Chapter 10 - Routledge

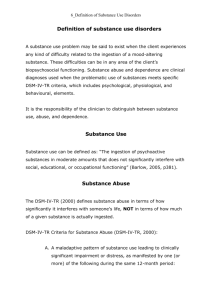

advertisement

Chapter 10 The psychology of exercise for clinical populations Exercise can be good for you even when you are ill Exercise was invented and used to clean the body when it was too full of harmful things. Christobal Mendez, 1500–1561 (Berryman 2000). Chapter 10: Aims • highlight the psychological issues associated with exercise for clinical populations • use the American College of Sports Medicine’s framework for classifying disease and disability • provide examples of psychological issues for each category in the ACSM framework • summarise what we know in this area of exercise psychology • offer a guide to good practice • provide recommendations for conducting research in exercise psychology with clinical populations Patients (n=70) 10.1 Flow of participants through trial for Type 2 diabetics Kirk et al. 2004b Baseline assessments Physical activity (7-day recall, CSA activity monitor) Glycaemic control (HbA1c, medication) Cardiovascular risk factors (Body Mass Index, blood pressure, lipid profile) Exercise consultation & standard exercise leaflet (n=35) Standard exercise leaflet alone (n=35) 6 month assessment Repeat baseline assessments Exercise consultation & standard exercise leaflet (n=32) Standard exercise leaflet alone (n=31) 12 month assessment Repeat baseline assessments Experimental group (n=31) Control group (n=29) 10. 2 Increases in objectively measured physical activity following physical activity counselling. Kirk et al. 2004b 4000000 *28% increase Experimental group Total activity counts/week 3500000 *15% increase 3000000 2500000 *12% decrease *20% decrease 2000000 Control group 1500000 Baseline 6 months 12 months 10.3 Improvements in glycaemic control following physical activity counselling. Kirk et al 2004a Experimental group Change from baseline to 12 months Control group 0.34% increase 0.27% decrease Change from baseline to 6 months 0.15% increase 0.26% decrease Non diabetic range 4-6% -0.4 -0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0 0.1 0.2 Improving HbA1c (%) Deteriorating 0.3 0.4 10.4 Improvements in cardiovascular risk factors following physical activity counselling. Kirk et al. 2004a Systolic blood pressure 6 Change in cholesterol (mmol/L) Change in blood pressure (mmHg) Total cholesterol 0.1 0.05 4 + 5.0 mmHg 2 + 0.04 mmol/L 0 -0.05 0 -2 -0.1 -0.15 - 6.3 mmHg - 0.32 mmol/L -0.2 -4 -0.25 -6 -0.3 -8 Experimental group Control group -0.35 Experimental group Control group 10.5 Pilot study - exercise as rehabilitation during breast cancer treatment.Campbell et al. 2005 80 70 60 % change 50 40 over 12 30 weeks 20 10 0 -10 78 32 15 -1 7 day recall of PA 1 -1 12 min walk Quality of life test usual care exercise Exercise dependence pages 270 -277 Confusing terminology: negative addiction, obligatory exerciser, compulsive exerciser. Exercise dependence has the only stated diagnostic criteria and so it is the preferred term Dependence occurs when exercise causes people to be unable to function in personal relationships, work life or health. Distinction between primary and secondary dependence (eg secondary to eating disorders or muscle dysmorphia) ICD-10 classification of dependence syndrome WHO 1993 Classification Compulsion Impaired control Withdrawal Relief use Tolerance Salience Dependence syndrome Desire/compulsion to take the substance Difficulty in controlling behaviour in regard to onset, termination and level of substance taking Physiological withdrawal states occurs when substance withdrawn Substance used to avoid or relieve withdrawal symptoms Increased amount of substance required to achieve effect similar to lower dose Increased amounts of time spent in obtaining or taking substance or recovering from its effects. Persistence despite awareness of harmful response Criteria for exercise dependence Veale, (1987). Exercise dependence. British Journal of Addiction, 82, 735-740. Criteria A Narrowing of repertoire leading to a stereotyped pattern of exercise with a regular schedule once or more daily Impaired control B Salience with the individual giving increasing priority over other activities to maintain the pattern of exercise salience C Increased tolerance to the amount of exercise performed over the years tolerance D Withdrawal symptoms related to a disorder of mood following the cessation of the exercise schedule withdrawal E Relief or avoidance of withdrawal symptoms by further exercise Relief compulsion F Subjective awareness of the compulsion to exercise G Rapid re-instatement of the previous pattern of exercise and withdrawal Impaired control symptoms after a period of abstinence Criteria for exercise dependence continued Associated features H Either the individual continues to exercise despite a serious physical disorder known to be caused, aggravated or prolonged by exercise and is advised as such by a health professional, or the individual has arguments or difficulties with his/her partner, family, friends, or occupation I Self-inflicted loss of weight by dieting as a means towards improving performance Raising awareness of exercise dependence • Do you think exercise is compulsive for you? • Is exercise the most important priority in your life? • Is your exercise pattern very routine and rigid? Could people ‘set their watches’ by your exercise patterns? • Are you doing more exercise this year than you did last year to gain that feel good effect? • Do you exercise against medical advice or when injured? • Do you get irritable and intolerable when you miss exercise and quickly get back to your exercise routine if you are forced to change it? • Have you ever considered that you were risking your job, your personal life or your health by overdoing your exercise? • Have you ever tried to lose weight just to make your exercise performance better? If you answered YES to most of these questions, or if you are worried about becoming dependent on exercise please speak to a member of staff or follow these self- help strategies: use cross-training to avoid over use injuries, remember aerobic fitness, strength and flexibility are all important aspects of fitness schedule a reasonable rest period between two bouts of exercise to prevent mental and physical fatigue schedule one complete rest day each week and notice how energetic you feel the next day exercise your mind by getting involved in mental and social activities that can lower anxiety and lift selfesteem try to learn a stress management technique such as relaxation, yoga, tai chi or meditation Exercise dependence is characterised by: • a frequency of at least one exercise session per day • a stereotypical daily or weekly pattern of exercise • recognition of exercise being compulsive and of withdrawal symptoms if there is an interruption to the normal routine • reinstatement of the normal pattern within one or two days of a stoppage Exercise dependence as secondary to eating disorders • What are the common eating disorders? – Anorexia nervosa (body image of ‘fat’ even when very thin, starvation, can be fatal, associated with hyperactivity) – Bulimia nervosa (binge eating, use of laxatives, vomiting and exercise to ‘cleanse’, may look normal, but feels fat) • These eating disorders affect more women than men • Exercise is secondary to these conditions • Exercise can be successfully used in treatment programmes Exercise dependence secondary to muscle dysmorphia [reverse anorexia] Pope et al (1997) Psychosomatics, 38,548-57 • Body dysmorphic disorder is a mental illness – eg hating a leg and wishing it to be amputated • muscle dysmorphia is a pathological preoccupation with the whole body – perception of insufficient muscularity – lives consumed by weightlifting and other exercise, nutrition and perhaps drug abuse – affects both genders more common in men Muscle dysmorphia consequences • Profound distress about body being seen in public • impaired social and work functioning • anabolic steroid and other drug abuse • it is rare but more prevalent in the weight training fraternity • Diagnostic questionnaire recently developed • recent phenomenon- why? Could athletes training for a competition be exercise dependent ? Possible answers? • Yes – If athletes feel compelled to train in systematic way against medical advice, or despite personal or work problems. • No – If volume of training required for performance • Awareness needed – Could be a pre-cursor to overtraining and so awareness of exercise dependence needs to be raised amongst athletes and coaches as well as exercise leaders Subclinical eating disorders in athletes • What sports are most likely to create disordered eating with a view to weight loss or gain? • Sports that require lean athletes: long distance running, gymnastics, ballet • weight category sports: judo, jockeys, boxing • weight advantage sports: sumo wrestling • coaches and sport scientists must be aware of these issues and avoid poor eating patterns becoming serious disorders Why does exercise dependence occur? • No clear answer • Suggestions include: – – – – – – – – Obessive-compulsive disorder ‘running away’ from other problems Low self-esteem High anxiety levels Addicted to ‘endorphins’etc Sympathetic arousal hypothesis Analogue to eating disorders Cultural pressure ACSM (1977) ACSM’s exercise management for persons with chronic diseases and disabilities • cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases • metabolic diseases • immunological and haematological disorders • orthopaedic diseases and disabilities • neuromuscular disorders • cognitive, emotional and sensory disorders Recommendations for research with clinical populations • • • • • • • • • Researchers should form links with medical teams dealing with specific conditions. Qualitative research may often provide a starting point for such research because many of the situations do not lend themselves to standard clinical trials. Explore a variety of programmes such as home-, community- and hospitalbased or combinations of these. Both researchers and practitioners should operate with a model of behaviour change to guide them. Activity must be recorded before and after any exercise programme or intervention. Report the uptake for any exercise programme from the potential client population. Investigate motivations and barriers to exercise in each patient group as a whole and also for those who have taken up the offer or completed an exercise programme. Record and report (via a register or via contact) adherence at regular intervals Report adherence to exercise prescription as a percentage of target in as many ways as possible Key point: • It is important to apply principles of exercise psychology to clinical populations because quality of life is an important outcome from exercise and long-term adherence is beneficial to these patient groups. Key point: • The long-term goal for exercise specialists working with patient populations is to assist them in becoming independent exercisers. Key point: • Maintaining regular activity after supervised hospital-based programmes is difficult for cardiac rehabilitation patients and requires urgent attention from exercise psychology research. Key point: • Treating obesity and preventing weight gain through physical activity requires two or three times more activity (for example, up to ninety minutes) than the amount of activity required for health. This is a challenge for participants and exercise psychologists. Key point. • Exercise psychology could help construct a movement education programme for those suffering from back pain that increases patients confidence that they can move in a pain-free way. Key point • Schizophrenic patients report benefit from exercise and further research on this patient group should explore what kind of exercise and what dose of exercise is best. Key point: • Evidence suggests that problem drinkers can benefit from exercise programmes in terms of physical outcomes. However, evidence for mental health benefits or any advantage to reducing alcohol intake is weaker. Key point: • Dependence is a potentially serious negative consequence from exercise. However, there is no known prevalence of this problem. Key point: • Physical activity and exercise affect how we think and feel – this is known as the somatopsychic process. Exercise- associated mood alterations: A review of interactive neurobiologic mechanism” LaForge, R. (1995).Medicine, Exercise, Nutrition and Health, 4, 17-32 • Best review of neurobiological mechanisms • Integrates processes • All mechanisms overlap in structure and function and in terms of neuro-atomic pathways • Latest imaging technologies will enhance what is happening in the exerciser’s brain Plausible mechanisms: Neurobiological processes involved in positive mood Opponent process theory Opioids Monoamines Neocortical activation Thermogenic changes HPA axis Synergistic conclusion La Forge “ The mechanism is likely an extraordinary synergy of biological transactions, including genetic, environmental, and acute & adaptive neurobiological processes. Inevitably, the final answers will emerge from a similar synergy of researchers and theoreticians from exercise science, cognitive science and neurobiology” Chapter 10: Conclusions 1 • • • • • • • Patients in almost all categories of disease and disability could benefit from exercise. There are few contraindications. Knowledge about adherence and psychological outcomes is incomplete. The area of cardiac rehabilitation offers the most information on adherence. Good short-term adherence (4-12 weeks) can be achieved from supervised programmes of exercise Some populations, such as those in drug rehabilitation or those with HIV + status, even short-term adherence may need special support systems. Long term adherence (12 months - 4 years) is poor and not well documented. Home-based walking programmes seem to offer the best hope for long term adherence but other modalities must be explored. Very little is known about the level of exercise in clinical populations. Chapter 10: Conclusions 2 • • • • • • • • Drop-out from exercise programmes is associated with factors to do with the programme and factors to do with the person and his/her circumstances Motivations for exercise are clearly to do with improved health. Barriers to exercise are similar to non-clinical populations (e.g., lack of time) but also include issues to do with the particular disease state. Cognitive behavioural strategies can be effective and the use of a counselling approach should be encouraged in all clinical settings. Psychological outcomes are often mentioned anecdotally but are rarely measured in exercise programmes or interventions. The potential psychological benefits range from increasing a person’s sense of confidence, control and self-esteem, improving mood, increasing social opportunities, improving cognitive function, and improving quality of life. There is a need for raising awareness in some medical teams concerning the role of exercise, the potential psychological benefits and the need to assist patients with adherence to exercise. Exercise dependence is a potentially harmful outcome from exercise but the prevalence is not known. Exercise dependence secondary to eating disorders or muscle dysmorphia may be more common than primary exercise dependence There is no clear consensus about the mechanisms that could explain the psychological benefits experienced from physical activity. New technology may offer greater understanding of this topic in the near future