell me I can never have sex again until I am married.” Agree with a twist: Reflect, and then reframe the discussion “You’re wondering how difficult it would be for you to abstain from something that’s really fun, even if it would protect you from AIDS.” Emphasizing personal control: Example: “This is your decision. Even if I wanted to, I could not make it for you.” 68 “Coming Alongside” Resistant Statement: “I suppose now you are going to tell me I can never have sex again until I am married.” Coming alongside: Take on the anti-change point of view: Example: “It may be difficult for you to abstain. Maybe it’s worth the risk of getting HIV to continue on as you are.” Use with caution! Now we’ll hear some more examples of each of these… 69 Task #11: Practice Rolling with Resistance 11a. Using the examples of resistance that we developed in the last exercise, write two responses using the methods of rolling with resistance that we just discussed. Use a different method of rolling with resistance for each of your responses. Time: 10 minutes 11b. We will hear all responses. Time: 5 minutes 70 Change Talk in MI Change Talk is like a green traffic signal: it tells you to keep moving forward! Listen for Change Talk and encourage it! 71 4 Kinds of Change Talk Disadvantages of Maintaining the Behavior Advantages of Change “It would be wonderful to be married and know for sure that my wife and I will not have HIV.” Optimism about Change “When I am unfaithful, my wife suspects it, becomes angry, and then we argue.” “I think I could do it if I tried, and if I convinced some friends to try it too.” Intention to Change “I think I could at least limit my sexual partners so that I only had one girlfriend at a time.” 72 Task #12: Encouraging Change Talk 12a. Listen to the following conversations. Count the number of times you hear change talk. 12b. How might you use the importance/confidence ruler to encourage change talk? Time: 5 minutes 12c. What other ways might you encourage change talk? Write down three examples. Time: 15 minutes 12d. We will hear all examples. Time: 10 minutes 73 Eliciting Change Talk Open questions: What worries you about having sex with your girlfriend now? If you did decide to be abstinent, what would be good about it? If you resolved to be faithful to your spouse, what about you makes you think you could be successful? So what are you thinking about abstinence at this point? 74 Eliciting Change Talk Asking for more details In what ways do you think your friends would support your decision to be abstinent? You mentioned there was a time when you were tempted to sleep with someone else, but you didn’t. Tell me more about that time, and your reasons for avoiding infidelity. What other difficult decisions have you made in your life? How did you make them? 75 Eliciting Change Talk Ask about extreme situations: What is your biggest concern about AIDS in the long run? What consequences of having sex with many partners do you know of, even if you don’t think they could happen to you? If you were completely successful at being abstinent until marriage, what positive things would happen? 76 Eliciting Change Talk Explore the past and the future Before you had these worries about HIV, what was your life like? If you continue on as you are now, what do you think will happen? Tell me what life will be like for you in five years. Think back to when you were first married. How did you feel about your marriage and your spouse? How would you like things to be in your future? Tell me about the best possible future you can imagine. 77 Eliciting Change Talk Goals and Values What is most important to you in your marriage? What do you think people should do about sex before marriage? What do you think God wants people to do about their sexuality within marriage? What do you value in a spouse? What are the qualities that you would want for yourself? What do you think is the right thing to do about faithfulness in marriage? 78 Remember your OARS! You can Ask Open Questions about change Affirm change talk Reflect change talk Summarize reasons for change 79 A Little Motivation If you are working skillfully, you should be able to stop in the middle of a conversation and have a sense of what you are doing, why, and how the person is reacting… This does not mean that the conversation should be full of flawless promises to change behavior. Indeed, you both might be very confused…But you should at least be aware that this is happening, and have a sense of where to go next in the conversation. You do not need to have all the answers…If confused, you can sometimes be frank with the person to remarkably good effect. Paraphrased from “Health Behavior Change”, by Rollnick, Mason, and Butler, p. 134. 80 Task #13: Practice Motivational Interviewing! 13a. In pairs, practice your motivational interviewing skills. One: Assume a character who is being motivationally interviewed: you will be given information about your character, or you may make up your own. Two: Practice the motivational interviewing skills we have been learning. Take 30 minutes for your first conversation, debrief for 5 minutes after, then switch roles. Time: 2 hours, or until end of day 81 Task # 13: Guidance Characters: Remember you are ambivalent! Do not be so resistant that your interviewer has no chance at all! Do not be too easy on your interviewer, either: you should not resolve your character’s ambivalence today. What skills do you want to practice? Give them the opportunity to practice those, too. Interviewers: You will not resolve the problem today. In real life, you could have many conversations before a person is ready to consider change. Expect this, listen to your partner, and respond accordingly. Go at your partner’s pace. Do not attempt to rush the conversation just because you are practicing. 82 Review of Part B We examined an outline of the practice of Motivational Interviewing. We distinguished between open and closed questions. What is the most difficult part of the process, in your opinion? What is an open question? We assessed how reflective listening skills can help develop discrepancy between current behavior and personal values. What does the acronym OARS stand for? 83 Review: The MI Process Establish Rapport Assess importance and confidence Explore Importance/Values and Build Confidence Open Questions Affirmation Reflective Listening Summarizing Reduce Resistance Exchange Information Set the Agenda Encourage Change Talk Enhance Motivation to Change – Move on to Part 2, Creating a Change Plan 84 Review of Part B, cont… We experienced, heard, and practiced reflective listening. We compared resistance and change talk as indicators of how the conversation is going. Name one kind of reflection that we talked about. What are the four kinds of change talk? We practiced using motivational interviewing skills in role-playing situations. How confident do you feel in your ability to motivationally interview someone? To teach others to use MI? 85 Review: Guiding Values of MI Collaborating Together: honors the person’s experience and perspective. MI does not attempt to force someone to change. Bringing Forth Strength for Change: recognizes that the person already has the resources and motivation to change, and works to enhance them. We help people to “drink from their own wells.” Free Choice: respects the person’s right to decide what to do for themselves, and helps them make an informed decision. 86 Review: Principles of MI Express Understanding Develop Difference Explore differences between personal values, goals and current behavior Roll with Resistance Ambivalence is normal Avoid arguing with the person Support Self-Efficacy A person must believe they can change before change is possible 87 Part C: Change, Special Cases, and Problems After completing Part C, you will have: Ordered the steps in creating a plan for change; Listed and examined special groups with whom your learners are likely to work; Heard the specific ways in which MI can be adapted to work with special groups; Reviewed common problems in using MI and identified how to avoid them using MI skills. What are your questions? 88 Task #14: Recognizing Readiness for Change 14a. Look at this list of behaviors. Circle those which may indicate that a person is ready to change. Time: 5 minutes 14b. We will hear examples of your choices. 14c. Which ones surprise you? Time: 10 minutes 89 Task # 14: Which Ones Indicate a Person is Ready to Change? Asking about change Trying out a change behavior Arguing against change Feeling a sense of loss and resignation Increased talk about the problem Feeling peaceful and calm Imagining difficulties if a change were made Blaming others for the problem Discussing the advantages of change Expressing hope for the future Saying the problem isn’t that bad 90 Task # 14: Which Ones Indicate a Person is Ready to Change? Asking about change Trying out a change behavior Arguing against change Feeling a sense of loss and resignation Increased talk about the problem Feeling peaceful and calm Imagining difficulties if a change were made Blaming others for the problem Discussing the advantages of change Expressing hope for the future Saying the problem isn’t that bad 91 Task #15: Creating a Plan for Change 15a. Order the steps in creating a plan for change. Time: 15 minutes 15b. We will hear your ideas. Time: 15 minutes 92 Task #15: How would your order these steps in creating a plan for change? Consider change options Summarize arguments for change/acknowledge reluctance Set Goals Make a plan Elicit Commitment to the Plan Ask a key question, like “What do you think you will do now?” 93 Task #15: Creating a plan for change Summarize arguments for change/acknowledge reluctance Ask a key question, like “What do you think you will do now?” Provide information and advice Set Goals Consider change options Make a plan Elicit Commitment to the Plan Support Commitment to the Plan Review and Revise Plan, If Needed 94 Summarizing Arguments for Change Your summary should include: The person’s own perceptions of the behavior, reflected in their change talk (disadvantages of status quo) Acknowledgement of what is attractive about the behavior Review of any objective evidence that is relevant to the importance of change Restatement of any change talk about intention to change, and confidence in his or her ability to change Your own assessment of the person’s situation, especially when it is similar to their own. 95 Task #15: Creating a Plan for Change 15c. Write two examples of key questions. 15d. We will hear all questions. 96 Ask a Key Question More key question examples: Where does this leave you? What is your next step? What are your options? How do you want things to be for you in the future? Of the things we have talked about, what concerns you most? What do you want to do? It sounds like things cannot stay the way they are now. What do you think you might do? 97 Set Goals for Change Goals are the choice of the person who must fulfill them: Don’t try to set goals for the person Suggest additional goals or milestones, after asking for permission to do so Prioritize multiple goals together – use your OARS to help the person decide what they need to do immediately, and what they can address later People may not set goals which are realistic for themselves Ask them to rate their confidence in their ability to achieve the goal Ask them to consider the consequences of an action 98 Consider Options & Make a Plan Create a “menu” of options for change Ask for their ideas on how they could change Discuss ways in which other people have changed Do not impose your own views, or others’ views about how to change on the person Make a plan for change Help them verbalize the plan Write down their plan, if appropriate Suggest a ‘trial run’ of the plan Summarize the whole plan 99 Elicit Commitment to the Plan Another key question: “Is this what you want to do?” You hope they will say “Yes.” If they seem reluctant, do not push them into saying yes. Ask them to think and pray about it until your next meeting. Emphasize personal choice again. 100 Giving Advice and Information Before you give unsolicited advice or information: Ask yourself: Have I asked the person what he or she thinks about this subject? Is the information I will give important to the person’s safety or likely to enhance their motivation to change? Ask the person’s permission If they ask you for more information or for your opinion, share it with them in a thoughtful, sensitive manner. 101 Task #15: Creating a Plan for Change 15e. Listen to the following roleplay demonstrating all the steps in Part 2 of MI. Time: 10 minutes 102 Task # 16: Working with special groups 16a. Look at the following list of special groups with whom you and your motivational interviewing trainees are likely to work. These came from the survey you answered prior to this training. 16b. In groups of three, list other people you or your trainees will work with that you do not see here. Time: 15 minutes 103 Task # 16: Who will you work with? Youth Mothers Family and friends Who else? 104 Tips for working with youth Not much research published with MI and youth in general Even less research done with MI and youth who have already initiated risky behavior These youth have often had negative experiences with adults which may cause them to be more resistant to change Rapport is therefore even more important If you are an authority figure, show them you are different from other authority figures they have encountered: acknowledge their doubts, and then show them with MI that you are not here to give the same old message Spend the time necessary to develop an alliance before asking permission to give advice or feedback 105 Tips for working with groups Groups amplify behavior: people may take strong positions or not speak because they are among peers Just because you won’t try to ‘fix it’ doesn’t mean others won’t: Set ground rules: help them feel safe Be careful to reframe inappropriate comments, emphasizing personal control Use demands for answers as opportunities for group reflection Solutions emerge from the group, not the facilitator 106 Group construction…some tips 10-20 people per homogenous group seems ideal With more people, there is a lot to do - consider two group leaders: Discuss how you will work together You might divide tasks: e.g., rolling with resistance and expressing empathy May facilitate breaking up into smaller groups If possible, don’t overload the group with people who are not considering change Try an exercise to see who is thinking about change and who isn’t Use your own judgment when forming groups: would it be advantageous to include some people who have successfully changed? 107 Tips for working with couples MI may be used with couples together when both partners will support change neither will hinder it In some situations it may be better to pursue MI individually Example: a discussion of faithfulness will not cause one partner to accuse the other of being unfaithful Example: discussion of a spouse’s unfaithfulness in front of their partner would threaten that person’s physical safety Couples can be taught to use motivational interviewing skills (example: OARS) with each other to overcome difficulties in communicating 108 Task #16: Special groups continued 16c. Based on your own experience working with these groups or types of people on other projects, what advice do you think might be helpful for using motivational interviewing with them? 109 Task #17: Who’s thinking about change? 17a. Imagine that you are a youth group leader using MI techniques to discuss abstinence. In your groups of three, design an activity that would tell you how many people in a group are considering abstinence before marriage, and how many are not. Your activity should take no more than 5 minutes to complete Think about how to adapt your activity for our online environment. Time: 15 minutes 17b. We will participate in your activities! Time: 15 minutes 110 Task #18: Avoiding the traps! 18a. You will see examples of what not to do in motivational interviewing! Time: 5 minutes 111 Early Traps: Labeling Raina: So you have been prostituting yourself. Sophie: He just pays my school fees. It’s not the same. Labels like “prostitute” and “promiscuous” may increase resistance, and decrease desire to talk about the behavior in question. There is no reason to use them. 112 Early Traps: Blaming Emerson: Even if your wife doesn’t seem interested, is it permissible to sleep with others? Jacob: So it’s all my fault. She has nothing to do with it. Blaming serves no purpose in motivational interviewing, and often increases resistance, no matter who is being blamed. 113 More Traps: Gloom for Two Sophie: What can I do? I have to sleep with him – my family has no money, certainly none for school fees. This is the only way I can go to school. Besides, my parents are happy with this arrangement: they think I am a connection with someone influential. Raina: Wow, that’s awful. [really depressed] At least one of you has to have hope! Be empathetic, and use your faith to lend hope to the other person. This does not mean you must be unrealistically cheerful. 114 Review of Part C We ordered the steps in creating a plan for change; List the steps in creating a change plan. We listed and examined special groups with whom your learners are likely to work; We heard the specific ways in which MI can be adapted to work with special groups; What are some tips for using MI with the groups we discussed? We reviewed common problems in using MI. What are the three traps we reviewed? What are your questions? 115 The Final Quiz You will see these types of questions: Questions which ask you to identify a component of motivational interviewing, or to describe it. (multiple choice and short answer) Questions which present a short MI conversation and ask you: “What is happening here which should not happen in MI?” (multiple choice) Questions which ask you to recover from a mistake made by a motivational interviewer (e.g., arguing with the person they are interviewing): “How would you respond?” (short answer) – Remember that there may be more than one correct way to respond. Questions which ask you to demonstrate how to respond to a person using motivational interviewing: “How would you respond?” (short answer) – Remember that there may be more than one correct way to respond. 116