Communicating in a Crisis Is Different

Crisis & Emergency

Risk Communication

Barbara Reynolds, Ph.D.

Communicating in a crisis is different

In a serious crisis, all affected people . . .

– Take in information differently

– Process information differently

– Act on information differently

In a catastrophic event: communication is different

Be first, be right, be credible

The Risk of Disasters

Is Increasing

Increased terrorism

Population density

Aging U.S. population

International travel speed

Emerging diseases

What the public seeks from your communication

5 public concerns. . .

1.

Gain wanted facts

2.

Empower decisionmaking

3.

Involved as a participant, not spectator

4.

Provide watchguard over resource allocation

5.

Recover or preserve well-being and normalcy

Crisis and Emergency Risk

Communication impacts

5 organizational concerns -- you need to. . .

1.

Execute response and recovery efforts

2.

Decrease illness, injury, and deaths

3.

Avoid misallocation of limited resources

4.

Reduce rumors surrounding recovery

5.

Avoid wasting resources

Crisis Communication Lifecycle

Precrisis Initial Maintenance Resolution Evaluation

• Prepare

• Foster alliances

• Develop consensus recommendations

• Test message

• Evaluate plans

• Express empathy

• Provide simple risk explanations

• Establish credibility

• Recommend actions

• Commit to stakeholders

• Further explain risk by population groups

• Provide more background

• Gain support for response

• Empower risk/benefit decisionmaking

• Capture feedback for analysis

• Educate a primed public for future crises

• Examine problems

• Gain support for policy and resources

• Promote your organization’s role

• Capture lessons learned

• Develop an event SWOT

• Improve plan

• Return to precrisis planning

Precrisis Phase

Prepare

Foster alliances

Develop consensus recommendations

Test message

Evaluate plans

Initial Phase

Express empathy

Provide simple risk explanations

Establish credibility

Recommend actions

Commit to stakeholders

Maintenance

Further explain risk by population groups

Provide more background

Gain support for response

Empower risk/benefit decisionmaking

Capture feedback for analysis

Resolution

Educate “primed” public for future crises

Examine problems

Gain support for policy and resources

Promote your organization’s role

5 communication failures that kill operational success

1.

Mixed messages from multiple experts

2.

Information released late

3.

Paternalistic attitudes

4.

Not countering rumors and myths in real-time

5.

Public power struggles and confusion

5 communication steps that boost operational success

1.

Execute a solid communication plan

2.

Be the first source for information

3.

Express empathy early

4.

Show competence and expertise

5.

Remain honest and open

Psychology of a Crisis

What Do People Feel Inside When a Disaster Looms or Occurs?

Psychological barriers:

1.

Denial

2.

Fear, anxiety, confusion, dread

3.

Hopelessness or helplessness

4.

Seldom panic

5.

Vicarious rehearsal

What Is Vicarious Rehearsal?

The communication age gives national audiences the experience of local crises.

These “armchair victims” mentally rehearse recommended courses of actions.

Recommendations are easier to reject the farther removed the audience is from real threat.

Individuals at risk —the cost?

Demands for unneeded treatment

Dependence on special relationships (bribery)

MUPS —Multiple Unexplained Physical

Symptoms

Self-destructive behaviors

Stigmatization

Community at risk —the cost?

Disorganized group behavior (unreasonable demands, stealing)

Rumors, hoaxes, fraud, stigmatization

Trade/industry liabilities/losses

Diplomacy

Civil actions

Communicating in a Crisis Is Different

Public must feel empowered – reduce fear and victimization

Mental preparation reduces anxiety

Taking action reduces anxiety

Uncertainty must be addressed

Decisionmaking in a Crisis Is Different

People simplify

Cling to current beliefs

We remember what we see or previously experience (first messages carry more weight)

People limit intake of new information (3-7 bits)

How Do We Communicate

About Risk in an Emergency?

All risks are not accepted equally

Voluntary vs. involuntary

Controlled personally vs. controlled by others

Familiar vs. exotic

Natural vs. manmade

Reversible vs. permanent

Statistical vs. anecdotal

Fairly vs. unfairly distributed

Affecting adults vs. affecting children

Be Careful With Risk

Comparisons

Are they similarly accepted based on

– high/low hazard (scientific/technical measure)

– high/low outrage (emotional measure)

A. High hazard

C. Low hazard

B. High outrage

D. Low outrage

Risk Acceptance Examples

Dying by falling coconut or dying by shark

– Natural vs. manmade

– Fairly vs. unfairly distributed

– Familiar vs. exotic

– Controlled by self vs. outside control of self

Risk Communication

Principles for Emergencies

Don’t overreassure

Considered controversial by some.

A high estimate of harm modified downward is much more acceptable to the public than a low estimate of harm modified upward.

Risk Communication

Principles for Emergencies

When the news is good, state continued concern before stating reassuring updates

“Although we’re not out of the woods yet, we have seen a declining number of cases each day this week.”

“Although the fires could still be a threat, we have them 85% contained.”

Risk Communication

Principles for Emergencies

Under promise and over deliver . . .

Instead of making promises about outcomes, express the uncertainty of the situation and a confident belief in the “process” to fix the problem and address public safety concerns.

Risk Communication

Principles for Emergencies

Give people things to do - Anxiety is reduced by action and a restored sense of control

Symbolic behaviors

Preparatory behaviors

Contingent “if, then” behaviors

3-part action plan

Must do X

Should do Y

Can do Z

Risk Communication

Principles for Emergencies

Allow people the right to feel fear

Don’t pretend they’re not afraid, and don’t tell them they shouldn’t be.

Acknowledge the fear, and give contextual information.

Messages and

Audiences

Judging the Message

Speed counts – marker for preparedness

Facts – consistency is vital

Trusted source – can’t fake these

Public Information Release

What to release

When to release

How to release

Where to release

Who to release

Why release

Audience Relationship to

Event

Match Audiences and

Concerns

Audiences

Victims and their families

Politicians

First responders

Trade and industry

Community far outside disaster

Media

Concerns

Opportunity to express concern

Personal safety

Resources for response

Loss of revenue/liability

Speed of information flow

Anticipatory guidance

Family’s safety

5 Key Elements To Build Trust

1.

Expressed empathy

2.

Competence

3.

Honesty

4.

Commitment

5.

Accountability

Emergency Information

Any information is empowering

Benefit from substantive action steps

Plain English

Illustrations and color

Source identification

What does the public want to know?

Can you tell me more about the attack

– “What caused it, why, what is the reason behind it?”

– “Will there be more attacks?”

How long is the emergency

– “How long is the event going to last?”

– “How long is this ‘radiation’ going to last?”

Accuracy of

Information

__________

Speed of

Release

Empathy

+

Openness

CREDIBILITY

+ =

Successful

Communication

TRUST

Initial Message

Must

Be short

Be relevant

Give positive action steps

Be repeated

Initial Message

Must Not

Use jargon

Be judgmental

Make promises that can’t be kept

Include humor

Sources of Social Pressure

What will I gain?

What will it cost me?

What do those important to me want me to do?

Can I actually carry it out?

The STARCC Principle

Your public messages in a crisis must be:

S imple

T imely

A ccurate

R elevant

C redible

C onsistent

Crisis

Communication

Plan

Elements of a Complete

Crisis Communication Plan

1.

Signed endorsement from director

2.

Designated staff responsibilities

3.

Information verification and clearance/release procedures

4.

Agreements on information release authorities

5.

Media contact list

6.

Procedures to coordinate with public health organization response teams

7.

Designated spokespersons

8.

Emergency response team after-hours contact numbers

9.

Emergency response information partner contact numbers

10.

Partner agreements (like joining the local EOC’s JIC)

11.

Procedures/plans on how to get resources you’ll need

12.

Pre-identified vehicles of information dissemination

Nine Steps of Crisis Response

Conduct assessment

(activate crisis plan)

Organize assignments

Prepare information and obtain approvals

3 4

5

Conduct notification

2

Release information to media, public, partners through arranged channels 6

Verify situation

1

Crisis

Occurs

7 Obtain feedback and conduct crisis evaluation

9

8

Conduct public education

Monitor events

Prepare Information and

Obtain Approvals

Execute steps in communication plan

Public information release for your agency:

– Top official

– Top communicator

– Top subject matter expert

Look once, check twice, release it and move on

Delegate what you can, prioritize what you can’t

First 48 Hours - Tools

Critical first steps checklist

Message template for news release

Press availability at site template

Public call tracking sheet

Media call triage sheet

Risk assessment for communication

Stakeholder/

Partner

Communication

Stakeholder/Partner

Communication

Stakeholders have a special connection to you and your involvement in the emergency.

They are interested in how the incident will impact them.

Partners have a working relationship to you and collaborate in an official capacity on the emergency issue or other issues.

They are interested in fulfilling their role in the incident and staying informed.

5 Mistakes With Stakeholders

Inadequate access

Lack of clarity

No energy for response

Too little, too late

Perception of arrogance

Stakeholders can be . . .

Advocate –maintain loyalty

Adversary –discourage negative action

Ambivalent –keep neutral or move to advocate

3 Reasons to expend energy on stakeholders during an emergency

They may . . .

Know what you need to know

Have points of view outside your organization’s

Communicate your message for you

5 steps in stakeholder preplanning

1.

Identify stakeholders

2.

Do an assessment

3.

Query stakeholders

4.

Prioritize by relationship to incident

5.

Determine level of “touch”

Community Relations! Why?

Community acceptance through community involvement

Resource multiplier for volunteer “door to door” communication

Involving stakeholders is a way to advance trust through transparency

Our communities, our social capital, are a critical element of our nation's security

Dealing With Angry People

Anger arises when people. . .

Have been hurt

Feel threatened by risks out of their control

Are not respected

Have their fundamental beliefs challenged

Sometimes, anger arises when . . .

Media arrive

Damages may be in play

High-Outrage Public

Meetings

“Do’s”

The best way to deal with criticism and outrage by an audience is to acknowledge that it exists.

(Don’t say, “I know how you feel.”)

Practice active listening and try to avoid interrupting.

State the problem and then the recommendation.

High-Outrage Public

Meetings

“Don’ts”

Verbal abuse! Don’t blow your stack.

– Try to bring along a neutral third party who can step in and diffuse the situation.

Don’t look for one answer that fits all.

Don’t promise what you can’t deliver.

Don’t lecture at the Townhall

Easy but not effective

Doesn’t change thoughts/behaviors

Instead, ask questions

Key: don’t give a solution, rather help audience discover solution

4 Questions to help people persuade themselves

1.

Start with broad open-ended historical questions

2.

Ask questions about wants and needs

3.

Ask about specifics being faced now

4.

Ask in a way to encourage a statement of benefits

2 simple tips to gain acceptance

1.

Accumulate “yeses”

2.

Don’t say “yes, but”—say “yes, and”

Six Principles of CERC

Be First: If the information is yours to provide by organizational authority —do so as soon as possible. If you can’t—then explain how you are working to get it.

Be Right: Give facts in increments. Tell people what you know when you know it, tell them what you don’t know, and tell them if you will know relevant information later.

Be Credible: Tell the truth. Do not withhold to avoid embarrassment or the possible “panic” that seldom happens. Uncertainty is worse than not knowing — rumors are more damaging than hard truths.

Six Principles of CERC

Express Empathy: Acknowledge in words what people are feeling —it builds trust.

Promote Action: Give people things to do. It calms anxiety and helps restore order.

Show Respect: Treat people the way you want to be treated —the way you want your loved ones treated —always—even when hard decisions must be communicated.

Terrorism and

Bioterrorism

Communication

Challenges

What’s Different in a

Terrorism Response?

Stronger reaction from the public

Multiple events occur

Incident location is a crime scene

Detection is delayed

Responders are at higher risk

Response assets are targets

Terrorism and Risk

Communication

Outside control of individual or community

Unfairly distributed

From untrusted source

Man-made

Exotic

Catastrophic

Federal Response Plan

FBI leads on information release in crisis management

FEMA leads on information release in consequence management

Transfer lead from the FBI to FEMA by Attorney

General

Core federal response:

DOJ/FBI DOE FEMA

DOD EPA HHS

Joint Information Center

FBI public information officer and staff

FEMA public information officer and staff

Other federal agencies’ PI staff

State and local PIOs

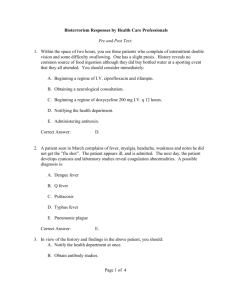

Bioterrorism Is Different

Medical and public health systems are usually the first to detect bioterrorism.

A delay is likely between the release of the agent and the knowledge that the occurrence is a bioterrorist act.

A short window of opportunity exists between the first cases and the second wave.

Natural Emerging Infectious

Disease or Bioterrorism?

Encephalitis

Hemorrhagic mediastinitis

Hemorrhagic fever

Pneumonia with abnormal liver function

Papulopustular rash (e.g., smallpox)

Descending paralysis

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea

Media Are Sure To Ask:

Is this bioterrorism?

Could this be bioterrorism?

Are you investigating this situation as possible bioterrorism?

Is the FBI involved in this investigation?

When will you be able to tell us whether or not this situation is bioterrorism?

Is It an Emerging Disease or

Undeclared Bioterrorism?

A possible response to media from public health officials is:

“We’re all understandably concerned about the uncertainty surrounding this outbreak, and we wish we could easily answer that question today.”

(continued on next slide)

Is It an Emerging Disease or

Undeclared Bioterrorism?

“For the sake of those who are ill or may become ill, our medical epidemiologists

(professional disease detectives) are going to first try to answer the following critical questions: (1) Who is becoming ill? (2) What organism is causing the illness? (3) How should it be treated? (4) How can it be controlled to stop the spread?”

(continued on next slide)

Is It an Emerging Disease or

Undeclared Bioterrorism?

“One question that disease investigators routinely ask is, “Could this outbreak have been caused intentionally?”

“We [organization name] must keep an open mind as data in this investigation are collected and analyzed.”

(continued on next slide)

Is It an Emerging Disease or

Undeclared Bioterrorism?

“Any specific questions about the FBI’s involvement regarding this outbreak investigation should be referred to them. However, the FBI and

[your organization] have a strong partnership regarding the investigation of unusual disease outbreaks and have worked comfortably together in the past in our parallel investigations.”

(Note: Don’t forget to coordinate this answer with the FBI.)

Strategic National Stockpile

(SNS)

12-hour Push Pack – 100 cargo containers

Air or ground ship

50 tons of medicine, medical supplies, equipment

Nerve agents, anthrax, plague, tularemia

Treat thousands of symptomatic and protect hundreds of thousands

Tale of Two Cities: Smallpox

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, experienced a Smallpox outbreak in 1894 of fairly major proportions, and caused urban rioting for about a month in the city streets —why?

New York City experienced the last Smallpox outbreak in this country in 1947. People stayed in line for hours, full days, and came back the next day in some cases with no unrest —why?

– Judith W. Leavitt, PhD, University of Wisconsin

SNS Communication Plan

Multi-language text

Methods for reproducing materials

Communication channels

Volunteers

Contractors

On-site interpreters

Not all SNS events the same

SNS communication assessment checklist

Working With the Media

Disasters Are Media Events

We need the media to be there.

Give important protective actions for the public.

Know how to reach their audiences and what their audiences need.

Response Officials Should

Understand that their job is not the media’s job

Know that they can’t dismiss media when they’re inconvenient

Accept that the media will be involved in the response, and plan accordingly

Response Officials Should

Attempt to provide all media equal access

Use technology to fairly distribute information

Plan to precredential media for access to

EOC/JOC or JIC

Think consistent messages

Response Officials

Should Not

Hold grudges

Discount local media

Tell the media what to do

How To Work With Reporters

Reporters want a front seat to the action and all information NOW.

Preparation will save relationships.

If you don’t have the facts, tell them the process.

Reality Check: 70,000 media outlets in U.S.

Media cover the news 24/7.

Media, Too, Are Affected by Crises

Verification

Adversarial role

National dominance

Lack of scientific expertise

Media and Crisis Coverage

Evidence strongly suggests that coverage is more factual when reporters have more information. They become more interpretative when they have less information.

What should we conclude?

Command Post

Media will expect a command post. Official channels that work well will discourage reliance on nonofficial channels.

Be media-friendly at the command post — prepare for them to be on site.

Media Beating on Your Door

Alternatives to “no comment” that give you breathing room:

– “We’ve just learned about this and are trying to get more information.”

– “I’m not the authority on this, let me have

XXXX call you right back.”

– “We’re preparing a statement on that now.

Can I fax it to you in about 2 hours?”

Media Availability or Press

Conferences “In Person” Tips

Determine in advance who will answer questions about specific subject matters

Keep answers short and focused —nothing longer than 2 minutes

Assume that every mike is “alive” the entire time

Sitting or standing?

Two press conference killers

Have “hangers on” from your organization circling the room

Being visible to the media/public while waiting to begin the press conference

Television Interview Tips

Don’t look at yourself on the TV monitor.

Look at the reporter, not the camera, unless directed otherwise.

Do an earphone check. Ask what to do if it pops out of your ear.

Writing for the Media

During a Crisis

The pressure will be tremendous from all quarters.

It must be fast and accurate.

It’s like cooking a turkey when people are starving.

If information isn’t finalized, explain the process.

Emergency Press Releases

One page with attached factsheet (can clear quicker)

Think of them as press updates, and prime media when to expect them

Should answer 5Ws and H for the time it covers

Press Statements Are Not

Press Releases

They are the official position.

May be used to counter a contrary view.

Not used for peer-review debate.

Offer encouragement to the public and responders.

Spokesperson

What the Public Will Ask First

Are my family and I safe?

What have you found that may affect me?

What can I do to protect myself and my family?

Who caused this?

Can you fix it?

What the Media Will Ask First

What happened?

Who is in charge?

Has this been contained?

Are victims being helped?

What can we expect?

What should we do?

Why did this happen?

Did you have forewarning?

Spokesperson Qualities

What makes a good spokesperson?

What doesn’t make a good spokesperson?

Role of a Spokesperson in an Emergency

Take your organization from an “it” to a “we”

Build trust and credibility for the organization

Remove the psychological barriers within the audience

Ultimately, reduce the incidence of illness, injury, and death by getting it right

Spokesperson Qualities

Be your organization; then be yourself.

What’s your organization’s identity?

Spokesperson Qualities

It’s more than “acting natural.” Every organization has an identity. Try to embody that identity.

Example: CDC has a history of going into harm’s way to help people. We humbly go where we are asked. We value our partners and won’t steal the show. Therefore, a spokesperson would express a desire to help, show courage, and express the value of partners. “Committed but not showy.”

Emergency Risk

Communication Principles

Don’t overreassure

Acknowledge that there is a process in place

Express wishes

Give people things to do

Ask more of people

Emergency Risk

Communication Principles

Consider the “what if” questions.

Spokesperson

Recommendations

Stay within the scope of your responsibility

Tell the truth

Follow up on issues

Expect criticism

Your Interview Rights

Know who will do the interview

Know and limit the interview to agreed subjects

Set limits on time and format

Ask who else will be or has been interviewed

Decline to be interviewed

Decline to answer a question

You Do Not Have the Right To:

Embarrass or argue with a reporter

Demand that your remarks not be edited

Demand the opportunity to edit the piece

Insist that an adversary not be interviewed

Lie

Demand that an answer you’ve given not be used

State what you are about to say is “off the record” or not attributable to you

Sensational or Unrelated

Questions

“Bridges” back to what you want to say:

“What I think you are really asking is . . .”

“The overall issue is . . .”

“What’s important to remember is . . .”

“It’s our policy to not discuss [topic], but what I can tell you . . .”

Watch Out For . . .

Machine gun questioning.

Reporter fires rapid questions at you. You respond, “Please let me answer this question.”

Feeding the mike and the pause.

Seldom will dead air make scintillating viewing, unless you’re reacting nonverbally. Relax.

Hot mike.

It’s always on—always—including during “testing.”

Watch Out For . . .

Reporter asks a sensational question and gives you an A or B dilemma.

Use positive words, correct the inaccuracies without repeating the negative, and reject A or B if neither is valid. (e.g., corn versus produce)

Explain, “There’s actually another alternative you may not have considered,” and give your message point.

Watch Out For . . .

Surprise prop.

The reporter attempts to hand you a report or supposedly contaminated item.

If you take it, you own it.

React by saying, “I’m familiar with that report and what I can say is” or “I’m not familiar with the report, but what is important” and then go to key message.

Effective Nonverbal

Communication

Do maintain eye contact

Do maintain an open posture

Do not retreat behind physical barriers such as podiums or tables

Do not frown or show anger or disbelief through facial expression

Do not dress in a way that emphasizes the differences between you and your audience

Grief in context

Circumstances of the death

Nature of the relationship

Experienced loss before

Any secondary losses

Communicating about loss

Ask clarifying questions

When possible, use the words the person uses

Say “you’re crying” instead of “you’re sad.”

Short statements of condolences (e.g., “this is a sad time,” or “you’re in my prayers”)

Use “death” or “dying,” not softer euphemisms like “expired,” or “heavenly reward”

Media and Public Health

Law

Model Emergency

Health Powers Act

Model public health law for states

Protection of civil liberties balanced with need to stop transmission of disease

Explain what law covers and why

Laws address: quarantine, vaccination, property issues, access to medical records

Model law draft – court order to quarantine someone, unless delay could pose an immediate threat

Protecting the Public from

Infectious Diseases

Detention – temporary hold

Isolation – separation from others for period of communicability

Quarantine – restricts activities of well persons exposed

First Amendment

“In the First Amendment the founding fathers gave the free press protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy. The press was to serve the governed, not the governors .”

– New York Times Co. v U.S., 403 U.S. 713 (1971)

Media’s right to acquire news

Press has right to acquire news from any source by any lawful means

No Constitutional right to special access

Information not available to the public:

– Crime scene

– Disasters

– Police station

– Hospital lab

– Other places

Access may be restricted

Interference with legitimate law enforcement action

Law enforcement perimeter

Crime scene

Disaster scene

Right to acquire information

Available or open to the public

Place or process historically open to the public:

– Hospitals?

– Jails?

– Courtrooms?

– Meeting/conference rooms?

Media’s right of publication

Once information is acquired

Ability to restrict information;

– Severely limited

– Heavy burden to prevent or prohibit

– Minneapolis Star Tribune v. U.S., 713 F Supp. 1308 (S. Minn, 1988)

Assisting the media

Inviting media on search or arrest in private citizen’s home is not protected by 1 st

Amendment and may result in civil liability

– Violation of 4th Amendment Rights

Employees access to media

Freedom of speech may be Constitutionally protected: if public value outweighs detrimental impact

May be required to follow chain of command

Ability to choose spokesperson:

– Police officer has no 1 st Amendment right to speak or act on behalf of department when not authorized to do so.

– Koch v. City of Portland, 766 P.2d 405 (Ore. App. 1988)

CDC’s principles of communication for public

Communication will be open, honest, and based on sound science, conveying accurate information

Information will not be withheld solely to protect

CDC or the government from criticism or embarrassment

Information will be released consistent with the

Freedom of Information Act

Freedom of Information Act

FOIA does not apply to state and local governments (most jurisdictions have a FOIAlike laws)

Principle of democracy is that citizens be informed about their government.

FOIA ensures that the federal government provides public maximum possible information

![Crisis Communication[1] - NorthSky Nonprofit Network](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005428035_1-f9c5506cadfb4c60d93c8edcbd9d55bf-300x300.png)