New working conditions and new demands for childcare

advertisement

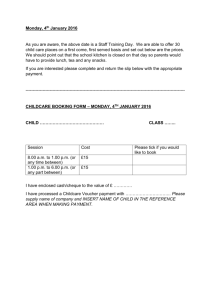

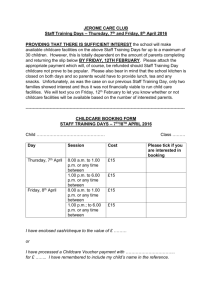

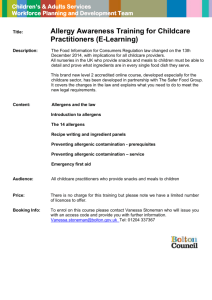

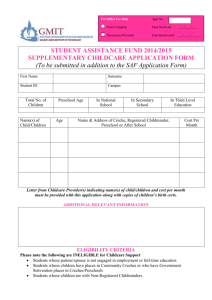

New working conditions and new demands for childcare: atypical working hours and vulnerability Claude Martin Research Professor at the CNRS Director of the Research unit on political action in Europe CNRS, Rennes Main objectives • Work and family life balance is a main issue in many European countries • This « conciliation » is even harder for parents concerned by atypical working timetables, and mainly in countries where no specific childcare solutions has developped • Our objective is threefold: – To identify different aspects of atypical times of work – To analyse the childcare needs of parents confronted to them – To present some experimental solutions developed in France to face these specific needs Structure of the presentation I. II. III. IV. The sample Impact of non standard working hours on every days’ life The care arrangements The subjective variables of the pressure I. The sample Three main variables • Family configuration: bi active couples and lone parents. • At least one children under 12 years old • Non standard working hours in 10 different sectors of activity. The common element is the staggered characteristic of these working hours (compared to the opening hours of childcare services and school). The interviewees worked at least 28h/week – Fragmented hours – Shift hours – Night hours – Early mornings and late evenings – Week end Most of the interviews have been made with women and some of them with both spouses. How can we define atypical times of work? • • • This notion refers to very different working conditions. The common point is that these hours are staggered which means not in phase with the standard hours of work, or with the normal opening of many public and private services variable or invariable hours – Louisia is a shopkeeper in a creperie. She works everyday from 5:00 to 13:00 and from 16:00 to 20:00. These hours are invariable, but staggered. – Eric is a sales representative; his hours are changing every day. • regular or irregular hours. – Laure is a nurse; her hours alternate from one week to another. She works on mornings (6:30 to 14:15) or on evenings (13:45 to 21:30). – Béatrice is a busdriver; her hours are always changing. «We have different time schedules each week. I work full-time. Some services correspond to 7h24 a day, others to 6h59 a day. It depends. This morning, I began at 6:28 and finished at 14:24 with a pause of one hour and 10, more or less (…) It changes all the time… Our timetables are never the same. Some weeks, our service is changing every day; some others, it is stable all the week. (…) You see, for example, it’s different, on the 21st, I finish at 15:30, the next day, I begin at 6:30, and then two days after I begin at 11:56 and stop at 20:30 and then I have a day off. » Table no. 3: Characteristics of the working hours of the persons met. Variable hours Regular Predictability + Léa (local police) Patricia (manufactur ing worker) Pierre (fireman) Laure (psychiatric nurse) 1 month 3 months All year long 1 month Predictability - Eric (sales representative vente) 3 weeks Invariable hours Irregular Mathilde (nurse) Béatrice (bus driver) Audrey (administra tive employee) All year long 6 weeks 1 month Anne (sales repreesentative) 1 week Louisia (shopkeeper) Séverine (cashier) Paul (cook) Sandrine (retail department supervisor) Fabienne (delivery agent) Jean (policeman) – many hitches Morgane (training for nurse assistant) – many hitches Main factors which impact on family life and parental responsibilities • Predictibility of the timetables – Mathilde, a nurse, explains about these variable and irregular hours of work: « It’s extremely complex… and even myself, I frequently feel lost even after 3 years in that job. I don’t catch my own planning. I can’t plan anything… I know what will be my planning during the current week; I know for the next week, because I will work three following evenings, but in 15 days, I can’t say anything. » • Negotiable hours – Bernard teaches at the university. He divorced and has the custody of two daughters half of the week. The flexibility of his times of work gives him the opportunity to group his teaching in the beginning ot the week and to care for his daughters the second part of the week. Atypical times of work for him doesn’t mean constraints, but choice and flexibility • The worth situation concerns families whose parents are working with variable, irregular, unnegotiable and unpredictable hours. II. Impact of non standard working hours on every day’s life 1. Hardness of non working hours 2. Impact on the care arrangement: unpredictability and negociability 1. Hardness of non standard working hours • The hardness of non standard working hours is a first element of pressure . – « I sleep when I can. This morning, I slept two hours and woke up for my young daughter. I slept again this afternoon. Some days I sleep only 5 hours, others 7h … but always in two times, because I have to wake up for my young daughter. » (Gabriel) – « What is really hard, is that if I start at 12 am, I’m not gone wake up at 5 am, I wake up at 7 or 7.15 to bring the children to school. And then, in the evening, at 9 pm, I don’t want to sleep, and I go to bed around 11h-11h30. And if I start early, I have to wake up very early, at 5 am, and I don’t want to get up. In fact, I always lack sleep ». (Patrick) • A staggered rythm – « It’s very difficult to rest. As I have only my sundays, I don’t have the impression to be on week end. I am always under pressure. I come back home on Saturday evenings, rather late and it’s difficult to rest. If we are invited at some friends, it’s very difficult to let go. I feel sleepy at 11 pm. And then sundays passes so fast! » 2. Predictability and negociability • The staggered characteristic of non standard hours is a main difficulty. Parents work when childcare services and schools are closed (after 6.30 pm in France and before 8 am) • The unpredictability of these working hours is a major difficulty for the parents who can not anticipate the organisation of the care arrangements • The difficulty to negociate these working hours is another problem. III. The care arrangements 3. 1. Formal care resources 2. Unformal care resources The stability of the care arrangements 1. Formal resources • The importance of childcare services in France: it is possible to have one’s child cared for from 8 am to 6.30 pm. • The lack of flexibility of formal services • The cost of flexible solutions – The ideal solution: an employee at home – But an expensive childcare solution • The development of innovative services 2. Informal resources • Shift parenting system: some couples of our sample manage to have different staggered hours of work. There is always one of the parents with the children. Non standard working hours can even be presented as positive. • The importance of the grand- parents: many families appeal to the grand-parents to care for the children. 3. The stability of the care arrangement • A variety of care arrangements combining formal and informal resources – Natacha and Gabriel: shift parenting – Elise, nursing auxiliary, lone parent, irregular and fragmented hours of work: the care arrangement is based on school facilities and her parents. • The importance of the stability of the care arrangement : – Mathilde and Claude: contract workers in the entertainment industry. – Béatrice: bus driver, lone parent. IV. The subjective variables of the pressure • • The satisfaction of the parents Two main subjective variables • To find the good balance 1. A care arrangement which is not always satisfactory • The case of Samantha and Christian: – Samantha is hair dresser and Christian works is employee in a pharmaceutical firm – Two daughters: 7 years old and 1 year old – Shift parenting • The grand parents’ solution – Elise is nursing auxiliary, lone parent. She has a 5 years old son. It is her parents who care for him after school. • 2. Two main subjective variable The conception of the role of parent and of family life – Some parents consider that collective child care is not a good solution, others that informal care (grand parents is not satisfactory) – A wish to spend as much time as possible with the children – The gender division of roles • Isabelle and Bertrand • Marie and Pierre • The investment in one’s professional life – Unsatisfaction at work: Mathilde – Satisfaction at work: Magali, Lucie and Laure 3. To find the good balance between work and family life: Christine and Gaetan • They are manager of a mini super market. • They have a 1 year and a half daughter. • Priority given to the time with their daughter and family time • The care arrangement: – Reduction of their hours of work – Recruitment of 3 employees to help them in the minimarket – Shift parenting – Family time on Sunday and Monday What does pressure mean? • • No direct (causal) links between constraints and pressure, or between non standard work schedules and feeling of time pressure There are objective variables like: – – – • Level of financial resources Level of informal resources (social network) Level of formal resources (offer of services) But also subjective variables (feelings and perception) Feeling of time pressure 1 • • • American literature gives some confirmation of our results USA : the 24/7 society with high level of employment flexibility (Presser, 2003) « In one fourth of dual-earner married couples and one third of those with children, at least one spouse works other than a fixed day shift… Almost half of dual-earner couples have at least one spouse who works weekends » Feeling of time pressure 2 • Some lessons of american research – Mattingly & Sayer (2006): more free time doesn’t mean less feeling of time pressure. • «the changing cultural context of work, leisure and parenthood all suggest that objective indicators of time use incrisingly decoupled from subjective feelings of time pressure ». • To explain this paradox, they refer to the evolution of the representations of parental role, to the model of « intensive mothering » and « involved fathering ». More and more parents consider that they are not enough involved in their caring and educational role. • There is also a gender aspect: female free time is often time for children, when male free time is personal • Third aspect, time pressure is not linked to the nature of the time (paid-work, leisure, care, household) but to the satisfaction linked to the activity Feeling of time pressure 3 • Roxburgh (2005) psychological distress is frequently higher for inactive or part-time female workers than for full-time employed women. – « Women who work full-time in the paid labor market may feel less stressed by parenting strains than their part-time or at home counterparts, because they have other roles that provide self-efficacy or give them a sense of relief from their anxieties about children » – These working women generally receive more support from their partner (which reduce pressure – Parenting role may be in itself a strong source of stress • Lemke & al (2000) underline the importance of the stability and quality of their care arrangement (formal and informal), which help to feel comfortable with one’s own parental and professional responsibilities Work satisfaction • • • • • • A main point concerns the ambivalence of the relation to working conditions (Baudelot & Gollac, 2006). The adequacy between work expectations and work achievement is a main factor of satisfaction and vice versa The importance seems to be: to find one’s own place in « l’espace social » Three different positions linked to social conditions and positions but not exclusively: investing, withdrawing and suffering This gives an individualist dimension (and not only a collective dimension) to this link between working conditions and satisfaction: factor of pressure or not One last point: This is different from Hakim’s position concerning choice and constraints, and her theory of preference. We don’t speak about preferences, but about the very variable impact of working conditions and constraints on each family configuration and personal feelings of pressure