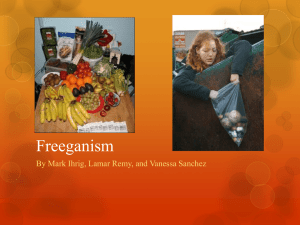

Waving the Banana At Capitalism

advertisement