Supporting People with Intellectual Disability and Dementia

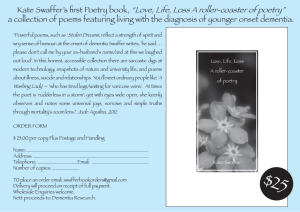

advertisement

Supporting People with Intellectual Disability and Dementia: A Training and Resource Guide Power Point Presentation for Direct Support Staff & Frontline Managers – Day Two Supporting people with Intellectual Disability and Dementia: A Training and Resource Guide Rachel Carling-Jenkins and Professor Christine Bigby Welcome Recap from Day One and review of worksheets Session 1 objectives Understand the prevalence of dementia within different populations of people with intellectual disability Understand what dementia means Understand how it is diagnosed Share your knowledge and stories Three elements common to all forms of dementia: 1. Progressive 2. Terminal 3. Incurable Session 2 objectives Understand what it is like to live with dementia by introducing the two laws of dementia Understand what it is like to live with dementia through “Supporting Derek” How can we effectively support and care for someone who has both an intellectual disability and dementia? Two Laws of Dementia Law 1 The Law of Disturbed Encoding: A person with dementia can no longer successfully transfer information from their short term memory into their long term memory Law 2 The Law of Roll-back Memory: As dementia progresses, long term memories will begin to deteriorate (roll back) and eventually disappear altogether A person with dementia lives in a different reality. Our job is to support and work with this alternate reality. Session 3 objectives • • • • Identify areas of practice which will need to change as you continue to work with someone with dementia Identify areas of practice which remain the same as you continue to work with someone with intellectual disability Understanding the changing needs of someone as they progress through the stages of dementia Understand behaviours within the context of dementia care Progression of dementia • Occurs at different rates • Abilities can change day to day or even within the same day • Not all factors present in all people • People can remain the same for long periods • Not all people will appear to go through all stages Three Stages: EARLY = MIDDLE = (Moderate) LATE = (Advanced) Changing balance of support and care Support Care Support Care Support Care Support Palliative Care Early to middle to late to terminal stages of dementia Session 4 objectives Understand the intersection of disability and aged care systems Role of mainstream health services in providing care to people with intellectual disability & dementia Role of mainstream allied health professionals in providing care to people with intellectual disability & dementia A collaborative effort is required – rarely will you find one expert who covers all areas Disability Services: expertise in intellectual disability Health Services: expertise in diagnosis and allied health support Aged Care: expertise in dementia care and service provision A little about my background… • Name? Position? • One thing that you want answered during this training? Agenda– Day Two 9.30 – 10.00 10.00 – 12.00 12.00 – 12.30 12.30 – 1.30 1.30 – 2.30 2.30 – 3.30 3.30 – 4.30 Reflections from Day One Session 5: General Strategies Session 6: Dementia-friendly environments Lunch Session 7: Responding to pain Session 8: Organisational responses Review & Evaluations By the end of the day… End of introduction Session 5 General Strategies Session 5 objectives Understand how to communicate with someone with disturbed encoding Understand the role of strategies in solving the puzzle of the past and the puzzle of the present Know how to bring meaning into everyday activity for people throughout different stages of dementia. COMMUNICATING WITH SOMEONE WITH DISTURBED ENCODING -SLOW -SIMPLE -SPECIFIC -SHOW -SMILE Slow Slow down your rate of speech Wait for the person to respond Take time to listen Be patient – completing conversations and tasks will take longer now Simple Present one idea or task at a time Use short, simple sentences or phrases Communicate in stages – e.g. First explain one step, then the next Reduce background noise – focus on one person at a time Specific Use names (Steve, Sue) not pronouns (he, she) Involve elements of reminiscence to every phase of your work by referring to specific people, things and/or events Show Point to objects Demonstrate how to do a task Cue someone in: e.g. ask someone to sweep the floor while holding a broom Use visual aids - photographs or choices: e.g. “would you like a cup of tea (holding the cup) or a juice (holding the juice container)?” Smiles Smiles communicate where words cannot Facial expressions can be used to express empathy and encouragement to someone who is becoming increasingly nonverbal Smiles are often returned, setting the mood for the day Don’t Ignore Don’t ignore expressions of feelings – remember they may be nonverbal expressions Don’t ignore identity as brother/sister, son/daughter, housemate, service consumer Don’t ignore their presence: don’t talk around a person like they are not there People with Dementia are entitled to be treated with dignity and respect We are all allowed to have bad days in our own home. MESSAGE Communication Strategies in Dementia for Care Staff Developed by: Helen Chenery, Erin Conway, Rosemary Baker and Anthony Angwin M – Maximise Attention E – Expression & Body Language S – Keep it Simple S – Support their Conversation A – Assist with Visual Aids G – Get their Message E – Encourage & Engage in Communication Puzzles of the past strategies The puzzle of the past Explore history to understand the present - Reminiscence support - Need to know a person’s background Knowledge of history can lead to: - Comfort in times of confusion or boredom - Understanding of “behaviours of concern” The puzzle of the past Explore history to understand the present • Reminiscence Support Strategies: - Life story work - Rummage box - Activity aprons Strategy: Life Story – Introduction (Name, including nick names) – Family history (including place in family, contact with family) – Childhood (including institutions lived in, schools attended) – Timeline of life – Significant events (such as holidays) – Significant places (which bring meaning to the person) – Significant people (including friends, influences) – Likes and dislikes – Favourite hobbies <Trainer to insert or show example here> Strategy: Rummage Box • Include reminders of happy events, hobbies, favourite clothes • Use reminders spanning different life stages Strategy: Activity Apron Provide sensory stimulation Can be used as an individual activity Provides links to the past and the present Also – activity pillows Sometimes called “Sensory Aprons” OTs can help with this. Group work Consider the following case studies: what kinds of reminiscence supports would you design for Ray or Jean? Now, think about the people you work with– do you know enough about their history to be able to design reminiscence supports for them? If not, where will you get this information? Case Study: Ray Ray used to live in an institution where it was his job to fold the laundry. Ray is a mad football supporter. He is never happier than when his team is playing. Ray loves Elvis. He’s even visited Graceland and he has photos to prove it! Ray delivers pamphlets in the neighbourhood. He has to fold them first, then walks around dropping them into letterboxes. Ray has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Discuss what Reminiscence supports you could design for Ray Case Study: Jean Jean has grown up with her family. Her sister’s children – all girls - have regularly come to stay with her and her Mum. Jean loved to feed them and help change them when they were babies. Jean worked in a workshop folding boxes for many years. One of the first symptoms of developing dementia occurred at work when her work became messy and disorganised. Jean loves to shop for clothes. She loves to accessorise with matching tops, jewellery and handbags. For birthdays, Jean would make people personalised cards. She could not write very well, but she would sign her name on the back of the cards. Discuss what Reminiscence supports you could design for Jean Researching history – a few ideas Ask family members who are still alive; Pick up cues from the person about their preferences (or ask them directly if in earlier stages) Check with members of staff, and organisational records Google: for information on institutions (e.g.. Kew Cottages History Project, online). The puzzle of the present – strategies The Puzzle of the Present A different reality: Does it really matter? • Prompt without frustration • Plan tasks and activities • Play along with reality and have fun Prompt Prompt without frustration - Visual prompts - Verbal prompts Does it really matter if you have answered the same question 10 times today? Prompts - Visual Visual Prompts • Prompts can be used to help people with dementia find their way around. They can also help people to understand where they are – e.g. I know I’m in the kitchen, because there is food on the bench. For example: • Create signs for toilet doors • Create a sign for bedroom doors • Use pictures of food on fridges and in the kitchen Prompts - Visual Examples of Signs Prompts - Visual Prompts - Visual Prompts – Verbal Verbal prompts • Gentle verbal prompting will help people with dementia orientate to their surroundings or refocus on tasks. Remember: - don’t get frustrated, you may need to prompt someone or answer the same question numerous times before seeing a result. Plan Plan tasks and activities: - Have a plan - Prepare all activities in advance - Avoid surprises - Explain your plan - Be flexible - Work as a team - Consistency Plan Good planning will enable people to maintain skills, maximise their independence, and avoid confusion. • Enable people to continue to make choices, but make them simpler. • Active Support– identify tasks which are difficult to perform and break them down. Can the person with dementia do some parts of the task? Play The role of staff • Celebrate what the person can do • Don’t ask questions • Don’t argue or contradict a person who is living in a different reality Ask yourself, does it really matter if the person with dementia believes their sister is coming to visit this afternoon? Group work Consider the second part of the case studies – of Ray and Jean. - How are you helping them make sense of the present? - What new strategies can you implement where you: Prompt without frustration Plan tasks and activities Play along with reality and have fun Case study – Ray, Part 2 Ray has been spending more time in his room lately. He doesn’t seem to be really doing anything while in there. Sometimes he will turn on the TV. Ray has not been participating in the pamphlet deliveries, leaving Barry to do most of the work himself. Barry has not complained, but other staff have started to tell Ray that he needs to “pull his own weight”. Ray looks upset and disappears into his room when you hear a staff member say this to him. Ray goes to a disco every two months. He has always enjoyed the dancing. The next one is Friday night and other staff are thinking of skipping it because Ray hasn’t realised it is on. Ray finds it difficult to get in and out of the bus now, so staying home seems reasonable. Last time Ray visited the psychiatrist he was diagnosed as being in middle stage Alzheimer’s disease. Case study – Jean, Part 2 Jean has been pulling out her clothes and laying them out on her bed during the day. It has become quite a task for staff to tidy up after her when it comes time for bed. Jean is enjoying the craft box you made for her. She gets it out at all times during the day and fiddles with the contents. Last night she got it out just before dinner. Jean had glue and glitter and cardboard all over the dining room table. Staff were unhappy and scolded Jean for making such a mess. They put her box away in the staff room where you find it when you come on shift the next morning. You read the diary and find that Sarah (a fellow resident) needs to go to the chemist today. You are on your own with Jean and Sarah, so both ladies will need to go. When you go look for Jean you find her laying clothes out on her bed. Adding meaningful activities into the day Are these examples of meaningful activities for someone with dementia? Why or Why Not? Think about the people with dementia you support. Are they engaged in meaningful activities throughout the day? Meaningful activity throughout the stages - Ray Early Stage – Ray folds the laundry most times Middle Stage – Ray rolls towels up in a ball and says they are folded Late Stage – Ray reaches out to touch the laundry basket when he is “wheeled” past but does not attempt to get clothes out of it Early Stage – Support Ray to fold the laundry, using active support – visual & verbal prompts Middle Stage – Continue to support Ray to fold the laundry, praising his efforts. Late Stage – Care for Ray by spending time with him. When Ray reaches out to the basket, stop. Spend time folding the clothes. Put clothes in Ray’s hands for him to hold while you work. Group work Now look at the case studies one last time. How will you add meaningful activity throughout the stages for Ray (e.g. paper delivery or Elvis/dancing) and for Jean (e.g. Craft or shopping/clothes)? When it comes to personal care… Individualised manual handling plan – updated regularly & proactively Procedures for providing personal care – consistently applied Regular staff meetings – to discuss strategies, changes and plans Tips for engaging with someone with dementia in personal care activities • Introduce yourself by name; • Get down on the person’s eye level; • Hold their hand; • Face the person when possible; • Do not rush; • Praise all efforts to help; • Use gentle touch to guide; • Help initiate activity; • Warm bathrooms and toilets (esp. in winter); • Use warm towels; • Maintain dignity; • Introduce water from toes up; • Know former preferences, e.g for bath/shower, for taste. Summary Support provided to understand the present Support provided to live within their reality Good quality of life for someone with dementia ? ? End of Session 5 – Quick break anyone? Session 6 Creating Dementia Friendly Environments Session objectives Understand what a dementia friendly environment looks like Understand your role in creating a dementia friendly environment What does a dementia friendly environment look like? A dementia friendly environment There are many things we can do within the home to assist people with dementia to make sense of their environment. Five Key Elements: 1. Calm 2. Predictable 3. Easy to interpret 4. Homely 5. Safe 1. Calm Calm versus Noisy and/or cluttered Calm: The role of staff - Remain calm Keep voices low and even toned De-clutter benches Do not show stress or frustration Don’t rush through activities Walk rather than run 2. Predictable Time for bed Know what to expect versus mixed messages Predictable: The role of staff - Pay attention to your body language, and the way you dress - Put the food on the table before calling someone to the dinner table 3. Easy to interpret Understandable versus Confusing Visuoperceptual difficulties can lead to • Spatial disorientation even in familiar environments; • Difficulty judging the height of floors when patterns or colours change; • Not wanting to walk on shiny tiles (they look wet and slippery); • Inability to locate items which are in front of them; • Distracted easily by patterns (in paintings or wallpaper); • Difficulty sitting in a chair, bed or toilet; • Restlessness in visually over-stimulating environments. (Reference: Alzheimer’s UK) Think about… - How to find the toilet without verbal prompt - How to find your bedroom by yourself - What clues are needed to show people what a room’s purpose is: such as the kitchen - Removing mirrors - The use of primary colours How do I wipe my hands? 4. Homely Homelike versus Workplace / clinical 5. Safe Safe versus Unsafe A few pointers… Outside the home: - No corners in paths - Ramps - Consistent colour patterns Inside the home: - Handles on cupboards - Consistent flooring - Primary colours to contrast doors - Avoid shadows and dim hallways - Remove locks on bathroom doors - Empty dishwashers promptly Safety devices Essential devices: Smoke alarms Safety switches First aid kit Fences around water (including pools and ponds) Security grills on upstairs windows Examples of additional devices to consider Hand rails Safety strips on stairs Automatic cut off devices Nightlights Sensor mats or door alarms High visibility (temporary)signage Power point protectors Case studies Group Work Consider the following case studies – what modifications would you introduce to the environment to “solve” the issues presenting? Case study: Pat Pat is a lady with Down syndrome and dementia. She is very overweight and needs to be encouraged to walk. One thing she likes to do is walk around the back yard. There is a ramp into the back yard and recently, Pat has needed coaxing to walk from the brown tiles in the kitchen out onto the red ramp. • Quick fix: one tin of paint! • Result: able to access the back yard again. Case study: Miles Miles is trying to make a cup of tea, but he’s getting frustrated when he can’t open the new cupboard doors. Staff have started making his cup of tea for him. Miles has stopped going into the kitchen. • Quick fix: put old handles back on doors • Result: Miles still able to open cupboard, still may need supervision – but maintaining some independence Case study: Ben Ben needs a new bed. Now that he has mobility problems associated with later stage dementia, Ben needs a hospitaltype bed which can be lowered as needed. The bed is smaller than his old bed and his favourite bed spread (Geelong Cats!) doesn’t fit. It gets caught in the mechanism, so it has been replaced with a plain navy blue cover. Ben stiffens up every time he sees the bed. Staff know that Ben had some bad experiences in hospital when he was younger. • Quick fix: Sew up the Cats bedspread to make it smaller; hospital backboard covered in left over material. • Result: Ben happy to go to bed at night Case study: Sue Sue is upset when agency staff or new casuals are on shift. They tend to be task orientated and concentrate on ticking off their job lists. Sue is in early stage dementia so she doesn’t need a lot of help with self care, but she has been craving more attention from staff over the last few weeks. • Quick fix: Clear guidelines left for new staff • Result: Sue gets the attention she deserves and new staff learn best practice principles Case study: Steve Steve has been wondering the hallways at night, raiding the fridge, then walking around knocking on bedroom doors. Staff have started locking the fridge at night and telling Steve to go back to bed. • Quick fix: staff gentle redirection, signs on his door, nightlight outside his door showing way back to his room, snack accessible on bright red plate on top shelf of fridge • Result: Steve gets up, eats his snack, goes back to bed often without prompting Summary Support provided to understand the present Support provided to live within their reality Dementia friendly environment created Good quality of life for someone with dementia ? End of Session 6 – Time for a lunch break Session 7 Responding to Pain Session objectives Understand the association between pain and dementia Recognise the signs of distress which may be indicating pain Know what to do when pain is present Pain in people with dementia Can no longer be reliant on verbal self report Pain is a common experience for people with dementia due to the associated physical conditions Often misinterpreted as ‘challenging behaviour’ Often left untreated Myths about pain #1: People with intellectual disability have a higher pain threshold when compared to the general population. Result: Pain in people with intellectual disability is ignored, left undiagnosed and untreated #2: Pain is an inevitable part of ageing Result: Pain in older people is ignored, leaving underlying treatable conditions undiagnosed and untreated Pain management is a Human Right The adequate provision of pain relief and pain management is a human right protected by the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in: Article 17 - Protecting the integrity of the person Article 25 - Health Pain in mid-late stages of Alzheimer’s disease In mid-late stages, plaques accumulate in the parietal lobe. Parietal lobe: responsible for structuring language & recognising sensory functions Result for person with AD - find it difficult to communicate pain - can no longer identify the type, location, duration &/or severity of pain experienced Pain in mid-late stages of Alzheimer’s disease Changes in “odd” or “challenging” behaviours are often attributed to the diagnosis of dementia. Symptoms of pain are being missed. If pain is left undiagnosed and/or untreated a person will experience: Increased intensity of pain; Increased duration of pain; As a result: Experience prolonged periods of associated distress; Escalation of ‘challenging’ behaviours; Decreased quality of life overall. Using behaviour to communicate pain People with dementia may communicate pain through the following behavioural signs: Decreased mobility; Change in mood; Sleep disturbance; Change in appetite; Prolonged periods of screaming or vocalisations. Group work Divide into two groups to discuss the following two case studies: Case Study 1: Sally Case Study 2: Ian Case study: Sally Sally was assessed as being in mid-stage Alzheimer’s disease. One day, she suddenly began to scream. Her throaty, loud vocalisations would continue for hours at a time. Staff complained that Sally could scream for their whole shift. Then sometimes, Sally would stop for no apparent reason. Everyone in the house was exhausted. Mary (one of Sally’s fellow residents) began to hit Sally and shout at her to be quiet. Staff were constantly having to keep Sally and Mary apart. Sometimes this meant taking Sally into the office with them, where she would scream while they were trying to make phone calls. One day, Sally suddenly stopped screaming. She sat in her chair, no longer feeding herself or interacting with anyone. Soon after she was assessed as having moved into the late stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Questions for Group Work: 1. What investigations could staff have carried out to identify the source of Sally’s screaming? 2. What quality of life did Sally have while she was screaming? 3. Why did Sally suddenly stop screaming? (Prompt: Was she no longer in pain?) Case study: Ian Ian was generally a happy man. He had never learnt to read or write, but loved to look at picture books. He’d help out around the house when he could. Now that he had developed Alzheimer’s disease he did not always set the table right anymore (putting out three spoons instead of a knife, fork and spoon at each place setting), and sometimes he took the clothes off the line before they were dry. Staff were kind and covered his mistakes – praising him for setting the table for example, and discreetly putting the clothes in the dryer when required. One day Ian did not get out of bed. He complained of a pain in his left leg. Staff were very concerned. An ambulance was called and Ian spent a day at the hospital having scans on his leg. There was no reason for him to feel pain in his leg however and he was sent home. Ian refused to walk on his leg, crying out whenever he was coaxed to stand. Staff eventually bought Ian a wheelchair. He never walked again. Questions for Group Work: 1. What additional investigations could staff have carried out to identify the source of Ian’s complaint about his leg? 2. Ian broke his left leg when he was 10. How is this information useful in understanding what may be going on for Ian? 3. What quality of life did Ian have now that he was in a wheelchair? 4. When Ian used the wheelchair, did he still experience pain? Tools for identifying pain Abbey Pain Scale • Quantifies pain • Originally designed for aged care residents with late stage dementia • No specific training required to administer • Quick to complete Reference: Abbey et al 2004 Tools for identifying pain DisDat “Distress may be hidden but it is never silent” • Qualitative tool • Best completed by someone who is familiar with the person with dementia • No specific training required to administer Reference: Regnard et al 2007 Algorithm for the assessment of pain in adults with intellectual disability & dementia When pain is identified or suspected Medical Assessment Team Work Allied Health Assessment Action: Medical Assessment • Medical assessment is key to identifying underlying causes; • The use of PRN medication needs to be clearly defined by a person’s GP or specialist. Eg. What signs of distress indicate the need for PRN? • Further tests may be required to rule out treatable conditions. Action: Allied Health • Is equipment being used correctly? (e.g. Roho cushions, adjustments to wheelchair positioning) • Is equipment adequate? (e.g. Chairs at correct height to support posture, mattresses which minimise pressure sores, etc). Check with physio or OT. • Get help with communication strategies. • Obtain a swallowing assessment (e.g. if distress occurs at meal times). Ask a speech pathologist. • Need help with non pharmacological strategies? Seek out a dementia specialist or OT. Action: Team Work • Hold regular team meetings; • Identify organisational response to monitoring and assessing pain; • Abide by medical instructions regarding pharmacological responses to pain; • Follow guidelines from allied health professionals; • Brainstorm strategies for non pharmacological pain relief. …pharmacological interventions for persistent pain are most effective when combined with non-pharmacological approaches… Gibson, 2006 Some useful non-pharmacological strategies • • • • • • • • • • • • • Activity aprons or rummage box; Music; Massage; Non pharmacological Aromatherapy; Gentle exercise; strategies can provide Visiting the toilet; relaxation – thus Lying down; alleviating pain – Pressure care; and/or distraction from Keeping up fluids; pain. Puzzles; Extra cushions; Feet up; Change of scenery (e.g. going outside). Group work • Reflect on your case study; • Look at the tools & the Algorithm; • Recall the strategies from Session 4; then answer the following: - Do you think Sally / Ian could have been assessed as experiencing pain or distress according to the tools? - Follow the algorithm through – what observations would you have made? - If Sally / Ian had been identified as being in pain, what action could you have taken? Summary End of session 7 Session 8 Organisational Responses Session objectives Understand the organisational responses post-diagnosis Understand the role of support workers within the decision making process Know how, when, and with whom to share a diagnosis of dementia Understand the complex nature of making decisions around transitions Many decisions need to be made post-diagnosis Individual decisions Best Interest of Person Practice decisions Organisational decisions Decision making – a collaborative approach Family Support Staff & Frontline managers Medical practitioners Aged Care staff Person with dementia as focus Management of organisation Community health staff House mates & friends An example of reality? Management decides on transitions Support Workers decide on practice Next of Kin decides on disclosure of diagnosis Unclear and separate decision making structure Need for decision making protocols prior to crisis • Professional decision making by staff - which staff when ? So Paul told me to more or less start to look for alternative accommodation because they couldn’t manage in the house, you know? She said he needs high-level care and she gave me the form and she said “I want you to go now and look at nursing homes.” • No sense of rights of family or person He said: “Do you think we should ask a solicitor?” but I don’t want to fight anybody, I just want to know what the rights are as far as the bureaucracy is concerned…I mean they can’t just say: “Look, he has to go this afternoon”, can they? • Absence process, family involvement or independent advocacy Often hurried at time of acute health crisis - which subsequently passes • Such things are critical in face of health improvements and sense of puzzlement by aged care staff – Why is he here? – We can’t provide the same level of care – Much higher staff resident ratios in group homes • Irreversible decisions once taken (Bigby, Bowers, Webber, 2010) Responsibilities of frontline staff Inform team leader/manager as soon as a diagnosis of dementia is confirmed Adapt practice and day to day support Inform team leader/manager of changes to the balance of support and care being provided Coordinate with other services involved in person’s life – health day programs, leisure Liaise with family to extent they wish Inform team leader/manager of any feedback or complaints from other organisations (such as Day Programs) and/or next of kin This will enable the management team to make informed decisions. Responsibilities of Operational Management Put clear decision making processes in place which provide family & friends with confidence and clarity, and which provide frontline staff with clear direction Make informed decisions based on reports from frontline staff, particularly regarding the changing balance between support and care strategies Consider accommodation options, including the feasibility of environmental modifications, in early stages. Transitions don’t need to happen early, but planning for them should. Decisions affecting the individual: Disclosing Diagnosis Decisions affecting the individual To tell or not to tell… Once someone is diagnosed with dementia, decisions need to be made about who to share this information with – and how. Consider the following groups: Decisions affecting the individual Telling someone they have dementia Consider: - Pros and cons for each individual - Due to the effects of roll back memory, a person is likely to forget their diagnosis Case Study: Marley Marley sits at the kitchen table. He’s gently hitting his head. He looks up, slightly confused, and says “something’s wrong with me”. He did the same thing yesterday. Yesterday he even asked if running away would help. Marley was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease a month ago. Should Marley be told that he has dementia? Telling peers Consider: - Not knowing can foster resentment - Knowing means peers can play a role in support if they choose to Case Study – Ethel Ethel has been very difficult lately. She used to be so compliant and helpful. Now she is constantly picking on Beth. You have had to separate Beth and Ethel on more than one occasion. Beth has always been a bit aggressive and you have caught her shoving Ethel when she thinks you aren’t looking. Ethel was recently diagnosed with dementia. Will disclosing this diagnosis to Beth help restore harmony within the home? Bottom line: A support worker cannot take on the responsibility of telling peers that someone has dementia without direct instruction from management and/or next of kin. Support workers can make recommendations The role of friends • Demonstrating the importance of supporting relationships for people with intellectual disability who develop dementia Tips for telling peers Plan a quiet time and place Plan who is going to share the information (e.g. You might want to bring in a social worker, or the team leader.) Plan who might need to be there to provide support to peers (e.g. Keyworker, parents) Explain in simple terms, using visual aids Explain what this means for them Allow time for processing the information Lead an open and frank discussion Allow peers to contribute ideas about how to support the person with dementia to remain a valued member of the household Telling family - Next of Kin must be formally notified as soon as a diagnosis has been confirmed - Next of Kin will need information and regular updates - Next of Kin decisions: • Who else to disclose this to within the family • Involvement in future planning Case Study – Jim Jim is in late stage dementia. He can no longer walk or feed himself. Staff have begun to make preparations for end stage care. A case manager has come in to help with this – and asks what wishes the family have expressed. The staff express their doubts that Jim’s dad even knows about the diagnosis. “He’s so hard to talk to, you can never get him on the phone” is offered as the excuse. It is the responsibility of management to inform next of kin. Telling service providers • Essential for ensuring decisions are made with the best interests of the person with dementia and intellectual disability in mind • Neglecting to do this may lead to inappropriate supports and the breakdown of placements Case Study – Adam When Adam was first placed in residential care, his diagnosis of dementia was not disclosed. Adam was placed in a home with large open spaces where a lot of activity was taking place all the time. Adam found this distressing and reacted negatively. Staff were confused about this and both residents and staff complained to management about his poor behaviour. Eventually the placement broke down completely and his parents were left to find another place for him. How could this have been avoided? Keep communication links open Case Study – Jules Jules was diagnosed with dementia three years ago. At the time, a case manager was called in to help support staff at his residence to make adjustments and preparations necessary. Three years later the same case manager was called in to work at a Day Program. She noticed Jules attended and she asked how he was going. Staff were concerned that he may be developing dementia, but were yet to raise their concerns with his house. Day Program Supported Accommodation Service Telling medical professionals • Essential for hospital admissions • Essential to ensure adequate monitoring through stages (e.g. with regular practitioners) Decisions affecting practice: Balancing support and care Tips for balancing support & care • Hold regular staff meetings • Aim to provide a consistent level of support & care among the staff group • Provide regular feedback to management, particularly when the balance changes • Communicate feedback from allied health and medical professionals clearly to all staff Decisions at the organisational level: Accommodation and placement options Organisational policy decisions Policies should be in place which proactively address the organisation’s response to a diagnosis of dementia. These policies will help to avoid crisis transitions and will provide clear guidelines to staff and families about what to expect. Three directions for organisations 1. Ageing in place (until…?) 2. In-place progression 3. Transition to generic aged care facility Deciding which direction to take involves a number of complex factors. Key points for people making this decision Whatever approach you adopt: • Avoid crisis transitions • Consider the best interests of the person with dementia • Make a considered decision • Start planning early Which approach should be adopted? Factors influencing management policy decisions: • Capacity within organisation: - size, diversity - human resources – staff skills, numbers - funding availability - physical fabric and layout of houses • Capacity outside of organisation: - availability of dementia specific care • Access to medical practitioners and allied health: - regular basis - on call basis Factors influencing for each individual - desires and preferences of person and family - starting point for increased needs Option 1: Age in place Positives Negatives • Preferred option for most people with a terminal illness • Familiar environment retained • Existing relationships maintained • Minimise stress of moving • If staff are untrained, inappropriate care/support • Need for increased staffing levels particularly at night – posing resource issues • Physical layout of the house may be inappropriate • Impact on other residents • May not be able to access essential services due to location Ageing in place until….? Requires clear propositions until resources, until choice, until not optimal care, until death Option 2: In place progression Positives Negatives • Opportunity to maintain relationships within organisation • Higher staffing ratios • (Should be a) better equipped house • Disability connection not lost • • • • • • • Often in a different suburb, leaving people disconnected from their peers Often initiates change in day activities Concern over ability to provide palliative care Often grouped with other people with disability and dementia or ‘behaviours’ or illnesses Capacity - vacancy management too much or insufficient space Impact over time of longer term residents May not have expected expertise Option 3: Aged Care Positive Negative • Staff are trained in palliative care, and pain management • Easy access to medical practitioners and allied health professionals on a regular basis • Thorough understanding of end stage dementia • May be closer to family • Loss of social connections to house mates and staff • Often in different suburb • May mean loss of day activities as well as home • Difficult social environment – not inclusive • Younger and stay longer than other residents • Equity issues – low to high support needs Key is for clear process - transparent and planned decision making not as a result of acute health incident or bed blocking issues What you can do to make transitions easier Pack reminiscence materials, such as rummage box and life story work Pack familiar items such as doona covers and posters Take time to introduce the person to their new surroundings – if planned early there should be no rush Make yourself available for staff at the new accommodation to ask questions during the transition period Maintain contact through visits, taking peers with you (if they choose to accompany you) Group work Reflect on your role as a support worker or frontline manager. How can you assist a person with intellectual disability and dementia to successfully: - Age in place? - Progress within the organisation? - Transition to an aged care facility? Bigger Picture Solutions - Government • Develop Policy Directions & Articulate Commitments • Aging in place where ever home is - if appropriate • Equitable access to health and specialist aged care services Implementation Strategies. – Acknowledge premature aging -remove age barriers to ACAS, CACP’s – Acknowledge as ‘special group within Aged Care legislation - e.g specialist wings in RAC- build expertise within –numbers too small for specialist accommodation – Establish specialist clinics to deal with complex health issues and diagnosis – Measures to make health system more accessible – liaison nurses, nurse practitioners to bridge gap – longer term allied health training – Potential of the NDIS - Funding Mechanism to take account of changed needs as age for those within the disability system – – Specialist consultancy back up to health/ aged care/ disability services. Mandate decision making processes and individualised planning • - Bigger Picture Solutions - Disability Service System •Develop Organisational Policies and Capacity for Aging •Articulate organisational approach and commitments What does aging in place mean in this organisation What models will it put in place Adopt a life course approach to aging – healthy life style, occupation, relationships across all ages and programs •Put on place planned organisational response – Build knowledge and expertise through staff recruitment, training, specialist positions cross programs/ organisations – Develop organisational capacity –supervisors and managers – Build health advocacy skills to leverage for health related resources, as a right – Develop mechanisms for individualised planning and decision making processes re transitions. – Education for people with disabilities about middle age and aging – Build circles of support and ensure external advocates involved in decisions – Seize rather than avoid responsibility at individual and organisational levels • And finally what outcomes are sought •Greater clarity about outcomes sought for people with dementia •A sense of security: attention to physical and psychological needs, to feel safe from pain or discomfort and receive competent sensitive care. •A sense of continuity: recognition of the individuals biography and connection with their past. •A sense of belonging: opportunities to maintain or develop meaningful relationships with family and friend and to be part of a chosen community or group. •A sense of purpose: opportunities to engage in purposeful activity, identify and pursue goals and exercise choice. •A sense of achievement: opportunities to meet meaningful goals and make a recognised and valued contribution •A sense of significance: to feel recognised and valued as a person of worth, that you matter as a person. (Nolan et al. 2001, p.175) Summary Many decisions need to be made for people with intellectual disability once they have been diagnosed with dementia. Individual decisions Support workers need to Support decisions of managers And families and will often be Called upon to assist in carrying Out the decisions Best Interest of Person Practice decisions Organisational decisions End of session 8 Recap & Resources Objectives of this training Dementia and its effects on a person with intellectual disability How to modify support to respond to changing needs, including strategies to enhance quality of life & tips on how to create a dementia friendly environment External resources available for additional support as required Organisational responses to supporting people with intellectual disability and dementia The reality of living with dementia Law 1 The Law of Disturbed Encoding Law 2 The Law of Roll-back Memory A person with dementia lives in a different reality. Our job is to support and work with this alternate reality. Modifying practice Dementia is a progressive disease. Providing support in this context involves changing the balance between support and care. Ultimately, someone in the end stages of dementia will require specialised palliative care. What is the difference between current disability support practices and dementia support and care? The balance between support and care shifts as a person moves between the stages of dementia Navigating the system(s) Providing the best care to someone with intellectual disability & dementia will involve access to expertise from three areas: Disability Services: expertise in intellectual disability Health Services: expertise in diagnosis and allied health support Aged Care: expertise in dementia care and service provision Strategies Decision making – a collaborative approach Family Support Staff & Frontline managers Medical practitioners Aged Care staff Person with dementia as focus Management of organisation Community health staff House mates & friends Resources for staff groups For more information Torr, J.; Rickards, L.; Iacono, T. & Winters, D. (2010). Down syndrome and Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer’s Australia and Down Syndrome Victoria. PDF available for dowload: http://cddh.monash.org/assets/dsadbooklet-final.pdf Download from www.cddh.monash.org Supporting Derek DVD Available from: http://www.jrf.org.uk/publications/s upporting-derek Recommended Spark of Life A Whole New World of Dementia Care http://www.dementiacareaustralia.com/ Reflection Reflection What is one thing you will take away from this training which will contribute to the quality of life for the people with disability and dementia you support? Any questions? Follow up available… <describe what follow up you can offer staff> Evaluations End