How did Americans receive the Dred Scott decision?

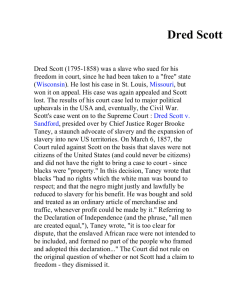

advertisement

How did Americans receive the Dred Scott decision? On the basis of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney's ruling in Scott v. Sandford in 1857, Senator Charles Sumner predicted that Taney's name would be "hooted down the page of history." A later chief justice, Charles Evans Hughes, acknowledged that Taney's ruling was in error but said that he was "a great chief justice." Because of his opinion, Taney, pictured above, remains one of the most controversial figures in American history. And the court's decision in the case, which is among some of its most important rulings, would come to symbolize the nation's racist past, the profound sectional divisions of the antebellum era, and what many believe to be the dangers posed by a court that acts beyond its mandate. The timing of the court's decision was important, as it came during a period of intense sectional divisions over slavery, which frequently ended in violence—most dramatically in Bleeding Kansas. At its core, though, the case was about Dred Scott, his wife, and children. Born into slavery around 1800, Scott lived in various regions of the country, including some free areas; it was his residence in the free state of Illinois and the free Wisconsin Territory that formed the basis of Scott's claim that he should be legally free. The final decision in the case was the culmination of a decade-long legal challenge marked by appeals and reversals, finally appearing before the country's highest court in 1857. The most brutal institution in American history, slavery existed in the United States from the early 17th century until 1865, when Congress enacted the Thirteenth Amendment shortly after the Union victory over the Confederacy in the Civil War. By that point, more than 4 million African American slaves lived in the United States. Although their communities thrived and multiplied, these people were subject to harsh living conditions and enjoyed none of the rights or freedoms so fiercely protected by white Americans. Many slaves fought back, in a variety of ways; Dred Scott was one slave who challenged his status in the courts, eventually becoming the plaintiff in one of the most important and infamous Supreme Court cases in U.S. history. In the first Perspective Essay, Professor Michael Green discusses the dramatic and divided reaction to the decision as it symbolized the deep fissures in the political culture of antebellum America, and particularly the virulence of sectional differences. Professor Nancy Stockdale suggests in the second Perspective Essay that abolitionists viewed the decision as a call to action, and thus it precipitated the Civil War. How did Americans receive the Dred Scott decision? Background Essay In the mid-1850s, the United States was deeply entangled in the politically charged struggle over slavery. The acquisition of land during the Mexican-American War and the passage of the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854) all contributed to ongoing tensions between the North and the South. Their debates on slavery were fierce, and they extended beyond the reaches of the states into the federal territories. In 1857, the historic Scott v. Sandford case (1857), better known as the Dred Scott case, rose to the U.S. Supreme Court. The case, which centered on a slave named Dred Scott and his quest for freedom, had important legal ramifications. It tested the legitimacy of past legislation prohibiting slavery, the application of due process, and the meaning of citizenship for African Americans. Finally, the case was one of the earliest examples of judicial activism, a theme that continues to resonate. The U.S. Supreme Court began hearing Scott v. Sandford (1857) in early 1856. While the Dred Scott case culminated in 1857, the case itself had a lengthy history drawn out for more than a decade. In its first phase starting in 1846, the legal case pivoted only on the effects that migration to a free state or territory had on a person's status as a slave. Born in Virginia around 1800, Dred Scott resided with the Peter Blow family, but in 1830, the family relocated to St. Louis and eventually sold Scott to U.S. Army surgeon John Emerson. During the next decade, as Emerson received new assignments, Scott accompanied him first to the free state of Illinois and later to free Wisconsin territory. Scott married a slave woman, Harriet Robinson, and they had two children. Eventually, in 1842, the Scotts returned with the Emerson family to St. Louis. The following year, Emerson died, and his widow contracted the Scotts out to neighboring families in need of slave labor. In 1846, Scott and his wife brought a case to the St. Louis circuit court, suing for their freedom. The initial case was thrown out on a technicality in 1847, prompting the Scotts again to bring legal action against Emerson. In 1850, the same St. Louis circuit court found for the Scotts, arguing that their shortterm residency in Illinois and the Wisconsin territory had effectively changed their status from slaves to free persons. Jubilation was not forthcoming, however, as Emerson immediately appealed the case and won it at the Missouri State Supreme Court. After securing new legal counsel, Scott appealed the case to the U.S. federal court in St. Louis. The case was renamed Scott v. Sandford since Emerson's brother John Sanford had become the defendant, although his name was erroneously spelled "Sandford." Sanford's attorney argued that because Scott was a slave, he was not a legal citizen of Missouri, and therefore he had no legal ground to bring such a lawsuit in that state. The federal judge sided with the defense once again, setting up a political showdown at the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court at the time of the Dred Scott case was nearly equally divided between Southerners (five justices) and Northerners (four justices). Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, who had served as attorney general under President Andrew Jackson, was appointed to the bench in 1836. From a family of aristocratic Maryland tobacco farmers, Taney supported the centralization of power advocated by the Federalist Party on nearly all issues, except slavery. On a personal level, he believed strongly in African American inferiority; nowhere would this viewpoint become more apparent than in the Dred Scott case. The other Southern judges included Peter V. Daniel of Virginia, James M. Wayne of Georgia, John Catron of Tennessee, and John A. Campbell of Alabama. Despite the sectional balance in the Court's makeup, the Southern justices maintained effective control. The Southerners represented an air-tight voting bloc, while the Northerners were less than solidified with one Whig, Massachusetts justice Benjamin R. Curtis; one Republican, Ohioan John McLean; and two Democrats, Samuel Nelson of New York and Pennsylvanian Robert C. Grier. In its decision, the Taney Court addressed three fundamental issues. Echoing the arguments raised at the federal circuit court, the Court explored the effects of residential mobility on slave status. Second, at the behest of Taney, the Court explored the constitutionality of federal legislation prohibiting slavery in federal territories. Because the question of African American citizenship was conspicuously absent from the U.S. Constitution, a battle over the framers' intentions also occurred. In a decisive blow to the antislavery abolition movement, two days after President James Buchanan's inauguration, the Court sided with Sandford in a 7–2 decision. The bloc of Southern judges was joined by Nelson and Grier, while Curtis and McLean were the lone dissenters. Chief Justice Taney issued the court's opinion, arguing for a limited interpretation of both due process and citizenship. He contended that legislation favoring the personal rights of slaves violated slave owners' right to due process under the Fifth Amendment. In straightforward prose, Taney wrote, "An act of Congress which deprives a citizen of the United States of his liberty or property, without due process of law, merely because he came himself or brought his property into a particular territory of the United States, and who had committed no offense against the laws, could hardly be dignified with the name of due process of law. . . . " The Missouri Compromise stripped slave owners of their lawful right to their property, argued Taney. Although a slave such as Scott might reside in free territory, his status still was controlled by his owner. In one fell swoop, Taney had undone officially the Missouri Compromise, which the Kansas-Nebraska Act theoretically already had done. In his opinion, Taney argued that African Americans "are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word 'citizens' in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States." Taney appeared to base his notions of African American citizenship on his own racial perceptions, declaring that the writers of the Constitution had considered them "a subordinate and inferior class of beings" possessing "no rights which the white man was bound to respect." From the chief justice's perspective, citizenship hinged on the notions of freedom, equality, and liberty. If such basic rights had not been extended, then one could not be considered a citizen of the United States. Moreover, in offering his justifications regarding race and citizenship, Taney attempted to downplay his own racial beliefs and instead laid the onus on the framers of the Constitution. He argued that they had never intended to extend constitutional protections to slaves. Consequently, there was no contradiction between the ideals advocated in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence and the fact that many of the framers actually had owned slaves. Scott's lawyer, Montgomery Blair, countered for the plaintiff, arguing that individual groups could be denied participation in such political functions as voting or jury duty without being denied full citizenship rights. Taney, however, contended that since the framers never intended for African slaves to be considered as anything other than property, it must follow that all persons of African descent are not citizens. What, then, explains the ample population of free African Americans in the North, queried Blair? Arguing for a narrow interpretation of federal citizenship, Taney replied that while free blacks in the North could indeed be considered citizens of a particular state, because they lacked the right of due process under the Fifth Amendment, they could never rightfully be considered citizens of the United States. The Dred Scott decision reignited the long-simmering sectional debate that would not be resolved until the Civil War. Clergy, congressional representatives, and citizens angrily debated the Court's actions. Furthermore, the Dred Scott case revealed the ambiguity of the U.S. Constitution. Only the passage in 1868 of the Fourteenth Amendment, extending citizenship to all races—notably African Americans— born in the United States, effectively ended the sort of convoluted argumentation put forth by Taney. Moreover, the case highlighted the judicial activism of the Taney court. Chief Justice Taney, although arguing many times over for the power of the federal government, abandoned his usual position in this case. Informed by his personal experiences with the institution of slavery and tinged by a conception of race held by many at the time, Taney's actions and that of his fellow justices demonstrated that the Court had moved away from its original role as arbiter of the law. They actively overturned congressional law, based not on a strict interpretation of the Constitution, but instead founded on their own political desires and prejudices. The Supreme Court of today, like its predecessor 150 years earlier, continues to grapple with this question of judicial activism and restraint. Perspective One - The Sectional and Political Divide While the U.S. Supreme Court has issued many controversial decisions, Scott v. Sandford may have prompted a more violent public reaction than any of the others. Announced on March 6, 1857, the ruling drew praise from its supporters, vehement denunciations from its opponents, and criticism from later historians and legal scholars who saw it as what future chief justice Charles Evans Hughes called one of the court's greatest "self-inflicted wounds." Dred Scott sued his master for his freedom, contending that he had been taken into states and federal territories that banned slavery. More than a decade passed between his lawsuit and the court's final ruling, and events—the Mexican-American War, Compromise of 1850, publication ofUncle Tom's Cabin, Kansas-Nebraska Act, birth of the Republican party, and violence in Kansas and against abolitionist U.S. Senator Charles Sumner—demonstrated that northerners and southerners alike had hardened in their views of slavery. Chief Justice Roger Taney hoped that his ruling would ease sectional tensions and resolve the debate. He could not have been more wrong. Rather than holding that, as a slave, Scott had no right to sue, or that, as property under the law, his move to free territory did nothing to change that status, Taney declared Scott a slave and the Missouri Compromise of 1820 unconstitutional. He claimed that African Americans had no rights as citizens, and Congress could not limit the spread of slavery. Six of the remaining justices concurred, with two dissenters—both northerners—blistering his majority opinion. The public response demonstrated the depths of the sectional and political divide. All sides viewed the opinion only through their perspective. Nor did they pull their punches: their comments were neither subtle nor impersonal. Consequently, their conclusions and predictions often proved wrong. Southerners and Northern Democrats who sympathized with them hailed the decision and its author. The Constitutionalist in Augusta, Georgia, said, "Southern opinion upon the subject of southern slavery … is now the supreme law of the land . . . and opposition to southern opinion upon this subject is now opposition to the Constitution, and morally treason against the Government." They hoped and believed the decision was the "funeral sermon of Black Republicanism," as Philadelphia's Pennsylvanian called it. One of the country's most popular newspapers, the Democratic New York Herald, said that the opinions "cover all the disturbing party and sectional issues upon the slavery controversy, and strike at the root of the mischief in every case." The Republican view was the opposite. The Chicago Daily Tribune left no doubt about how it saw the opinion in relation to the fight against slavery: "The teachings of the Gospel, the subtlest instincts of humanity and the desire of self-preservation throughout the North cannot be repressed in that way. Judicial injustice—always the resort of tyrants—has been met before. . . ." Horace Greeley's New York Tribune denounced the "wicked" decision for reducing the Constitution to "nothing better than the bulwark of inhumanity and oppression." William Henry Seward, a senator from New York whose allies and critics considered him radical on the issue, accused the majority of conspiring with President James Buchanan—which actually was true, though the evidence was not yet public. Taney found his comments so insulting that he later said if Seward had been elected president, he would have refused to administer the oath of office. Some Republican voices counseled and expected moderation. The New York Times, which tried to avoid becoming passionate about issues, predicted that the decision would "paralyze and astound the public mind." The Times noted that during the nullification crisis, South Carolina denied the supremacy of the federal government and the Supreme Court while northern states such as Massachusetts upheld it, but now their positions were "likely to be reversed . . . And this change of position illustrates the fact, to which it is due, that interest and not reason, rules over and regulates the action of States as well as individuals." The Times complained that the Dred Scott decision "completes the nationalization of Slavery," and predicted that while the public would accept the ruling, the decision would have the opposite effect that Taney intended: "it has laid the only solid foundation which has ever yet existed for an Abolition party; and it will do much to stimulate the growth, to build up the power and consolidate the action of such a party, than has been done by any other event since the Declaration of Independence." No one better exemplified the problem the decision created for moderate Democrats than Stephen Douglas. The senator from Illinois, twice a presidential candidate before the decision and still hoping to be elected, long had advocated popular sovereignty, which would allow territorial citizens to decide for themselves whether to allow slavery. Unfortunately for him, Taney had denied the legality of popular sovereignty. In his speeches and writings, and especially the next year in the debates during his reelection campaign against Abraham Lincoln, Douglas denied that the decision could stop Americans from reaching their own conclusions about slavery. His position cost him a great deal of the southern support he would need for his nomination and election—and helped provoke the split in the Democratic party in 1860 that helped Lincoln win the presidency. As Don Fehrenbacher wrote in his study of the case, "the literature of defense was less impressive in both volume and quality. This fact is not surprising, because the Court had put the ball in the antislavery court, so to speak, and the best defense for a decision allegedly complete and perfect was not further supportive argument but rather obeisance to the Court." In the end, the Civil War was the public response, and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments overturned Taney's corruption of constitutional law. Perspective Two - "This Devilish Decision" One of the most significant and controversial Supreme Court decisions of the 19th century, Scott v. Sandford (1857) continues to inspire historians of slavery, the Civil War, and the Antebellum United States to analyze its significance. Cited as a seminal turning point on the road toward Civil War, the Dred Scott decision fueled tremendous debate when it was announced by a Supreme Court divided 7–2. While supporters of slavery—and supporters of the notion that slaves were merely property rather than humans with inalienable rights—delighted in the decision, abolitionists were outraged. At the same time, many of the abolitionist movement’s most prominent thinkers viewed the Court's ruling as the spark their movement needed to inflame outrage against slavery's ills. Perhaps the most eloquent reaction to the Dred Scott case issued by an abolitionist came from the prominent former slave Frederick Douglass. A brilliant orator and writer who became internationally recognized as a leader of the American abolitionist movement, Douglass encapsulated both the fears and hopes of antislavery activists throughout the nation simultaneously in a speech on the decision, delivered soon after the Court rendered its verdict. Despite his lamentation of the Court's majority decision, which not only denied Dred Scott his freedom but also asserted that banning slavery in federal territories was unconstitutional and that slaves did not have protection under the Constitution, Douglass declared his belief that the decision would bring radical change to the nation: "You will readily ask me how I am affected by this devilish decision—this judicial incarnation of wolfishness? My answer is, and no thanks to the slaveholding wing of the Supreme Court, my hopes were never brighter than now. I have no fear that the National Conscience will be put to sleep by such an open, glaring, and scandalous tissue of lies as that decision is, and has been, over and over, shown to be." Not only did Douglass believe that American society was on the verge of recognizing that the "scandalous tissue of lies" issued by the Court was unjust, but he also declared it unconstitutional. He continued: "Neither in the preamble nor in the body of the Constitution is there a single mention of the term slave or slave holder, slave master or slave state, neither is there any reference to the color, or the physical peculiarities of any part of the people of the United States. Neither is there anything in the Constitution standing alone, which would imply the existence of slavery in this country. . . . Let me say, all I ask of the American people is, that they live up to the Constitution, adopt its principles, imbibe its spirit, and enforce its provisions." For abolitionists such as Douglass, the notion that African Americans could be denied the rights and responsibilities framed in the Constitution was nonsensical, given that the document itself did not explicitly discriminate in terms of race, religion, gender, or even in terms of "slave" and "free." Douglass's call on all Americans to thus live up to the ideals expressed in the very document that the Supreme Court claimed did not apply to slaves—simply because they were considered property, rather than American citizens—was a biting indictment of the patriotism of defenders of slavery as much as it was a brilliant legal analysis of the Constitution itself. Douglass was not alone in this opinion. Many abolitionists believed that an end to slavery was necessary for the United States to live up to its lofty Constitutional principals, a sentiment expressed in abolitionminded press editorials in the wake of the Scott v Sandford decision. One of the most direct came from the Evening Journal, a newspaper based in Albany, New York, a hotbed of abolitionist sentiment. The paper's editorial from March 9, 1857, called out to the American public thus: "All who love Republican institutions and who hate Aristocracy, compact yourselves together for the struggle which threatens your liberty and will test your manhood!" Not only was the newspaper horrified by the notion that the Supreme Court was claiming that slaves were not protected by the Constitution, but it viewed the Court as operating to protect the property interests of a fraction of the population—slaveholders in the South— rather than the majority of the American people. In both Douglass's speech and the editorial by the Evening Journal, historians may clearly see that abolitionists viewed the Dred Scott case with contempt. That is not surprising, given their cause. However, in both reactions, it is apparent that at least some abolitionists viewed the decision as a potential flashpoint for conflict between slave and free states, even if that meant armed struggle. On the eve of the Civil War, then, the Dred Scott case became notable for much more than simply one man's attempt to use the American judicial system to claim his freedom from servitude. Indeed, the Dred Scott case became a litmus test for the nation, asking Americans throughout the land if they were ready to free slaves and extend Constitutional rights to more people than ever before in the young nation's history. Conclusion In one of two dissenting opinions in the Dred Scott case, Associate Justice Benjamin Curtis argued that Congress indeed could legislate slavery in the territories, as it had done in over a dozen previous cases before the 1820 Missouri Compromise. Further, Curtis contended that Dred Scott's residence in free Illinois and Wisconsin had made him legally free. Shortly after the Dred Scott decision, Justice Curtis resigned from his position on the court. Kermit Hall, the leading scholar of the Supreme Court, concluded that Roger Taney's "inflammatory opinion," coming as it did "when forces were setting the stage for civil war . . . added enough fuel to the fire that it became unextinguishable." In the preceding Perspectives Essays, two scholars discussed the reception that this highly controversial opinion got from Americans at the time. In the first essay, Michael Green discussed the violent reaction that the decision provoked. Green highlighted the political and sectional divisions that the case underscored, particularly as seen in contemporary press accounts. In the second essay, Nancy Stockdale discussed the reaction of abolitionists including Frederick Douglass to the Dred Scott case.