Day28_CFL-Decisions_TM-Intro - Rose

advertisement

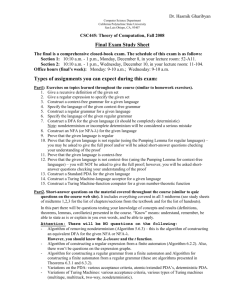

MA/CSSE 474

Theory of Computation

TM Design

Universal TM

Your Questions?

• Previous class days'

material

• Reading Assignments

• HW 12 problems

• Anything else

I have included some

slides online that we will

not have time to do in

class, but may be helpful

to you anyway.

The CFL Hierarchy

Context-Free Languages Over

a Single-Letter Alphabet

Theorem: Any context-free language over a single-letter

alphabet is regular.

Proof: Requires Parikh’s Theorem, which we are

skipping

Algorithms and Decision

Procedures for

Context-Free Languages

Chapter 14

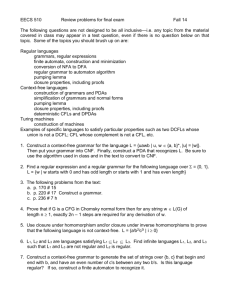

Decision Procedures for CFLs

Membership: Given a language L and a string w, is w in L?

Two approaches:

● If L is context-free, then there exists some context-free

grammar G that generates it. Try derivations in G and see

whether any of them generates w.

Problem (later slide):

● If

L is context-free, then there exists some PDA M that

accepts it. Run M on w.

Problem (later slide):

Decision Procedures for CFLs

Membership: Given a language L and a string w, is w in L?

Two approaches:

● If L is context-free, then there exists some context-free

grammar G that generates it. Try derivations in G and see

whether any of them generates w.

S ST|a

Try to derive aaa

S

S

S

T

T

Decision Procedures for CFLs

Membership: Given a language L and a string w, is w in L?

● If

L is context-free, then there exists some PDA M that

accepts it. Run M on w.

Problem:

Using a Grammar

decideCFLusingGrammar(L: CFL, w: string) =

1. If given a PDA, build G so that L(G) = L(M).

2. If w = then if SG is nullable then accept, else reject.

3. If w then:

3.1 Construct G in Chomsky normal form such that

L(G) = L(G) – {}.

3.2 If G derives w, it does so in 2|w| - 1 steps. Try all

derivations in G of 2|w| - 1 steps. If one of them

derives w, accept. Otherwise reject.

Alternative O(n3) algorithm: CKY

Membership Using a PDA

Recall CFGtoPDAtopdown, which built:

M = ({p, q}, , V, , p, {q}), where contains:

● The start-up transition ((p, , ), (q, S)).

● For each rule X s1s2…sn. in R, the transition ((q, , X), (q,

s1s2…sn)).

● For each character c , the transition ((q, c, c), (q, )).

Can we make this work so there are no -transitions? If every

transition consumes an input character then M would have to

halt after |w| steps.

Put the grammar into Greibach Normal form:

All rules are of the following form:

● X a A, where a and A (V - )*.

We can combime pushing the RHS of the production with

matching the first character a. Details on p 316-317.

Greibach Normal Form

All rules are of the following form:

●X

a A, where a and A (V - )*.

No need to push the a and then immediately pop it.

So M = ({p, q}, , V, , p, {q}), where contains:

1. The start-up transitions:

For each rule S cs2…sn, the transition:

((p, c, ), (q, s2…sn)).

2. For each rule X cs2…sn (where c and s2

through sn are elements of V - ), the transition:

((q, c, X), (q, s2…sn))

A PDA Without -Transitions Must Halt

Consider the execution of M on input w:

● Each

individual path of M must halt within |w| steps.

● The

total number of paths pursued by M must be

less than or equal to P = B|w|, where B is the

maximum number of competing transitions from

any state in M.

● The

total number of steps that will be executed by

all paths of M is bounded by P |w|.

So all paths must eventually halt.

Emptiness

Given a context-free language L, is L = ?

decideCFLempty(G: context-free grammar) =

1. Let G = removeunproductive(G).

2. If S is not present in G then return True

else return False.

Finiteness

Given a context-free language L, is L infinite?

decideCFLinfinite(G: context-free grammar) =

1. Lexicographically enumerate all strings in * of length

greater than bn and less than or equal to bn+1 + bn.

2. If, for any such string w, decideCFL(L, w) returns True

then return True. L is infinite.

3. If, for all such strings w, decideCFL(L, w) returns False

then return False. L is not infinite.

Why these bounds?

Some Undecidable Questions about CFLs

● Is

L = *?

● Is

the complement of L context-free?

● Is

L regular?

● Is

L 1 = L 2?

● Is

L 1 L 2?

● Is

L1 L2 = ?

● Is

L inherently ambiguous?

● Is

G ambiguous?

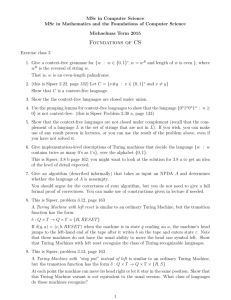

Regular and CF Languages

Regular Languages

Context-Free Languages

● regular exprs.

● or

● regular grammars

● = DFSMs

● recognize

● minimize FSMs

● context-free grammars

● closed under:

♦ concatenation

♦ union

♦ Kleene star

♦ complement

♦ intersection

● pumping theorem

● D = ND

● = NDPDAs

● parse

● try to find unambiguous grammars

● try to reduce nondeterminism in PDAs

● find efficient parsers

● closed under:

♦ concatenation

♦ union

♦ Kleene star

♦ intersection w/ reg. langs

● pumping theorem

● D ND

Languages and Machines

SD

D

Context-Free

Languages

Regular

Languages

reg exps

FSMs

cfgs

PDAs

unrestricted grammars

Turing Machines

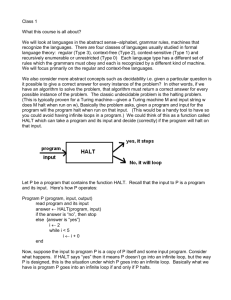

Grammars, SD Languages, and Turing Machines

L

Unrestricted

Grammar

SD Language

Accepts

Turing

Machine

Turing Machines

We want a new kind of automaton:

● powerful

enough to describe all computable things

unlike FSMs and PDAs.

● simple

enough that we can reason formally about it

like FSMs and PDAs,

unlike real computers.

Goal: Be able to prove things about what can and

cannot be computed.

Turing Machines

At each step, the machine must:

● choose its next state,

● write on the current square,

● move left or right.

and

A Formal Definition

A (deterministic) Turing machine M is (K, , , , s, H):

● K is a finite set of states;

● is the input alphabet, which does not contain q;

● is the tape alphabet,

which must contain q and have as a subset.

● s K is the initial state;

● H K is the set of halting states;

● is the transition function:

(K - H)

non-halting tape

state

char

to

K

state tape

char

{, }

direction to move

(R or L)

Notes on the Definition

1. The input tape is infinite in both directions.

2. is a function, not a relation. So this is a definition for

deterministic Turing machines.

3. must be defined for all (state, tape symbol) pairs unless the

state is a halting state.

4. Turing machines do not necessarily halt (unlike FSM's and

most PDAs). Why? To halt, they must enter a halting state.

Otherwise they loop.

5. Turing machines generate output, so they can compute

functions.

An Example

M takes as input a string in the language:

{aibj, 0 j i},

and adds b’s as required to make the number of b’s equal the number

of a’s.

The input to M will look like this:

The output should be:

The Details

K = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}, = {a, b}, = {a, b, q, $, #},

s = 1, H = {6}, =

Notes on Programming

The machine has a strong procedural feel, with one phase

coming after another.

There are common idioms, like scan left until you find a

blank

There are two common ways to scan back and forth

marking things off.

Often there is a final phase to fix up the output.

Even a very simple machine is a nuisance to write.

Halting

● A DFSM

M, on input w, is guaranteed to halt in |w| steps.

● A PDA M,

on input w, is not guaranteed to halt. To see

why, consider again M =

But there exists an algorithm to construct an equivalent PDA

M that is guaranteed to halt.

A TM M, on input w, is not guaranteed to halt. And there is no

algorithm to construct an equivalent TM that is guaranteed to halt.

Formalizing the Operation

A configuration of a Turing machine

M = (K, , , s, H) is an element of:

K ((- {q}) *) {}

state

up

to current

square

(* (- {q})) {}

current

square

after

current

square

Example Configurations

b

(1) (q, ab, b, b)

(2) (q, , q, aabb)

Initial configuration is (s, qw).

=

=

(q, abbb)

(q, qaabb)

Yields

(q1, w1) |-M (q2, w2) iff (q2, w2) is derivable, via , in one step.

For any TM M, let |-M* be the reflexive, transitive closure of |-M.

Configuration C1 yields configuration C2 if: C1 |-M* C2.

A path through M is a sequence of configurations C0, C1, …, Cn

for some n 0 such that C0 is the initial configuration and:

C0 |-M C1 |-M C2 |-M … |-M Cn.

A computation by M is a path that halts.

If a computation is of length n (has n steps), we write:

C0 |-Mn Cn

Exercise

A TM to recognize { wwR : w {a, b}* }.

If the input string is in the language, the

machine should halt with y as its current

tape symbol

If not, it should halt with n as its current

tape symbol.

The final symbols on the rest of the tape

may be anything.

TMs are complicated

• … and low-level!

• We need higher-level "abbreviations".

– Macros

– Subroutines

A Macro language for Turing Machines

(1) Define some basic machines

● Symbol

writing machines

For each x , define Mx, written just x, to be a machine

that writes x.

● Head

R:

L:

moving machines

for each x , (s, x) = (h, x, )

for each x , (s, x) = (h, x, )

● Machines

h,

n,

y,

that simply halt:

which simply halts (don't care whether it accepts).

which halts and rejects.

which halts and accepts.

Checking Inputs and Combining Machines

Next we need to describe how to:

● Check

the tape and branch based on what character

we see, and

● Combine the basic machines to form larger ones.

To do this, we need two forms:

● M1

● M1

M2

<condition>

M2

Turing Machines Macros Cont'd

Example:

>M1

a

M2

b

M3

● Start in the start state of M1.

● Compute until M1 reaches a halt state.

● Examine the tape and take the appropriate transition.

● Start in the start state of the next machine, etc.

● Halt if any component reaches a halt state and has no

place

to go.

● If any component fails to halt, then the entire machine may fail

to halt.

More macros

a

M1

M2

becomes

M1

M2

becomes

M1

M2

a, b

b

M1

all elems of

M2

or

M1 M2

Variables

M1

all elems of

M2

becomes

except a

M1

a, b

M1

x a

M2

M1

x a, b

M2

and x takes on the value of

the current square

M2

becomes

and x takes on the value of

the current square

M1

x=y

M2

if x = y then take the transition

e.g.,

> x q

Rx

if the current square is not blank, go right and copy it.

Blank/Non-blank Search Machines

Find the first blank square to

the right of the current square.

Rq

Find the first blank square to

the left of the current square.

Lq

Find the first nonblank square to

the right of the current square.

Rq

Find the first nonblank square to

the left of the current square

Lq

More Search Machines

La

Find the first occurrence of a to

the left of the current square.

Ra,b

Find the first occurrence of a or b

to the right of the current square.

La,b

a

b

M2

M1

Find the first occurrence of a or b

to the left of the current square,

then go to M1 if the detected

character is a; go to M2 if the

detected character is b.

Lxa,b

Find the first occurrence of a or b

to the left of the current square

and set x to the value found.

Lxa,bRx

Find the first occurrence of a or b

to the left of the current square,

set x to the value found, move one

square to the right, and write x (a or b).

An Example

Input:

Output:

qw w {1}*

qw3

Example:

q111qqqqqqqqqqqqqq

What does this machine do?