Ecocriticism & Nature Poems

advertisement

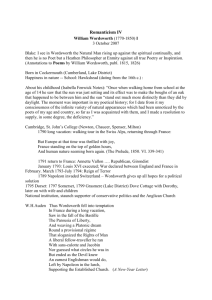

Ecocriticism & Some Romantic Poems Does Nature Exist beyond Human Languages? Outline • Different Usages of Nature • Ecocriticism: Starting Questions • Ecocriticism: – General Introduction; Methodologies; Issues; • Examples: – the picturesque and “Tinturn Abbey” – “Immortality Ode”: Nature & Childhood Romanticized? – “To Autumn”: Weather and Time • References Different Usages of Nature • Commodification: – “我愛大自然“ commercial; uses of signs of nature (e.g. picaresque landscape) in tea commercials and tourism promotion; Hinet “net the world” (with colorful animals in cage); “Fifteen-Dollar Eagle” • Symbolic/narrative Treatments: – – – – Romantic poems “Ode on Melancholy” –transience; 19th century landscape paintings Pre-Raphaelite poem “The Blessed Damozel” –3 lilies "Should Wizard Hit Mommy?" –the animals // father // daughter • Background images with symbolic meanings: – “La Belle Dame Sans Merci”; “Mariana”; “The Lady of Shalott”; “When I am Dead, My Dearest” “The Bourne” Different Usages of Nature (2) • ‘Realistic’ Description or hardship: – the painting Cabbage, melon and cucumber by Juan Cotán 1602, Dorothy Wordsworth’s journal; “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall” • ‘Natural’ Existence: – “A Slumber did my Spirit Seal” • From a Literal Journey to a Symbolic Quest: – “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud,” “Tinturn Abbey” – “The Blind Man” – 〈安卓珍妮〉; Surfacing; Into the Woods Different Usages of Nature (3): landscape and symbols Different Usages of Nature (4): frames and symbols Ecocriticism: Basic Definitions • Ecology (Cambridge Dic.): the relationships between the air, land, water, animals, plants, etc., usually of a particular area, or the scientific study of this. • Environmentalism: protecting the earth from human pollution and destruction. • Ecocriticism: Not just the studies of nature in literature; “ecocriticism has distinguished itself, debates notwithstanding, first by the ethical stand it takes, its commitment to the natural world as an important thing rather than simply as an object of thematic study, and, secondly, by its commitment to making connections ” (source). Ecocriticism: Starting Questions • Which of the above examples have ecological consciousness? • Which of the following is hurting the environment or the Earth? – meat eating; – wearing fake leather jacket, leather jacket, mink fur coat, amber earrings, leather boots, – overuse of plastic bags, paper bags and plastic packaging; • What does ‘to protect the Earth’ mean? What does ‘Nature’ or ‘the natural’ mean? Is anything ‘natural’ the best? • Derrida argues that there is nothing outside of text; but another philosopher Kate Soper warns, "it is not language which has a hole in the ozone layer.” Which do you agree with? Ecocriticism & Environmentalism • Damages we have done to the Earth: the degradation of soil, air and water, the loss of biodiversity, global warming, the depletion of the ozone layer, rising human population and consumption levels, • Exploitation: Consumption -- Eating animals; Production - subordinate humans, natural beings and the earth to commodity productions (Literature is not exempt from i Ecocriticism: General Introduction • Premise: Our embeddedness within an increasingly endangered earth. • Major claims: 1. Affirms nature writings (of Thoreau, Hawthorn, Romantic Poets & the contemporary ones): the ecocritics rigorously defend literature's capacity – to refer to a natural reality, – to realize the relations between landscape and lifestyle, and – to remind us of non-human perspectives (of animals, trees, rivers, mountains) towards an "environmental literacy". Ecocriticism: General Introduction (2) • Major claims: 2. To regain a sense of the inextricability of nature and culture, physis and techne, earth and artifact-consumption and destruction.“ Does ecology include Internet & the flows of capital? 3. Critique of Current Critical Schools as 'Cold War criticism' 'Global Warming criticism' – with their focus on human creativity, human agency and human social relations, – perpetuate that binary opposition of the human to the non-human, culture to nature. Ecocriticism: Methodologies 1. Critiquing the Canon 1. the Hebrew creation in Genesis I - "not only established a dualism of man and nature but also insisted that it is God's will that man exploit nature for his proper ends' (Lyn White Jr. 'The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis': 10). 2. classical tragedy -- reinforces the anthropocentric 'assumption that nature exist for the benefit of mankind,” 3. the pastoral tradition - a form of escapist fantasy, valorizing a tamed and idealized nature over wild no less than urban environments. Ecocriticism: Methodologies 2. Reframing the text – e.g. “The Blind Man” in the context of the natural world; 3. Revaluing Nature Writing –e.g. Alfred Leopold’s Sand Country Almanac; 4. Return to Romanticism’s “neopastoral”; 5. Reconnecting the social and the ecological e.g. Feminization of Nature; exploitation of the aborigines and their lands; 6. Regrounding (and reshaping) language. Issue I: culture and nature • • How is culture related to nature? (or City and Country?) Different definitions of culture – (Ref. Bate 3-5) 1. Cultivation – – – – Earliest definition (middle English to 18th century): ‘a cultivated field or piece of land’ Late middle English: from cultivated land to the action of cultivation; Early 17th century: extended to other forms of farming (of fish, oysters, bees, silk) 19th century: organic growth in the scientific sense (a culture of cholera germs) 2. Improvement of mind and manners by education and training, since early 16th century Issue I: culture and nature Different definitions of culture – In the 19th century, with the dimunition of the proportion of the population involved in tillage and the rapid growth of industrialization, the old sense died and the new one was further developed; 20th century: applied to the ‘aesthetic sphere.’ ‘refinement of mind, tastes, and manners’ => ‘artistic and intellectual side of human civilization’ culture vs. nature Issue II: the picturesque = aestheticization of nature • The problematic (Ref. Bate 136-) : “The picturesque was among the first artistic movements in history to throw out the Classical premise that art should imitate nature and to propose instead that nature should imitate art. It sought to treat entire landscapes in the manner in which earlier cultures designed gardens. . . . Garden landscaped park – ‘seemingly natural, but in fact highly artful.’ Issue II: the picturesque = aestheticization of nature • The word “landscape” –land-scape “land as shaped, as arranged, by a viewer. The point of view is that of the human observer, not the land itself.” (Bate 132) • “Environmentalism” – environ means ‘around’. Environmentalists are people who care about the world around us: anthropocentrism, the valuation of nature only in so far it radiates out from humankind, remains a given (Bate 138). deep ecology: “at the center of the deep ecological project is a critique of Cartesian dualism [of mind and matter, self and Other] and mastery.” How do we avoid being anthropocentric? Examples I: Wordsworth & the Picturesque • Bate draws upon Wordsworth as an exemplar of ecocritical thinking, for Wordsworth did not view nature in Enlightenment terms - as that which must be tamed, ordered, and utilised - but as an area to be inhabited and reflected upon. Parody of the Picturesque • Dr. Syntax • In Search of the PICturesque Parody of the Picturesque • Dr. Syntax In Search of the PICturesque The aesthete bemuses the locals The Picturesque • Gilpin’s “Northern Tour” No image. Harmoniously arranged cows Parody of the Picturesque • Dr. Syntax In Search of the PICturesque Not so harmoniously arranged cows, drawn ‘after nature’ A Parody of the Picturesque • The perils of the picturesque Wordsworth on the Picturesque • “He [another poet] used to go out with a pencil and a tablet, and note what struck him, thus: ‘an old tower,’ ‘a dashing stream,’ ‘a green slope,’ and make a picture out of it . . .But Nature does not allow an inventory to be made of her charms! He should have left his pencil behind, and gone forth in a meditative spirit; and, on a later day, he should have embodied in verse not all that he had noted, but what he best remembered of the scene, . . . “ (qtd in Bate 148) “Tinturn Abbey” • The picturesque “Tinturn Abbey” • Wordsworth’s omission of the abbey: to avoid the picturesque or to avoid the implied social relations of the landscape • Describes the interaction of nature and self (e.g. “Once again/Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs. . .”) • Self cliff; cottage larger landscape; • ll 94-102. “refuses to carve the world into object and subject; the same force animates both consciousness and ‘all things.’ Note: Romanticism from Different Perspectives • Deconstruction & Feminism - what Romanticism really valorizes is not nature/female, but the human/male imagination, human language and male quest; • New Historicism– the ideological function of romantic imagination and pastoral was to disguise the exploitative nature of contemporary social relations; • Bate – – Wordsworth repositioned in a tradition of environmental consciousness, according to which human well-being is understood to be coordinate with the ecological health of the land. (p. 162) Examples II: Nature & Childhood Romanticized? • Immortality Ode: Structure – • Stanzas I-II: past glory vs. his present sense of loss; • Stanzas III – IV: his confirmation of the present beings while missing the visionary gleam bespoken by a tree, a field and the pansy; • Stanzas V-VII – the process of human (our) growth and learning of different ‘arts,’ lies and imitation in the lap of ‘Earth’ • Stanza VIII – XI – reconfirmation of both past affections, recollections and truths and the present natural beings and child (child --we) Examples II: Nature & Childhood Romanticized? • Immortality Ode: • Do you agree that the child is father of the man? • How is nature presented in this poem? • How does Wordsworth resolve the issue of inevitable aging, forgetting and death? Examples III --“To Autumn”: Weather and Time • A New Critical Reading of the poem: as a simultaneous confirmation, prolonging of autumn’s sensual beauty and acknowledgement of its closeness to death. “ T O A U T U M N” Outline: 1. the sensual beauties of autumn in its very moments--early, mid and late autumn with their specific kinds of beauty. A. fruition B. storage C. music 2. Transience vs. prolonging the effects A. examples of transience + prolongment: 1. From “never cease” to last oozing, bloom the soft-dying day, stubble-plains, gnats 2. Actions gets smaller and smaller, but accumulated to show autumn’s richness B. effects prolonged by the mellifluous sounds and long vowels. C. Long sentences throughout the whole poem. (personification+ action, alliteration; sensual images ) “ TO A U T U M N” Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness, Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun; Conspiring with him how to load and bless With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run; To bend with apples the moss'd cottage-trees, And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core; To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells With a sweet kernel; to set budding more, And still more, later flowers for the bees, Until they think warm days will never cease, For Summer has o'er-brimm'd their clammy cells. Blue– images of death and disappearance “ TO A U T U M N” Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store? Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find Thee sitting careless on a granary floor, Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind; Or on a half-reap'd furrow sound asleep, Drows'd with the fume of poppies, while thy hook Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers: And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep Steady thy laden head across a brook; Or by a cyder-press, with patient look, Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours. “ TO A U T U M N” Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they? Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,-While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day, And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue; Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn Among the river sallows, borne aloft Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies; And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn; Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft; And gathering swallows twitter in the skies. Keats’ Life and world around the time of composing the poem, 1819 • Restoration of the monarchy in France in 1815. • His brother Tom's death in December, 1818 • Keats wrote a large amount of poems from 1819 to 1820; his second volume of poems appeared in July 1820. • Soon afterwards, by now very ill with tuberculosis, he set off with a friend to Italy, where he died the following February (1821). Other Views of “To Autumn” • “The whole point of Keats’ great and (politically) reactionary book was not to enlist poetry in the service of social and political causes. . .but to dissolve social and political conflicts in the mediations of art and beauty.(J. MacGann, 1985: 53) • “What Keats said to his readers—and his rulers—is comparable to what Galileo is reputed to have muttered after his forced recantation to the Inquisition: “And yet it moves.” (Hawthorn 1996: 176, 179) desperate confirmation of his belief in life and its contraries • A feminist reading of the presentation of autumn as a woman. Examples III --“To Autumn”: Weather and Time • (Bate 105) Air quality is of the highest importance for those whose lungs have been invaded by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Keats was hurried to death . . . by the weather. • Bad weather with humid fog in 1816-1818, but a beautiful autumn in 1819. cause –the eruption of Tambora volcano in Indonesia in 1815. The effect lasted for three years, straining the growth capacity of life across the planet.(Bate 97) Examples III --“To Autumn”: Weather and Time • A poem of networks, links, bonds and correspondences. Linguistically it achieves its most characteristic effects by making metaphors seem like metonymies. (e.g. mist and fruitfulness, bosom-friend and sun, load and bless – not naturally linked, but Keats makes the links seem natural.) • Also, syntactial, metrical and aural interlinking. • Human center? They are suspended, immobile. • The last stanza – at-homeness-with-all-livingthings References: • Websites: http://www.eng.fju.edu.tw/Literary_Criticis m/ecocriticism/ • ASAL Introduction to Ecocriticism: http://www.asle.umn.edu/archive/intro/intro .html • Bate, Johnathan. The Song of the Earth.