Bank_Swallow

advertisement

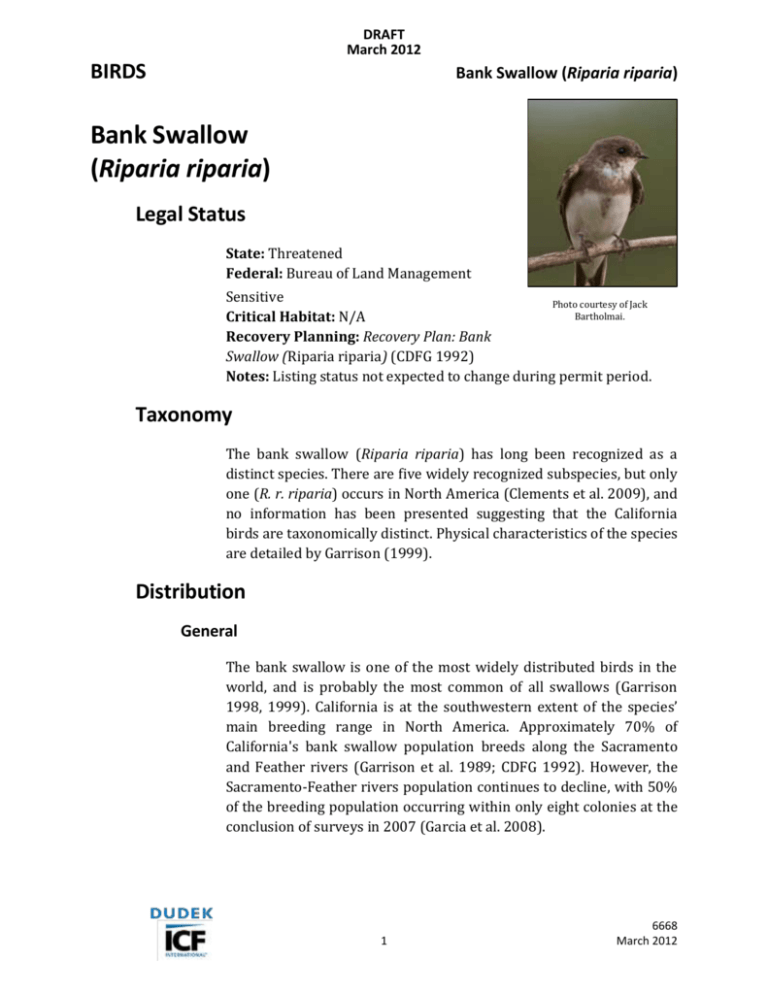

DRAFT March 2012 BIRDS Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Legal Status State: Threatened Federal: Bureau of Land Management Sensitive Photo courtesy of Jack Bartholmai. Critical Habitat: N/A Recovery Planning: Recovery Plan: Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) (CDFG 1992) Notes: Listing status not expected to change during permit period. Taxonomy The bank swallow (Riparia riparia) has long been recognized as a distinct species. There are five widely recognized subspecies, but only one (R. r. riparia) occurs in North America (Clements et al. 2009), and no information has been presented suggesting that the California birds are taxonomically distinct. Physical characteristics of the species are detailed by Garrison (1999). Distribution General The bank swallow is one of the most widely distributed birds in the world, and is probably the most common of all swallows (Garrison 1998, 1999). California is at the southwestern extent of the species’ main breeding range in North America. Approximately 70% of California's bank swallow population breeds along the Sacramento and Feather rivers (Garrison et al. 1989; CDFG 1992). However, the Sacramento-Feather rivers population continues to decline, with 50% of the breeding population occurring within only eight colonies at the conclusion of surveys in 2007 (Garcia et al. 2008). 1 6668 March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 BIRDS Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Distribution and Occurrences within the Plan Area Historical Early records of bank swallow in the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) Area are summarized by Grinnell and Miller (1944, p. 275). Records include a location near Big Pine on the Owens River in 1893 (the location is imprecise, but if in the Plan Area, it is at the northern edge) and a location at the southern end of the Salton Sea (no date given) in Imperial County. Grinnell and Miller (1944) add that there was no record of this species “from the southeastern deserts south of Owens Valley” except as noted above. More recent, but still historical occurrences (i.e., pre-1990), or occurrences with unknown observation date, are noted in Figure SPB3. These include a total of 13 records in the following areas: north of Hesperia, Edwards Air Force Base, east of Barstow along the Mojave River, and west of Barstow near the town of Lockhart, evidently in association with wetlands marginal to Harper Dry Lake (Dudek 2011). Recent There are 48 recent (i.e., since 1990) non-breeding bank swallow occurrence records in the Plan Area (Figure SP-B3) (Dudek 2011). Three of the recent locations are in the Barstow/Hesperia area and the other location is near the City of Ridgecrest, evidently in association with wastewater treatment ponds located north of the city. Recent occurrences include: south and east of the Salton Sea, north of Hesperia, Edwards Air Force Base, California City, the Baker area, along Interstate 15 east of Fort Irwin, and north of Ridgecrest, as well as several in the northern portion of the Plan Area in the Owens Lake area, near Independence, and at Tinemaha Reservoir (Figure SPB3). These occurrences are located near wetlands and open water that presumably provide suitable insect prey for food. There are no breeding records for the Plan Area. 2 6668 March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 BIRDS Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Natural History Habitat Requirements Breeding habitat for the bank swallow in California consists exclusively of vertical banks or bluffs with friable soils suitable for burrow excavation by the birds (CDFG 1992; Garrison 1998). The bluffs must be at least 1.0 meter (3 feet) in height to provide protection from predators. Garrison (1998) indicated that in various studies burrows are generally at least 1.0 meter (3 feet) above the base of the bank and 0.7 meter (2.3 feet) below the top of the bank, with burrows in the upper third of the bank. Nesting colonies in California have been observed to occur along banks with an average height of 3.3 meters (10.8 feet) (Humphrey and Garrison 1987, cited in Garrison 1998). The bank must be susceptible to erosion of sufficient intensity to maintain a near-vertical aspect with exposure of bare soils. Nesting colonies can vary greatly in size, ranging from 10 to several thousand burrows (CDFG 1992). Smaller colonies may be abandoned or relocated after a few years, which has contributed to considerable uncertainty regarding the species’ precise distribution in California (Garrison 1998; Garcia et al. 2008). Most colonies reported in California (e.g., by Garrison et al. 1989; CDFG 1992; Garrison 1998; Garcia et al. 2008) are associated with streams and thus with riparian vegetation types, and to a lesser degree, with lacustrine and coastal habitats (Green 1999). This is largely because flowing water is the most common agent of erosion that exposes and maintains the vertical profile of the bank or bluff. However, many nesting sites reported from outside California occur in road cuts or sand and gravel mines (Garrison 1998). Further, there are notable exceptions to the strong association of colonies with streams and riparian vegetation in California. Garrison (1989) reported colonies in extreme northeastern California that are located up to 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) from perennial water. Also, Moffatt et al. (2005) found high reoccupancy rates in colonies close to grassland habitat in the Sacramento-Feather rivers area. 3 6668 March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 BIRDS Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Foraging Requirements Bank swallows forage almost exclusively while in flight. Most insects taken by bank swallows are terrestrial and not dependent on surface water (Garrison 1989). Aerial foraging occurs over lakes, streams, meadows, fields, pastures, bogs, forests, and woodlands (CDFG 1992; Garrison 1998). During breeding, foraging generally occurs within 200 meters (656 feet) of the colony, but may sometimes occur at distances as great as 8 to 10 kilometers (5.0 to 6.2 miles) from the colony (Mead 1979 and Turner 1980, cited in Garrison 1998). Reproduction Bank swallows are normally colony nesters and are more colonial than other swallow species, with colonies having as many as 1,500 nesting pairs (Table 1) (Garrison 1998). The swallows excavate burrows that are typically 0.65 meter (2 feet) in length (range: 0.2 to 1.0 meter [0.7 to 3 feet]) in friable exposed banks of sand, gravel, or soil. Burrow entrances measured in California have been found to be approximately 5.5 centimeters (2.2 inches) in height and 7.2 centimeters (2.8 inches) in width (Garrison 1998). New burrows are typically excavated each year, but sometimes existing burrows are reused. Breeding X X X X Migration X X X X Other X X X X ________________ Notes: “Other,” Most bank swallows migrate to South America, but they occasionally overwinter in Southern California. Sources: Garrison 1999; Green 1999 Dec Nov Oct Sep Aug July June May April March Feb Jan Table 1. Key Seasonal Periods for Bank Swallow X Bank swallows are monogamous, although males often attempt extrapair copulation with fertile females. Pairing occurs either before or soon after the birds arrive at the colony site. Clutches of between 2 and 7 eggs are laid and are incubated primarily by the female. The 4 6668 March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 BIRDS Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) incubation period lasts approximately 14 days and is remarkably uniform across the range of the species (data presented by Garrison 1998). The young remain in the burrow for approximately 18 to 22 days before fledging. Within 10 days of fledging, juveniles are entirely independent and typically leave the breeding colony to join flocks of mixed juveniles and adults. These flocks usually forage in the general vicinity of the colony and roost for the night in trees or on river bars (Garrison 1998). Only one brood is raised per year (Garrison 1998). Spatial Behavior Bank swallows in California move at three spatial scales associated with migration, breeding, and non-breeding activity (Table 2). Bank swallows typically migrate in large flocks, often of several thousand birds, and that normally include other swallow species such as barn swallow (Hirundo rustica), cliff swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota), and tree swallow (Tachycineta bicolor) (Garrison 1999). Most birds migrate to and from widely dispersed locations between the extreme southern United States (a few birds overwinter in Southern California) and northern South America (Garrison 1999). Non-breeding movement is primarily observed among fledged juveniles and post-breeding adults during the time between fledging and migration. In California, this principally occurs during July and August. During this time, birds typically remain near the nesting colony but no longer use burrows, instead roosting at night in trees, on sand bars in rivers, or at other sites relatively safe from predators. Movements may occur up to several kilometers away from the colony just prior to migration (Garrison 1989, 1998, 1999). Movements by breeding pairs are largely confined to foraging within 200 meters (656 feet) of the colony. Courtship and mating behaviors immediately prior to breeding also occur at or very near the colony. Bank swallows are not territorial except in defense of the immediate burrow (Garrison 1998, 1999). 5 6668 March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 BIRDS Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Table 2. Spatial Movements by Bank Swallow Type Home Range Dispersal Migration Distance/Area Within 200 meters (656 feet) of colony Within a few kilometers of the colony 100 to 10,000 kilometers (62 to 6,214 miles) Location of Study California (Sacramento-Feather rivers colonies) Various Citation Garrison 1998 Various Garrison 1999 Garrison 1998, 1999 Ecological Relationships The principal ecological relationships relevant to bank swallows in the Plan Area concern their dependence on suitable banks and bluffs for nesting habitat, and on a sufficient supply of flying insects to provide forage. Garrison (1998) determined that nesting habitat for this species is essentially ephemeral: crumbling vertical banks of sand or soil are intrinsically short-lived habitats that tend to undergo substantial erosion at annual or more frequent intervals. As a result, bank swallows depend on access to a variety of potential colony sites within any given area, and may only use a fraction of the potential sites in any breeding season (40% to 60% of the available sites in the Sacramento River area, as estimated by Garrison [1998]). Bank swallows thus depend on the persistence of bank erosion processes. Based on work in the Sacramento River area, patch size is highly variable, with colonies occurring on banks ranging in length from 10 to 2,000 meters (33 to 6,562 feet) and in height from 0.5 to 20 meters (1.6 to 66 feet), with larger colonies occurring on larger patches and with a greater tendency for larger colonies than small to persist from year to year (Garrison 1998). Bank swallows are subject to predation of eggs and young by snakes, birds, and mammals that may enter burrows. Of these, snakes seem to be the principal predators. Fledged birds and adults are subject to predation by hawks and other birds (Garrison 1998). 6 6668 March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 BIRDS Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Population Status and Trends Global: Stable (NatureServe 2010) State: Vulnerable to imperiled Within Plan Area: Same as state The bank swallow was once considered a common species in California (CDFG 1992), but it has disappeared as a breeding bird in Southern California and has exhibited recent fluctuating population levels in central California (CDFG 2004). Studies in the 1980s and 1990s of several Sacramento River colonies, where the largest breeding populations occur (about 50% of the state total), estimated a high of 12,348 pairs in 1986 to a low of 7,525 pairs in 1991. In 1992, the number of pairs was estimated to be about 8,550 pairs (CDFG 1992). Recent analyses using both metapopulation models (Moffatt et al. 2005) and field surveys (Garcia et al. 2008) indicate ongoing decline of the Sacramento-Feather rivers population, which comprises over 70% of the statewide population. Threats and Environmental Stressors Breeding habitat loss due to riprap bank protection of natural stream banks is the main human-caused threat to the bank swallow in California (CDFG 2004; Garrison 1998; Garcia et al. 2008). Bank swallows, however, are relatively insensitive to moderate levels of human disturbance. Colonies occur, for instance, in road cuts and along banks beneath agricultural fields. However, bank undercutting due to boat wakes or fluctuating reservoir levels can cause collapse of banks used by colonies (Garrison 1998). Garrison (1998) also identified habitat fragmentation as a concern. Conservation and Management Activities Various conservation activities address the bank swallow in the Sacramento-Feather rivers area (Bank Swallow Technical Advisory Committee 2011). The state recovery plan for the species (CDFG 1992) notes that the overall goal of the plan is “the maintenance of a self-sustaining wild population.” The plan also notes that ongoing river bank protection projects represent the single greatest threat to 7 6668 March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 BIRDS Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) bank swallow populations in California. Consequently, the recovery plan identifies the following measures as necessary to maintain the continued viability of the species: Creation of artificial river banks Long-term protection, enhancement, and maintenance of natural habitat, particularly along the Sacramento River Development of set-back levees Impact avoidance Creation of habitat preserves. No ongoing conservation and management activities for bank swallow, or plans that include this species, have been identified in the Plan Area. Data Characterization The bank swallow is an exceptionally well-studied bird species at a local scale (e.g., Garcia et al. 2008; Garcia 2009). Studies of the species in California, especially since the 1970s, have focused almost exclusively on the main populations in the Sacramento-Feather rivers area. Very little is known about the distribution of the species elsewhere in California. Targeted studies would be needed to identify isolated nesting colonies. Such studies have either not been done or have not been done recently enough to provide a clear understanding of the species' distribution within the Plan Area. Management and Monitoring Considerations Garrison (1998) describes how efforts to create bank swallow habitat in California have failed, largely because the sites became eroded and vegetated after a very few years, and it would have required very high maintenance expenditures to avoid this outcome. It has become clear that management for bank swallows requires preserving and maintaining the geomorphic processes associated with creation of steep, non-vegetated, short-lived banks that create suitable sites for colonies, and maintaining such sites in sufficient density and proximity to allow frequent relocation of colonies. Within the Plan Area, it is also 8 6668 March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 BIRDS Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) reasonable to expect that management near suitable breeding habitat must maintain hydrological conditions conducive to wetland and riparian settings, which produce large numbers of flying insects. Predicted Species Distribution in Plan Area There are 1,053,575 acres of modeled suitable habitat in the Plan Area. Suitable habitat occurs in the High Desert Plains and Hills, Mojave Valley-Granite Mountains, Owens Valley, and Silurian ValleyDevil’s Playground ecoregion subsections from 1,300 to 4,300 feet. Suitable habitat includes areas near perennial streams and rivers, including the Mojave River and Owens River, perennial lakes and ponds, playas, swamps/marshes, freshwater emergent wetlands, and riverine wetlands. Modeled suitable habitat also includes areas with appropriate riparian vegetation, including Sonoran-Coloradan semidesert wash woodland scrub, Southwestern North American riparian, flooded and swamp forest/scrubland, and Southwestern North American introduced riparian scrub. Appendix C includes specific model parameters and a figure showing the modeled suitable habitat in the Plan Area. Literature Cited Bank Swallow Technical Advisory Committee. 2011. “Bank Swallow Portal.” Accessed April 22, 2011. http://www.sacramentoriver.org/ bankswallow/index.php. CDFG (California Department of Fish and Game). 1992. Recovery Plan: Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia). Nongame Bird and Mammal Section Report 93.02. Prepared by Nongame Bird and Mammal Wildlife Management Division. December 1992. CDFG. 2004. California Rare & Endangered Birds. Sacramento, California: CDFG. Clements, J.F., T.S. Schulenberg, M.J. Iliff, B.L. Sullivan, and C.L. Wood. 2009. The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World. Version 6.5. Edited by F. Gill and D. Donsker. Updated December 2010. http://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/downloadabl e-clements-checklist. 9 6668 March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 BIRDS Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Dudek. 2011. “Species Occurrences–Riparia riparia.” DRECP Species Occurrence Database. Updated November 2011. Garcia, D. 2009. “Spatial and Temporal Patterns of the Bank Swallow on the Sacramento River.” MS thesis; California State University, Chico. Garcia, D., R. Schlorff, and J. Silveira. 2008. "Bank Swallows on the Sacramento River, a 10-year Update on Populations and Conservation Status.” Central Valley Bird Club Bulletin 11(1):1–12. Garrison, B.A. 1989. Habitat Suitability Index Models: Bank Swallow. Sacramento, California: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Ecological Services. September. Garrison, B.A. 1998. “Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia).” In The Riparian Bird Conservation Plan: A Strategy for Reversing the Decline of Riparian-Associated Birds in California. California Partners in Flight. Accessed April 21, 2011. http://www.prbo.org/ calpif/htmldocs/species/riparian/bank_swallow_acct2.html. Garrison, B.A. 1999. "Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia).” The Birds of North America Online. Edited by A. Poole. Ithaca, New York: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Accessed April 25, 2011. http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/414/articles/ introduction. Garrison, B.A., R.W. Schlorff, J.M. Humphrey, S.A. Laymon, and F.J. Michny. 1989. “Population Trends and Management of the Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) on the Sacramento River, California.” In Proceedings of the California Riparian Systems Conference: Protection, Management, and Restoration for the 1990s. D. L. Abell (technical coordinator), 267–271. Berkeley, California: USDA, Forest Service, Pacific SW Forest and Range Experiment Station. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-110. Green, M. 1999. “Life History Account for the Bank Swallow.” Updated by CWHR Program Staff, September 1999. California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System, California Department of Fish and Game, California Interagency Wildlife Task Group. 10 6668 March 2012 DRAFT March 2012 BIRDS Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Accessed April 20, 2011. https://nrmsecure.dfg.ca.gov/ FileHandler.ashx?DocumentVersionID=17515. Grinnell, J., and A.H. Miller. 1944. The Distribution of the Birds of California. Pacific Coast Avifauna, no. 27. Berkeley, California: Cooper Ornithological Club. Moffatt, K.C., E.E. Crone, K.D. Holl, R.W. Schlorff, and B.A. Garrison. 2005. “Importance of Hydrologic and Landscape Heterogeneity for Restoring Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Colonies along the Sacramento River, California.” Restoration Ecology 13(2):391–402. NatureServe. 2010. “Riparia riparia.” NatureServe Explorer: An Online Encyclopedia of Life. Version 7.1. February 2, 2009. Data last updated August 2010. Accessed April 20, 2011. http://www.natureserve.org/explorer/servlet/ NatureServe?searchName=riparia+riparia. 11 6668 March 2012