20131205091510151

advertisement

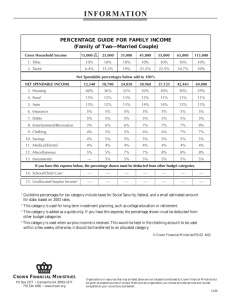

Modelling large-scale atmospheric circulations using semi-geostrophic theory Mike Cullen and Keith Ngan Met Office Colin Cotter and Abeed Visram (Imperial College), Bob Beare (Exeter University) © Crown copyright Contents This presentation covers the following areas • Background • Semi-geostrophic scaling • Properties of the large-scale regime • Application to validating numerical models • Application to boundary layer-free atmosphere interaction © Crown copyright Met Office Background © Crown copyright Governing equations On all relevant scales, the atmosphere is governed by the compressible Navier-Stokes equations, the laws of thermodynamics, phase changes and source terms The solutions of these equations are very complicated, reflecting the complex nature of observed flows The accurate solution of these equations would require computers 1030 times faster than now available Therefore cannot guarantee that numerical model solutions will be useful © Crown copyright Uses of reduced models Show why the large scales can be predicted well, even though system is nonlinear. Validating numerical models. Understanding the solution of the governing equations in particular regimes. © Crown copyright Method Characterise regime using appropriate asymptotic limit Derive asymptotic limit equations satisfying basic conservation properties (e.g. mass, energy) Show that they can be solved. Prove that solutions of the Euler or NavierStokes equations converge to them at the expected rate-validating the scale analysis. Include the error estimate when making predictions. © Crown copyright The semi-geostrophic scaling © Crown copyright Euler-Boussinesq system Illustrate with Euler-Boussinesq system with constant rotation in plane geometry and a free upper boundary. 𝐷𝑡 𝑢 + 𝑓𝑒3 × 𝑢 + 𝛻𝑝 + 𝜌𝑔𝑒3 = 0 𝐷𝑡 𝜌 = 0 𝛻∙𝑢 =0 𝜕ℎ 𝜕ℎ 𝜕𝑡 ℎ + 𝑢1 + 𝑢2 = 𝑢3 𝜕𝑥1 𝜕𝑥2 © Crown copyright Initial and boundary conditions Solve on [0,τ)xΩ(t) with Ω 𝑡 = Ω2 × 0, ℎ 𝑡, 𝑥1 , 𝑥2 ⊂ ℝ3 ; Ω2 ⊂ ℝ2 𝑢 ∥ 𝜕Ω 𝑡 𝑥3 = ℎ 𝑝 𝑡, 𝑥1 , 𝑥2 , ℎ 𝑡, 𝑥1 , 𝑥2 = 𝑝ℎ ) 𝑢 0, 𝑥 = 𝑢0 𝑥 , 𝜌 0, 𝑥 = 𝜌0 𝑥 , ℎ(0, 𝑥) = ℎ0 (𝑥) © Crown copyright Scaled equations Consider rotation dominated limit, ε=U/(fL) (Rossby number)=(H/L)2 𝜀𝐷𝑡 𝑢 1,2 𝑢 + −𝑢2 , 𝑢1 + 𝛻 1,2 𝑝 = 0 𝜀 2 𝐷𝑡 𝑢3 + 𝛻3 𝑝 + 𝜌 = 0 The other equations are unchanged. © Crown copyright Semigeostrophic equations Define the geostrophic wind by 𝛻 1,2 𝑝 + −𝑢𝑔2 , 𝑢𝑔1 = 0, 𝑢𝑔3 = 0 then the geostrophic wind by 𝛻 ∙ 𝑢𝑔 = 0; 𝑢 = 𝑢𝑔 + O 𝜀 𝜀𝐷𝑡 𝑢𝑔 + −𝑢2 , 𝑢1 , 0 + 𝛻𝑝 + 𝜌 = O 𝜀 2 The other equations are unchanged © Crown copyright Properties of solutions © Crown copyright Domain of validity This (Philips type II) scaling requires the Froude number to be O(Rossby½). This implies that the horizontal scale is larger than the Rossby radius LD, or the aspect ratio is less than f/N. Disturbances confined to the troposphere satisfy this for length scales>~1000km in mid-latitudes. In this regime, PV anomalies are dominated by static stability anomalies, and the energy by the APE. Rossby waves are only weakly dispersive. © Crown copyright Variable Coriolis effect needed whenever SG applicable (but not in ocean where LD smaller) Properties The total velocity u=(u,v,w) is computed diagnostically, not prognostically. It can take any size. If Du/Dt is large compared to Dug/Dt the scale analysis will be inconsistent and the solutions unphysical. If Q has negative eigenvalues the state is unstable and the flow unbalanced. SG cannot be solved in this case. Can be proved that if Q is positive definite at t=0, there is always a solution of SG that preserves this indefinitely. © Crown copyright Properties II While det Q is conserved with constant f, and only changes slowly with variable f, individual eigenvalues can deteriorate. This is a mechanism for extreme reaction to forcing. Moisture reduces the effective static stability, so reaction to forcing is much stronger. © Crown copyright Properties III Q is positive definite regardless of the sign of f. The condition that Q is positive definite is very severe at the equator; p cannot vary in the horizontal. The ageostrophic flow maintains this against forcing that varies in the horizontal (Hadley and Walker circulations). In general the ageostrophic flow filters small scales from the forcing and limits the effect on the large scales. © Crown copyright This is only realistic if the forcing is on a slow time scale. Persistent of eddies Consider the difference between SG shallow water flow, with depth h, and 2d incompressible flow. In SG, a vortex in ug is naturally an anomaly in h. There is no induced flow outside the vortex. In effect the vortex is shielded. In 2d Euler a vortex has an effect for a long distance unless shieldedbut this is not natural. This prevents an upscale energy cascade. The 2d turbulence scaling argument for an upscale energy cascade does not apply in this regime because PV and energy anomalies both scale with h. © Crown copyright Observed spectra If 2d turbulence theory applies, expect -3 spectrum at large scales, and -5/3 where 3d effects take over. Examples shown for 2010-11 winter. Observed spectra do not show any uniform behaviour on largest scales. Beyond wavenumber 7 there is a systematic energy decrease with k (-5/3 law). Data are 3 day averages of 200hpa geopotential, spectra are in longitudinal direction averaged from 30N-60N. © Crown copyright Evolution of spectra at 200hpa © Crown copyright Evolution of spectra at 200hpa © Crown copyright Evolution of spectra at 200hpa © Crown copyright Validation of numerical models (with Abeed Visram and Colin Cotter) © Crown copyright Numerical test The SG solution is invariant (in this problem) to rescaling x1 to βx1, u1 to βu1 and f to β-1f. Then ε becomes βε. Solve the Euler equations using a fully implicit semi-Lagrangian method. SG solution computed using fully Lagrangian particle method. The latter has been proved to converge to the SG solution. SG solution maintains Lagrangian conservation laws and exact geostrophic and hydrostatic balance. © Crown copyright Euler obeys the same Lagrangian conservation laws. Plot rms value of u2 Effect of resolution © Crown copyright Convergence as β reduced © Crown copyright Converence to geostrophic balance © Crown copyright Comments Model gives the correct rate of convergence to balance. It reproduces the periodic lifecycles rather better than Nakamura and Held (1989) who used Eulerian advection and artificial viscosity. Peak amplitude not predicted. This is because nonlinearity stops the linear growth too quickly. Implicit diffusion due to the limiters in the advection scheme balances the frontogenesis. Lagrangian conservation under advection is badly violated. © Crown copyright Enforcing conservation Illustrate the difference between (ρa)2 and (ρ2)a normalised by ρ2 under advection for one timestep using smooth prefrontal flow fields. ρ V 1 1.4E-3 1.0E-4 2 5.3E-4 3.0E-5 4 4.3E-4 9.8E-6 Conv rate 0.88 1.70 L2 1 2.9E-5 6.2E-6 2 6.4E-6 4 rate L∞ Conv © Crown copyright 1 2.2E-4 2.2E-5 2 1.1E-4 6.6E-6 4 3.1E-5 2.1E-6 1.41 1.70 1 6.1E-6 1.8E-6 9.9E-7 2 1.6E-6 3.2E-7 2.9E-6 2.2E-7 4 4.2E-7 7.2E-8 1.67 2.41 1.92 2.33 L∞ L2 Enforcing conservation Illustrate the difference between (ρa)2 and (ρ2)a normalised by ρ2 under advection for one timestep using sharp post frontal flow fields. ρ V 1 8.7E-2 1.7E-1 2 8.7E-1 9.5E-1 4 1.9E0 1.9E-0 Conv rate -2.21 -1.70 L2 1 3.1E-3 4.3E-3 2 1.4E-2 4 rate L∞ Conv © Crown copyright 1 1.3E-2 1.5E-2 2 3.3E-2 3.2E-2 4 5.4E-2 8.1E-2 -1.02 -1.21 1 4.0E-4 3.9E-4 1.7E-2 2 7.0E-4 7.9E-4 1.3E-2 2.1E-2 4 6.8E-4 4.7E-4 -1.05 -1.16 -0.07 -0.40 L∞ L2 Comments If balance and Lagrangian conservation both enforced, should get convergence to SG which imposes these constraints. Explanation of failure to get adequate lifecycle is that variance is dissipated at the front, There is no reason why Euler solutions should not be able to maintain Lagrangian conservation. Obvious remedy is to improve Lagrangian conservation (ideally enforce it-but this is very hard in practice). © Crown copyright Extension to the atmospheric boundary layer (with Bob Beare) © Crown copyright Basic idea Consider flow in 2d cross section with realistic boundary layer. In particular, mixing is strongly stability dependent. Seek to derive scaled equations that give SG in the free atmosphere and Ekman balance within boundary layer. These equations should have negative definite energy tendency in absence of thermal forcing. Seek to explain observed phenomena © Crown copyright Equations 2d cross-section as before p u1 K m Dt u1 fu 2 x1 x3 x3 u2 K m Dt u2 fU fu1 x3 x3 p Dt u3 g 0 x3 Dt Fb u 0 © Crown copyright Scaled equations Let Ek=Km/fh2, h is boundary layer depth. Assume Ek=O(1) in boundary layer, 0 elsewhere. Do not assume u1=εu2. p ˆ u1 K m Dt u1 u2 x1 x3 x3 ˆ u2 K m Dt u2 U u1 x3 x3 p 2 Dt u3 0 x3 D Fˆ t © Crown copyright u 0 b Geostrophic Ekman (geotriptic) balance balance Steady state balances Geostrophic wind Pressure gradient Coriolis Ekman balanced wind Pressure gradient Coriolis Boundary layer drag Prognostic models Planetary geostrophic (PG) Semi-geostrophic (SG) Quasi-geostrophic (QG) Planetary-geotriptic (PGT) Semi-geotriptic (SGT) Leading order balance Ekman balance p ˆ u1 K m u2 x1 x3 x3 ˆ u2 K m U u1 x3 x3 In general, define Ekman balanced wind by p ˆ u1e K m u2e x1 x3 x3 © Crown copyright ˆ u2 e K m U u1e x3 x3 SG consistent balance Replace u by ue in Dt term, get to O(ε2) p ˆ u1 K m Dt ue1 u2 x1 x3 x3 ˆ u2 K m Dt ue 2 U u1 x3 x3 p 0 x3 D Fˆ t u 0 © Crown copyright b Sustainable balance These equations do not have a negative definite energy integral. Instead to O(ε) set ˆ u1 K m ue1 u1 Dt ue1 ue 2 u2 x3 x3 ˆ K m ue 2 u2 Dt ue 2 ue1 u1 x3 x3 p 0 x3 D Fˆ t © Crown copyright u 0 b Comments These (SGT) equations are no more accurate in the boundary layer than just imposing u=ue. However, that does not give a negative definite energy integral either. SGT is consistent with SG in the free atmosphere. Does not appear possible to get O(ε2) accuracy sustainably with models of this type. Probably the boundary layer cannot be ‘balanced’ to this order. © Crown copyright Diagnostic equation for u Calculate u required to maintain Ekman balance relation for ue (Sawyer-Eliassen equation in SG case). Gives diagnostic equation for stream function which determines (u1,u3). Then deduce u2. Diagnostic equation is elliptic if the state is statically stable, and satisfies an inertial stability condition reinforced by friction. © Crown copyright Low level jet simulation Use analytically generated jet profile, wind in x2 direction. Profiles of u2 and ρ-1 (illustrating boundary layer structure): © Crown copyright Diagnosed u3 Positive values bold. Max negative value much bigger than given by Ekman pumping. © Crown copyright Diagnosed u2 u2 in bold, ue2 feint. © Crown copyright Comments Enhanced low level jet seen, as often observed. This is a different mechanism from the nocturnal collapse of the boundary layer-also often observed. This model very useful in the tropics, where friction can support a horizontal pressure gradient, while geostrophic dynamics cannot. © Crown copyright Questions © Crown copyright