Trademarks 101 & 102

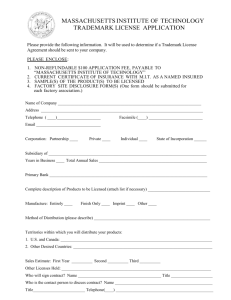

advertisement

WHAT IS A TRADEMARK? • A trademark is any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof, used in commerce to identify and distinguish the goods of one manufacturer or seller from those of another and to indicate the source of the goods. 15 U.S.C. § 1127. What makes a trademark eligible for protection? 1.) It must be in use in commerce; and a.) If a mark is not in use in commerce at the time the application for registration is filed, an applicant with a bona fide intent to use will be allowed to apply (application can be “reserved” for a short period of time, but no registration may occur until after the statement of use is filed. 2.) It must be distinctive. a.) This requirement addresses a mark’s capacity for identifying and distinguishing particular goods as coming from one producer or source and not another. • COMMON LAW RULES OF TRADEMARKS: • A trademark is anything that is: a.) Distinctive; b.) Nonfunctional; and c.) Used in Commerce WHAT DOES “USE IN COMMERCE” MEAN? • The Trademark Act now defines “use in commerce” as “the bona fide use of a mark in the ordinary course of trade, and not made merely to reserve a right in the mark.” • So what does that mean exactly? a.) The law in this area previously was largely unexplored, but has currently been a hot-button area for case law as of late. Sales made in a good faith effort to develop a business will likely be sufficient. 1.) Thus, it will likely be important to document efforts over time to develop the business in order to minimize any questions that may arise regarding first use in commerce. 2.) NOTE – This will not be true for service marks if the sales aren’t the actual rendering of services. PURPOSES OF TRADEMARK LAW • The primary purpose of trademark law is to prevent unfair competition by applying a test of consumer confusion and providing rights and remedies to the owner of the trademark. • The consumer confusion test is to assure that when buying a product or service bearing a particular trademark the product or service expected is actually delivered. • That means that trademark law is about protecting YOU, the consumer. WHAT IS “DISTINCTIVENESS?” • For word marks, courts split marks into 5 categories of varying distinctiveness: 1.) Generic Terms – These marks are not distinctive and cannot become distinctive. a.) Examples – Beer for beer 2.) Descriptive Terms – Some marks are not inherently distinctive and cannot be protected immediately, but can acquire distinctiveness over time. a.) Examples – Spray ‘N Wash for laundry soap 3.) Suggestive Terms – Some marks are inherently distinctive and therefore are protectable from the inception of their use. a.) Examples – Google for search engine results 4.) Arbitrary Terms -- Some marks are inherently distinctive and therefore are protectable from the inception of their use. a.) Examples – Apple for computers 5.) Fanciful Terms -- Some marks are inherently distinctive and therefore are protectable from the inception of their use. a.) Examples – Spanx for shapewear TIPS FOR DETERMINING “DISTINCTIVENESS” • The more a mark communicates about the associated goods and services, the less likely it is to be distinctive and the less useful it is as a mark. • Generic Terms – A claimed mark can become generic through: serving 1.) Genericide -- By becoming either the name of a product itself (as opposed to as a source identifier) or it has essentially become the name of a product itself through its permeation in the market (Aspirin became generic). Descriptive Terms – Describes the product. It is not inherently distinctive for trademark protection, but can become so through acquisition of secondary meaning. Descriptive terms are not automatically distinctive because others need to be able to compete fairly by describing their products using descriptive terms. 1.) Secondary Meaning/Acquired Distinctiveness – Consumers associate this descriptive mark exclusively with a brand/product. Suggestive Terms – Suggests in the minds of consumers something about the product (it does not explicitly say what the product is like a descriptive mark would do). They require an imaginative step. 1.) These marks are inherently distinctive and do not require acquisition of secondary meaning in order to receive trademark protection. • TIPS FOR DETERMINING “DISTINCTIVENESS” CONTINUED • Arbitrary Terms – A mark that has a definition, but the definition has nothing to do with the product sold. a.) These terms are inherently distinctive and do not require secondary meaning in order to receive trademark protection. b.) NOTE – Arbitrary terms should not be confused with misdescriptive marks, which are not registerable. • Fanciful Terms – An invented word to describe the product. a.) These terms are inherently distinctive and do not require secondary meaning in order to receive trademark protection. EXAMPLES OF TERMS THAT BECAME GENERIC E S C A LATO R ASPIRIN THERMOS GENERIC CONTINUED S HR E D D E D W HE AT ICE PAK EXAMPLES OF DESCRIPTIVENESS FISH-FRI SHARP DESCRIPTIVENESS CONTINUED BEST BUY FOOD FAIR EXAMPLES OF SUGGESTIVE MICROSOFT IVORY SOAP SUGGESTIVE CONTINUED CHICKEN OF THE SEA HULAHOOP EXAMPLES OF ARBITRARY APPLE COMET CLEANER ARBITRARY CONTINUED CAMEL D E LTA A I R L I N E S EXAMPLES OF FANCIFUL TRADEMARKS KODAK XEROX FANCIFUL CONTINUED REEBOK EXXON FILING BASIS FOR TRADEMARK REGISTRATION • You cannot register a mark with the USPTO without use in interstate commerce • States may have power to regulate marks not used in interstate commerce but that doesn’t grant federal registration rights. • State registration of marks does not put people on very good notice. • Willful notice is going to be hard to establish because most state registers are not open to the public. • State registration may get a smaller company territorial rights, but that may mean that national corporations can proceed with business anywhere else. • There are four different ways to file for Federal Trademark Registration • (1) Foreign Filings • (2) Madrid Protocol Filings • (3) Actual Use Application • (4) Bona fide Intent to Use Application • For US applicants, there are only two bases that matter: Actual Use and Intent to Use ACTUAL USE V. INTENT TO USE • Actual Use: the mark is currently in use. • Provide date that it was first used at all • Provide date that it was first used in interstate commerce • Must demonstrate use – upload specimen showing actual use of mark with multiple goods and services. • Bona fide Intent to Use: to be used within 6 months of filing, but can be extended out to approximately 3 years without leave of the director. • Need extraordinary circumstances to delay • You must pay a fee for each extension • Must do the substantive examination • Then proceed to publication still as an Intent to Use TM. CLAIMS OF TRADEMARK INFRINGEMENT • Two Kinds of Trademark Fair Use – Nominative and Descriptive • Fair Use – A fair use of a trademark occurs when the term is used in good faith for its primary, rather than secondary, meaning and no consumer confusion is likely to result. However this does not protect against dilution claims. - The term must be used only in its descriptive sense. • A nominative use occurs when use of a term is necessary for purposes of identifying the trademark owner’s product, not the user’s own product. - Only use as much of the mark as reasonably necessary to identify the producer. - Cannot suggest sponsorship by the producer. • Certain parodies of trademarks may be permissible if they are not too directly tied to commercial use. - People should have a 1st Amendment right to actual commentary. - Some courts use a “likelihood of confusion” analysis while others expressly balance 1st amendment considerations against the degree of likely confusion. dilution - There are dangers in claiming fair use for parody because doesn’t require confusion and, unlike copyright law, the fair use exception is not statutory. TRADEMARK INFRINGEMENT CONTINUED • A descriptive use permits use of the term descriptively to describe the user’s products or services, rather than as a trademark to indicate to the source of the products or services. • Example: Ocean Spray advertised the flavor of its cranberry juice as “sweettart,” the court concluded that the use was a descriptive fair use and hence did not violate Sunmark’s right in the mark SWEETART for candies. Sunmark, Inc. v. Ocean Spray Cranberries, Inc., 64 F.3d 1055 (7th Cir. 1995). • There are two prongs set forth in Section 33(b)(4) for descriptive fair use defense: • 1) a descriptiveness prong; and • Requires a showing that the mark was used only to describe the user’s goods and services, and was used otherwise than as a mark. • 2) a good faith prong. • Many courts have analzyed good faith for fair use pruposes by duplicating the “intent” factor from the likelihood of confusion analysis • Ask: Did the alleged fair user intend to trade off the goodwill of the trademark owner? International Stamp Art, Inc. v. United States Postal Service, 456 F.3d 1270 (11th Cir. 2006). WHAT IS A SERVICE MARK? • The Lanham Act defines a “service mark” as a term or other symbol used in connection with services. • A service mark, just as the name implies, identifies the name, logo, device or a combination of these to differentiate the service provided by one business to that of the others. A service mark also names the origin of the service. • The Lanham Act requires that a service mark “identify and distinguish” the services of one person from those of another, and “indicate the source of the services.” • Examples of businesses that use service marks are food, insurance, and transportation services. • An example of the difference between a service mark and a trademark is a restaurant. The restaurant provides food services to clients so it requires a service mark. EXAMPLE OF A SERVICE MARK WHAT IS TRADE DRESS? • Trade dress consists of all the various elements that are used to promote a product or service. For a product, trade dress may be the packaging, the attendant displays, and even the configuration of the product itself. For a service, it may be the decor or environment in which a service is provided • For trade dress to be considered inherently distinctive, one court has required that it “must be unusual and memorable, conceptually separable from the product, and likely to serve primarily as a designator of origin of the product.” • Functional aspects of trade dress cannot be protected under trademark law. For example, a company that claimed trade dress on a round beach towel lost their rights when the Seventh Circuit determined that the towel design was primarily functional (despite the fact that the trade dress had been registered and had achieved incontestable status). (Jay Franco & Sons, Inc. v. Franek, 615 F.3d 855 (7th Cir. 2010)). Only designs, shapes, or other aspects of the product that were created strictly to promote the product or service are protectable trade dress. TWO PESOS, INC. V. TACO CABANA, INC. • Taco Cabana owned and operated several restaurants in Texas with a particular theme. Several years later, Two Pesos opened up a chain of restaurants copying Taco Cabana’s restaurant style/theme. • Taco Cabana sued Two Pesos for trade dress infringement. • The jury in the District Court found that Taco Cabana’s trade dress was inherently distinctive, but had not acquired secondary meaning. Two Pesos appealed arguing that the trade dress needed secondary meaning in order to be inherently distinctive. • Issue – Is proof of secondary meaning required to protect the trade dress of a restaurant that is found to be inherently distinctive? • Holding – “If it is [inherently distinctive], it is capable of identifying products or services as coming from a specific source and secondary meaning is not required. This is the rule generally applicable to trademark, and the protection of trademarks and trade dress under § 43(a) serves the same statutory purpose of preventing deception and unfair competition. There is no persuasive reason to apply different analysis to the two” TACO CABANA: TWO PESOS: TACO CABANA: TWO PESOS: ARTISTIC RELEVANCE • The artistic relevance test is based upon the protections afforded artistic works under the First Amendment. • Rogers v. Grimaldi sets out the standard for the artistic relevance test. • A celebrity’s name may be used in the title of an artistic work so long as there is some artistic relevance. Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994, 997 (2nd Cir. 1989). • The Latham Act should be construed to apply to artistic works only where the public interest in avoiding consumer confusion outweighs the public interest in free expression. Rogers, 875 F.2d 994, 999. • You always have to weigh public interest in avoiding consumer confusion against public interest in free expression. ROGERS V. GRIMALDI • Issue -- Whether Rogers can prevent the use of the title "Ginger and Fred" for a fictional movie that only obliquely relates to Rogers and Astaire. • Procedural History – The District Court ruled in the defendant’s favor on summary judgment holding that “defendants' use of Rogers' first name in the title and screenplay of the film was an exercise of artistic expression rather than commercial speech.” • Appellate Court’s Holding – “Where a title with at least some artistic relevance to the work is not explicitly misleading as to the content of the work, it is not false advertising under the Lanham Act. This construction of the Lanham Act accommodates consumer and artistic interests. It insulates from restriction titles with at least minimal artistic relevance that are ambiguous or only implicitly misleading but leaves vulnerable to claims of deception titles that are explicitly misleading as to source or content, or that have no artistic relevance at all.” • “We hold that section 43(a) of the Lanham Act does not bar a minimally relevant use of a celebrity's name in the title of an artistic work where the title does not explicitly denote authorship, sponsorship, or endorsement by the celebrity or explicitly mislead as to content.” • Grimaldi Wins – Titling a film “Ginger and Fred” did not expressly mislead the public and was therefore permissible. ETW CORP. V. JIREH PUBL’G, INC. • ETW owns the rights to use Tiger Woods’ name and image in advertisements, etc. - The exclusive right to exploit his name, image, likeness, and signature, and all other publicity rights. Rush, the artist in issue, used Tiger Woods’ likeness in painting an image depicting the Master of Augusta tournament from 1997. While Tiger Woods’ name is not included in the actual painting, promotional material included Woods’ name and served as the alleged harm in this suit. The District Court granted summary judgment in favor of the artist. The artist’s use of Tiger Woods’ likeness represented a “fair use.” Using Woods’ name in promotional literature was considered fair use as it was merely descriptive of the goods to be sold. "Under the doctrine of 'fair use,' the holder of a trademark cannot prevent others from using the word that forms the trademark in its primary or descriptive sense.” "[A] trademark, unlike a copyright or patent, is not a 'right in gross' that enables a holder to enjoin all reproductions.” “We hold that, as a general rule, a person’s image or likeness cannot function as a trademark.” The artist wins again! LOOKING UP TRADEMARK REGISTRATION: • Visit the US Patent and Trademark Office’s website at: • For generalized searches, click on “Basic Word Mark Search.” • You can then search by trademark owner, name of the mark, and a whole variety of other things! TAYLOR SWIFT’S TRADEMARKS APPLICATIONS • “Party like it’s 1989” - 16 new applications pending review for all different goods and services. - All of them were filed under 1(b) intent to use. • “This sick beat” -16 new applications pending review for all different goods and services. - All of them were filed under 1(b) intent to use. • “Cause we never go out of style” - 3 new applications pending review • “Could show you incredible things” - 3 new applications pending review TAYLOR SWIFT’S TRADEMARKS CONTINUED • “Nice to meet you. Where you been?” - 3 new applications pending review • “Speak now” - 8 registered trademarks • “Fearless” - 3 abandoned after applications due to likelihood of confusion with Fearless Records • “Love, love, love” and “LOVE, LOVE, LOVE” - Both abandoned after applications • Once registered, these lyrics cannot appear without a license on anything from guitar straps to removable tattoos to paper plates (really anything Taylor Swift actually begins to use the marks with). KING.COM LIMITED • Creator of the game Candy Crush Saga • Attempted to register “Candy” - Many objected and the claim has now been abandoned. • Registered mark for “saga” THE THREE CATEGORIES OF TRADEMARK TROLLS 1. Those who register trademarks for names obviously belonging to a well known third party, with the clear intention of deploying those marks against the true owner. This is solved by showing priority in cancellation proceeding. 2. Those who register trademarks speculatively, do not use them, but look to deploy them against traders who later adopt the same name (a fraud without actual use). 3. Those who register trademarks and actually use them but seek to enforce the marks more widely than is legitimate (often against parties operating in different sectors).