File

advertisement

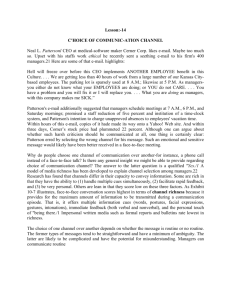

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Background of the Study Technology has revolutionized the school system today. Many classrooms are being retrofitted with “Smart boards” and computers. This is what they call the “21st Century” generation schools. Children now have access to computers and other electronic devices with all their virtual data stored electronically. It is already possible that for students to communicate to someone halfway around the world via instant messaging. Technology is another way to enhance traditional methods of teaching and learning but never replaces the human teacher inside the classroom. The technology available today has made a wealth of knowledge available to students anytime, anywhere and offers great potential for the speed and style of learning. Information is presented in so many ways that any type of learner whether gifted or disabled, can find the necessary materials online. This fact relates not only to the internet, but to all the many technological improvements in learning from smart boards to hand-held dictionaries and other soft wares available in many bookstores. With the increased access to information, there are however potential to teachers and students, and even parents as well. The information on the internet is there for all who have access without discrimination. People of all social strata are able to use technological advances, which is fairly new academic development in Philippines. 1 1 DEFINITION OF TERMS Computer – also called processor. An electronic device designed to accept data, perform prescribed mathematical and logical operations at high speed and display the results of these operations. Information Technology - often refers as IT. It focuses on the access of relevant information over a facility controlled by network of people. Information and Communications Technology also known as ICT refers to a tool where pupils or students use to facilitate teaching and learning emphasizing collaboration, innovation and cooperative learning among themselves regardless of space, time and distance. Internet – A means of connecting a computer to any other computer anywhere in the world via dedicated routers and servers. Learning - is defined as an act of change in behavior or performance as a consequence of experience. Teacher - is the most important variable in the learners’ education environment. He or she is regarded as the second parent of the pupils in school. Websites – is a depository of information destined for public or private use, usually residing in a remote server. When a computer terminal calls the website (using the HTTP or HTTPS protocol) the server responds by sending the information requested back to the user. Wi-Fi – is a mechanism for wirelessly connecting electronic devices. A device enabled with Wi-Fi such as a personal computer, video game console, smartphone, or digital audio player, can connect to the internet via wireless network access point. An access point (or Hotspot) has a range of about 20meters indoors and greater range outdoors 2 CHAPTER II REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE This chapter presents a review of foreign and local literature and studies on the effects of modern technology in teaching learning situation. Foreign Literature Modern Technologies With the advent of modern technologies today, “techies” can barely survive living in an archaic world without their electronic gadgets. Many years ago, we need to physically move from the couch over to the TV to change the channel. A time when there were few television networks, all of which were local by the way, would sign off by airing a taped recording of the Philippine flag proudly waving while a band played in the background. Today, we absolutely could not imagine living without modern technologies such as a cell phone, digital cable, the Internet, and microwave. The cell phone has got to be one of the most profitable and marketable portable pieces of technology available to us today. Everybody now owns very sleek model that allows multi-tasks and lots of applications installed for various needs of entertainment and information. Advantages and Disadvantages of Modern Technology Technology can be defined as science applied to practical purposes. Nowadays, when the rapidness of development and research is so impressive, it is easy to think about the advantages of modern technology. Nevertheless some people argue that science can destroy mankind. It is also obvious that we are close on an era where technology is limited only by our imagination. Therefore the most frequently asked question is: Does technology go the right way and will it save or ruin our civilization? 3 It can be argued that modern technology makes life easier and more dignified for most of people. The first and the major advantage is that medical science is very progressive and vastly available. Without the needed technology a lot of people would struggle with their health. In addition it saves many innocent lives. Technology in the classroom has advantages and disadvantages, too. Though it will serves as a tool to further the learning of the pupils and help the teacher teach the lesson, technology can be easily abused by relying too much on its use. There is tendency for pupils and teachers to depend so much on the capabilities of the gadgets rather that to exercise their resourcefulness and thinking abilities. Effects of Modern Technology In modern society, technology has brought us amazing surprises every day. Someone claims that modern technology is creating a single world culture. I completely disagree with this statement. I will list some of my reasons here. I believe that modern technology has improved multiculturalism and the communication between cultures. With modern communication technology such as TVs and phones, we can see what people at the other end of the world are doing, and with a modern airplane, we can travel to every corner of the world. This will greatly help us understand the cultural diversity of this world, and we will learn to appreciate the cultural difference of people from different part of the earth. Modern technology increases the communication between cultures. Eastern people can learn good virtual from western culture such as politeness and self-cultivation; and western people can also learn a great deal what determine managers' choice of communication media? Why do managers prefer to use one communication media over another? Within the domain of information system and communication research there exist substantial bodies of theories that explain manager's media choice. The purpose of this 4 chapter is to review the theories on media choice and to identify the deficiencies of these theories. EARLY RATIONAL THEORIES The early theories on media choice tend to be from the rational and individual school of thought. The first theory is the social presence theory of Short, Williams and Christie (1976). This theory emphasizes the psychological aspect of using communication media: media choice hinges upon the ability of the media to convey the nature of the relationship between the communicators. In this regard, communication media can be described as warm, personal, sensitive or sociable. A few years later, Daft and Wington (1979) proposed a language variety theory to explain media choice. It evolved from the idea that certain media, such as painting or music, are capable of conveying a broader range of ideas, meanings, emotions compared to mathematics. Such media have a higher language variety. This led to the suggestion that language variety needs to be matched with the communication task. Equivocal and complex social tasks are said to require a medium with high language variety. Obviously, this is not directly applicable to manager's choice as they do not use painting or music as a mean of communication, but this notion lays the foundation for media richness theory. This is where the discussion will turn to next. Modern Communication Technologies: Expanded Formulation The original criteria are based on the traditional mode of intra-organizational communication. In particular, it emphasizes the strength of face-to-face communication. By using face-to-face communication as a benchmark for comparison (Culnan and Markus, 1987), the presumption is that face-to-face 5 is the optimal means of communication. The fact that managers generally preferred to communicate face-to-face provides some support for this presumption. Relying on this presumption, a persistent view in the literature is that an electronic mode of communication is not a rich medium because it lacks the qualities that are deemed to be high in richness. Email, for example, is very low down the scale, because as a text based medium it has no social presence and has limited ability to transmit any cues. This in turn leads to the general claim that where managers perform equivocal tasks they would rely much less on modern communication media (e.g. Trevino et al, 1987; Daft et al, 1990). However, the original Daft and Lengel criteria were not design with modern communication media in mind. Indeed, in a study of interactive media, such as email, the notion of richness has been shown not to be an inherent property of the medium (Lee, 1994). Consequently, it is highly questionable that the notion of `richness', at least as based on the original criteria, can provide a fair basis of comparison between traditional and modern communication media. In seeing face-to-face as a de facto standard or an optimum media, the results are naturally biased against modern communication media. Modern communication technologies have qualities not found in traditional communication media. This leads some to argue that modern communication medium, such as email, is in fact much richer than was the case using the original criteria (Markus, 1994; Sproull, 1991). Sproull (1991) was the first to provide an updated definition of richness by incorporating the valueadded features of modern communication technologies, especially email and groupware. Subsequently, Valacich et al (1993) identified another related quality. The four addition criteria are outlined in Table 2.3. 6 Anyhow, it can be argued that the focus of media richness theory is still on face-to-face. In fact, it is to be doubted whether "richness" is an appropriate notion to assess modern communication technologies. The notion of richness just does not seem to cover the qualities possessed by modern communication technologies; these qualities go beyond `richness' and the notion of communication task equivocality. MEDIA RICHNESS THEORY: AN EVALUATION Empirical Evidence The researches papers studying media richness are summarized in There are numerous studies providing empirical support for media richness theory. The primary claim of the theory that managers will choose rich media (as defined 7 under the original criteria) in situation where the communication task is high in ambiguity has been established in many studies (Daft et al, 1987; Russ et al, 1990; Trevino et al, 1990; and Whitfield et al, 1996). Complementing such survey style studies is an investigation by Trevino et al (1987) in which the managers are interviewed as to the incidents and rationale for choosing particular communication media. The responses are overwhelmingly that fact-to-face communication (a rich medium) is preferred in situations where the messages to be conveyed are ambiguous. Adequacy Questioned by Modern Communication Technologies While there is a solid body of research supporting the position of media richness theory, an equally large number of research studies provide confounding evidence. Indeed, empirical support for media richness theory is particularly weak in relation to modern communication media like email or voice-mail (Markus, 1994; Markus et al, 1992; Rice and Shook, 1990). It is no surprise that research giving conflicting evidence tends to be of more recent origin. With the incorporation of more modern communication technologies in the research design, studies are only recently in a position to expose the predisposition of the media richness theory towards traditional communication media. The increased prevalence of technology usage in organizations in general may provide another explanation. In a Meta study by Rice and Shook (1990), the prediction of media richness theory was found not to hold. The inadequacy of the theory really became apparent in a study on email usage by Markus (1994). Markus (1994) conducted a fairly comprehensive study involving a survey of 504 managers and an interview with 29 personnel (whose positions range from chairman to administrative assistant), and collection of archival data. The study found 8 that managers do not regard email to be particularly rich. This is consistent with the richness model under the original criteria, but is inconsistent with the updated criteria. Yet the most curious finding is that mangers used email substantially more than the theory predicted. This study effectively weakens the media richness theory: the theory was not found to provide an adequate explanation and the updated criteria were also found to be incapable of capturing managers' perception of richness. Why? Using evidence from the interviews, Markus concluded that social processes provide a superior explanation of media choice. And this position is consistent with other studies: Schmitz and Fulk (1991), Schmitz (1987) and Steinfield and Fulk (1986).[9] Likewise, D'Ambra (1995) demonstrated media richness theory failed to fully explain media choice in an Australian study focusing on the use of voice mail in organizations. Reliability of Underlying Construct and Approach The reliability and validity of two fundamental constructs of media richness theory are still not clear. While there are plenty of papers examining the predictive and explanatory power of the media richness theory, and there are solid empirical justifications for the link between equivocality and media richness (Daft et al, 1987; Trevino et al, 1987; and Russ et al, 1990); the underlying construct of media richness and task equivocality have received limited attention in the literature. Only recently did a paper by D'Ambra (1995) investigate this issue. In most studies media richness is not something that is explicitly measured. This can be seen in the summary in Table 2.4. Often, it is simply determined by its position on the continuum of richness derived from the set of original criteria noted above. In other words, media richness is treated as an "invariant objective features" of each communication media (Schmitz and 9 Fulk, 1991).The central problem is that these original criteria are themselves outdated with no recognition of the very different qualities of modern communication technologies. After investigating the matter D'Ambra (1995) came to the conclusion that the reliability of the media richness scale is much weaker at the "lean" end of the scale. And at this lean end, of course, are found the modern communication technologies. D'Ambra claimed that this highlights the inability of the traditional media richness scale to capture the full range of attributes or qualities of these modern communication media. Again, the verdict is very similar in relation to task equivocality. In most prior studies equivocality is either not explicitly measured, or if it is, it is determined by a panel of judges and not by the subjects of the media choice research. Moreover, although the scales used was found to be "adequate", D'Ambra (1995) noted that its operationalization is "problematic". This is not surprising because a cursory examination of the literature on task equivocality and uncertainty reveals that although this construct has a long theoretical history and is well theorized conceptually, its operationalization is through the imperfect proxy of task uncertainty. Missing Task Characteristics Under media richness theory task characteristics refer primarily to the notion of equivocality. The question that arises is why just equivocality? A communication task can possess many other task characteristics. For example, the task could involve different locations, or there may be a time limit, or it may involve more than one person, etc. These other task characteristics are further considered. Failure to consider these task characteristics makes prior studies of media choice highly artificial. While the narrow perspective seems to serve its 10 purpose within the context of media richness theory, it is inadequate to provide an understanding of the overall media choice process. Indeed, as established subsequently in this thesis, equivocality alone is inadequate to explain the media choice process. This narrow focus also tends to be biased against modern communication media. This could explain some of the curious and conflicting results in prior studies. Local Literature “Teachers will not be replaced by computers but those who cannot use computers will be replaced with those who can” is a famous line nowadays. While it is quite obvious that teachers will not be fired due to its inability to become accustomed to the emergence of technology, various researches show that ICT has the power to increase motivation and learner engagement and help to develop life-long learning skills. This claim is also true and a mandate in the article XIV section 10 of the 1987 Philippine constitution stating that technology is essential for national development and progress. It was mentioned in the DepEd’s ICT4E strategic plan how the Philippine government embarked into various ambitious ICT integrated projects. Some are the DepEd 10-year modernization Program (1996-2005) dubbed as the School of the Future. Private sectors and different media outfits contributed also to this noble dream of integrating ICT in educating our children. Recently, Education and Communication Technology for Education (ICT4E) and DepEd Computerization Program (DCP) are already being felt in the classrooms. Among the subjects that best benefit from these programs is mathematics and as our means of sharing this success, the following objectives had been proposed and are intended to help in the ICT Integration enhancement of each 11 participating group or individual. These objectives will also be the focus of the group’s training/convention. To develop awareness on the DepEd ICT4E Vision and Strategic Plan; To develop skill in the use of ICT available package (ICT4E Classroom Model); To demonstrate the use of ICT in teaching mathematics; and To produce digital lesson plans for teachers ‘consumption. On top of the above objectives is the vision of ICT4E that says “21st Century education for all Filipinos, anytime, anywhere” this leads to transformation of students into dynamic life-long learners and valuescentered, productive and responsible citizens. Also, the goal of the DepEd’s ICT4E is to transform learners to be proficient, adaptable life-long learner where ICT plays a major role in creating a new and improved model of teaching and learning where education happens anytime, anywhere. To make this goal possible, the following strategic plans have to be done. Provide a threshold level hardware for schools Provide training for teachers Provide any necessary infrastructure Encourage schools to device their own ICT plans 12 CHAPTER III METHODOLOGY The Assessment Cycle Developing Assessment Questions The first part of the assessment cycle defines what you want to know: assessment questions, outcomes, and objectives. Because poor questions result in weak answers, it is critical to understand the purpose of an assessment and develop well-focused questions. Assessment and Evaluation It is easy to confuse assessment and evaluation because they are not distinct categories but rather a continuum. The first step in developing assessment questions is determining where your question falls along the continuum. “[Evaluation is] a broader concept than assessment as it deals with all aspects of a program including resources, staffing, organization, operations, and efficiency.”8 In general, evaluation consists of systematic investigation of the merit, worth, or significance of an object, a program, or a process.9 there are many types of evaluation, including, but not limited to: • Program evaluation • Needs assessment • Process evaluation • Cost-benefit analysis The difference between assessment and evaluation is important when discussing technology issues. To distinguish between assessment and evaluation, consider the questions’ focus. Questions about technology often 13 revolve around cost-benefit analyses, staffing, support, and infrastructure (types of and support for hardware and software). Many institutions have investigated infrastructure, what students want, what faculty feel they need, and satisfaction with technology support. These questions • Develop/refine the assessment question, outcome, objective. • Define assessment methods that will gather evidence. • Implement assessment methods, gather evidence, analyze data. • Interpret the results in terms of the assessment outcome, or objective. • Make decisions based on results and interpretations. Defining What You Want to Assess is concerned with evaluation. In contrast, assessment focuses on the effect of technology on student learning. If environment, technology, curricular and co-curricular activities, instruction, and student variables are part of the question, and if the focus is student learning, then this is assessment. Evaluation Questions •How does technology influence faculty workload? Does technology improve use of class time? Does technology require more preparation time? •Are students satisfied with technology support? •Can future demand for technology be predicted? How many technology-enriched classrooms will be needed in the next five years? •What barriers do faculties think inhibit their use of technology in the classroom? •Which of the learning management systems available today is most cost-efficient? 14 Assessment Questions •When is face-to-face instruction better than online? When is virtual better? How are they different? •How does giving student’s feedback on their work via technology affect how well they think critically? •How does technology meet different learning styles so that students are more engaged with the material? •How can the use of technology improve learning in large-enrollment classes? •How does access to Internet resources affect students’ ability to conduct empirical inquiry? Level of Analysis To develop accurate assessment questions, you must identify the unit or level of analysis. Is assessment for an individual student, a course, a program, or an institution? Traditionally, assessment is about aggregate information—students as a group within courses, programs, or institutions. Table 1 shows the interplay of the level of analysis with the assessmentevaluation spectrum. The columns represent steps on the continuum from assessment to evaluation; the rows identify the level of analysis; and each cell shows a sample question. Seeing common issues categorized may help in developing clear questions. Table 1. Level of Analysis Versus Continuum of Assessment to Evaluation Level of Analysis Continuum of Assessment to Evaluation General Assess ment Technology Assessment 15 Technology Evaluation Staffing Evaluatio n Operations and Efficiency Evaluation Individual Student How well is the How does student the performing? student’s proficiency with technology affect how well that student performs? Does the student have access to technology needed for his or her major? How effective is technology support for the student? Is the student satisfied with access to technology overall? Classroom or How well do Specific Event students understand what I’m teaching in this class period? By using a clicker system in my classroom , can I tell how well students understan d this topic, right now? What is the best technology to help me teach this topic? How well is the support staff performing in support of the technology needed for this specific topic? What other faculty teach this topic, and how can you share the technology? Course or How well do Specific Event students meet the outcomes and objectives for this course? Does the use of simulatio n software increase students’ understan ding of the course objectives ? Which clicker system works with other technology (hardware/s oftware) within this room? How well is the support staff performing in support of this course? Are there issues for operation of this course related to other courses? Program Are students required to bring laptops to What are the technology expectations and needs of students in How much will the use of online grading reduce the How does the number of students and faculty within this How well do students integrate their knowledge and abilities from 16 different courses into a fuller understanding of their profession? Division, College, Institution What do you or know about the overall abilities of those who graduate from this institution? college this better program? able to meet the program outcomes related to problem solving? need for TAs within the program? program influence the cost of technology for this program? In the education al environm ents that use technolog y, how well do students master fundamen tals, intellectu al discipline, creativity, problem solving, and responsibi lity? How does the infusion of technology across the curriculum impact the need for support staff? Are you managing the technology within the university effectively and efficiently? How can you assure that faculty and students have access to the most effective technologies for supporting teaching and learning? To make improvements, you must first decide what types of improvements are needed. For example, if students in large classes are not learning the material, appropriate assessment evidence can inform decisions about what technology to employ to improve that learning. Accountability is often linked with assessment, particularly when the audience includes the public, state legislatures, or accrediting agencies, 11 each of whom asks for proof that students are achieving stated learning 17 outcomes.12 Assessment can provide the information called for in these circumstances. Defining Interrelationships Assessing the impact of technology on student learning is difficult. As much as we’d like to ask what impact technology has on student learning, this question cannot be answered because technology interacts with many variables—student preparation and motivation, how the student or instructor uses technology, and how well the environment supports learning. Assessment questions should move away from an emphasis on software and hardware, focusing instead on what students and faculty do with software and hardware. Assessment programs should include an understanding of how the relationships among learners, learning principles, and learning technologies affect student learning. Instead of asking what impact technology has on student learning; ask how you can incorporate the best-known principles about teaching and learning, using technology as a tool for innovation. For example, a report published by the Association of American Colleges and Universities13 articulates the principle of empowering students to become better problem solvers, to work well in teams, to better use and interpret data, and to increase their understanding of the world. How can technology facilitate this? Technology can help establish effective learning environments by bringing real-world problems into the classroom; allowing learners to participate in complex learning; providing feedback on how to improve reasoning skills; building communities of instructors, administrators, and students; and expanding opportunities for the instructor’s learning.14 Assessment is important: “The tools of technology are creating new learning environments, which need to be assessed carefully, including how their use can facilitate 18 learning, the types of assistance that teachers need in order to incorporate the tools into their classroom practices, the changes in classroom organization that are necessary for using technologies, and the cognitive, social, and learning consequences of using these new tools.”15 Due to the complexity of these interrelationships, it helps to focus on measurable components. Think about learning, learning principles and practices, and learning technologies. Define the issues within each category. Consider the following questions as you identify the issues you want to measure: Learners •What are the learners’ backgrounds? •What knowledge, skills, and technology literacies do they already have? •What are their demographics? •What attitudes do they hold about technology? •Do students’ learning styles differ? Learning Principles and Practices •Where and when do you use technology? Internal/external to the classroom? Before/during/after class sessions? In virtual labs? •How is technology used? To share notes, augment lectures? To simulate critical thinking? To link graphics to real-time data? •What instructional practices are used in the course? Active learning? Group problem solving? Collaborative learning? Learning Technologies •How well does the technology work, in terms of functionality, support, and usability? 19 •What specific technologies or tools do you use, including software (simulation, communication, visual) and hardware (document camera, laptops, iPods, clickers)? Focus on Student Learning Identifying a specific technology and learning situation allows you to focus on student learning. For example, years ago, engineering professionals sketched ideas with pencil and paper. Today, CAD programs extend students’ ability to accurately manipulate a creative reality of the problem. Consider this question: When using CAD technology for modeling in a laboratory setting, are students able to think more deeply about an issue or have a broader understanding? Because assessment focuses on student learning, however, you must clarify what you want to know about student learning. CAD technology allows for nonlinear thinking—thinking in more than two dimensions—which lets an engineer creatively engage more ideas and variations without worrying about the technical skill of sketching.16 Clarifying the student-learning portion, the question above can be modified as follows: When using CAD technology for modeling in a laboratory setting, how are the students’ critical thinking and multidimensional problem-solving skills transformed? Outcomes First, Technology Second The way technology is used does not cause students to learn better, but there is a correlation, a connection. Assessing this connection is the most critical part of the assessment process and illustrates the difficulty of using traditional assessment techniques in the area of technology. 20 At the course or academic program level, faculty determine what they want students to learn (outcomes), often using Bloom’s taxonomy17 to clarify the level of learning (definition, synthesis, analysis, and so on). When you assess how well students learn at the course or academic program level, you don’t typically ask about the connection between how the information was taught and how well the students learned—not, at least, in the first round of the assessment cycle. Initially, faculty develops outcomes and then measures how well students achieve them. If faculty finds that students have met the outcomes, they don’t ask how the material was taught. The results do not call for improvement, and so no further assessment is conducted. If students don’t meet the outcomes, however, faculty begins to ask how the material was taught, when it was taught, and whether it should be taught differently. Therefore, by assessing the interrelationships among technology, learners, and pedagogy, you start with the second round of a traditional assessment cycle. You have not stopped to do the first round, which determines what students are learning, regardless of the learner characteristics or pedagogy. The results from course and academic program assessments can make questions about technology more meaningful. Course or program assessment results help focus attention on areas (outcomes) where students have difficulty learning. Focusing on what students are not learning well can refine the assessment questions. For example, does the use of simulation help students better understand how to solve problems that, prior to the simulation, were difficult for them to understand? Five Steps to Developing an Assessment Question The assessment cycle starts with developing appropriate questions. To accurately assess technology’s impact on student learning, carefully decide what you want to know. 21 Step 1: Determine where along the continuum of assessment to evaluation your question resides. Is your question related to assessment of student learning or evaluation of resources? Step 2: Resolve the level of analysis. Is your inquiry about an individual student, a specific course, a program, a division, or an institution? Step 3: Establish the purpose of your inquiry. Is it for improvement, decision making, or accountability? Step 4: Characterize the interrelationships among learners, learning principles, and learning technology to further focus your question. Step 5: Define student learning. What do you want students to know, think, or do in relation to the other parts of your question? Use of course or program outcomes or prior assessment results can differentiate the learning related to your question. Applying these steps results in improved questions that more fully address the impact technology has on student learning. Below is an example illustrate the process. Example 1 Does the help of an academic technology specialist create effective learning experiences for students? Step 1: The focus is on student learning, which makes this an assessment question. Step 2: The level of analysis is not clear in the question. Is it for a specific course? Is it an institution-level question? If so, the analysis would cross multiple courses. The level of analysis changes how the assessment would be conducted. Step 3: If the purpose is to improve a specific course, the question needs to include that purpose. 22 Step 4: This question asks about the interrelationship between pedagogy and technology—whether the changes have an effect. Therefore, the question can be modified for the specific technologies and pedagogies used. Step 5: To make this an assessment question and not an evaluation question, it needs to reflect specifically what students are learning. Why was this course changed? One reason might be because students in the past did not learn the material to the instructor’s satisfaction. Was it a depth-of-knowledge issue? Could students describe the basic knowledge but not apply that knowledge to other situations? In this example, then, the five steps lead to a better question. Improved question: For this course, did the change in pedagogy to a more interactive classroom, including the use of technology (changes based on the advice of an academic technology specialist enable students to use CAD modeling systems and specialized software applications to visualize, develop, and analyze the design of a product at the level appropriate for potential employers? Defining Methods Once a question has been established, the second component in the assessment cycle is to select the most appropriate assessment methods, either direct or indirect. Direct methods judge student work, projects, or portfolios developed from the learning experiences. Some consider this “authentic” assessment. Indirect methods use opinions of students or others to indicate student abilities. In many cases, there is no ideal assessment method, but matching the method to the question is more important than having a perfect, well-controlled method: “Far better an approximate answer to the right question…than an exact answer to the wrong question.” 23 18 Direct Assessment Methods •Course-based performance, including tests, essays, portfolios, homework, journals, presentations, projects, and capstone experienced-based courses •National test scores, at entry, midpoint, and graduation •Certification exams and professional licensure • Case studies •Thesis or dissertation work •Qualifying exams for graduate work •Longitudinal or cross-sectional comparisons (knowledge, time to do task, problem-solving skills) Indirect Assessment Methods •Surveys completed by incoming, enrolled, withdrawn, and graduating students, as well as by alumni and employers •Surveys and inventories related to behavior or attitude changes (pre- and post-educational experience) •Focus group meetings of students, staff, faculty, employers, or community agencies •Student development transcripts (record of out-of-class experiences) •Tracking of course-taking patterns •Student reflection on work, portfolios, and other activities 24 IV. CONCLUSION Technology in the classroom has a great significance in the teaching and learning of the pupils or students if the use of technology is supported by significant investments in hardware, software, infrastructure, professional development, and support services by the government and the stakeholders as well. While complex factors have influenced the decisions for where, what, and how technology is introduced into our nation's school systems, ultimately, the schools and other key people will be held accountable for these investments and sustain other needs as necessary. ICT in the classroom has the power to increase motivation and learner engagement and help to develop life-long learning skills. This claim is also true and a mandate in the article XIV section 10 of the 1987 Philippine constitution as discussed earlier. However, even with these technologies incorporated inside the classroom, it is still an evident fact that teachers are still the best “technology” that provides the best learning experience for pupils and students in their pursuit for excellence. 25 V. BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. For a history of the development of assessment, see Ewell, P. (2002). An emerging scholarship: A brief history of assessment. In T. W. Banta and associates (Eds.), Building a Scholarship of Assessment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 2. Twigg, C. A. (2004). Improving learning and reducing costs: Lessons learned from round II of the Pew grant program in course redesign. Troy, NY: Center for Academic Transformation. 3. Hu, S., & Kuh, G. D. (2001, November 24). Computing experience and good practices in undergraduate education: Does the degree of campus “wiredness” matter? Education Policy Analysis Archives, 9(49). Retrieved June 24, 2006, from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v9n49.html; Kuh, G. D., & Vesper, N. (2001). Do computers enhance or detract from student 26