Fall 2015

advertisement

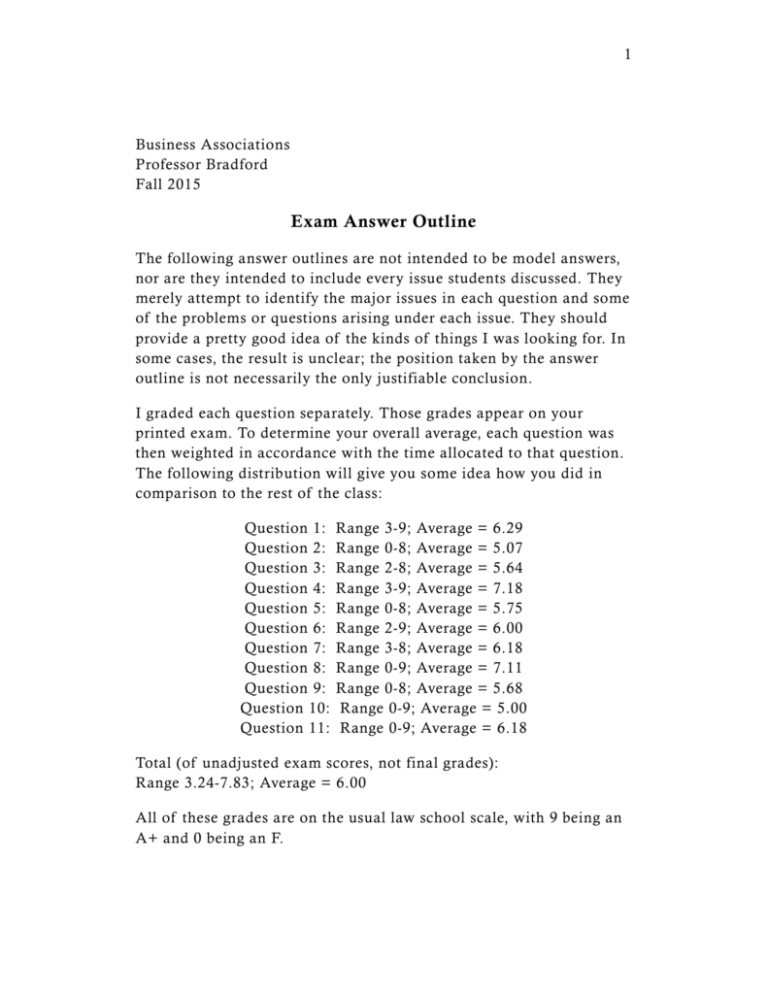

1 Business Associations Professor Bradford Fall 2015 Exam Answer Outline The following answer outlines are not intended to be model answers, nor are they intended to include every issue students discussed. They merely attempt to identify the major issues in each question and some of the problems or questions arising under each issue. They should provide a pretty good idea of the kinds of things I was looking for. In some cases, the result is unclear; the position taken by the answer outline is not necessarily the only justifiable conclusion. I graded each question separately. Those grades appear on your printed exam. To determine your overall average, each question was then weighted in accordance with the time allocated to that question. The following distribution will give you some idea how you did in comparison to the rest of the class: Question 1: Question 2: Question 3: Question 4: Question 5: Question 6: Question 7: Question 8: Question 9: Question 10: Question 11: Range 3-9; Average = 6.29 Range 0-8; Average = 5.07 Range 2-8; Average = 5.64 Range 3-9; Average = 7.18 Range 0-8; Average = 5.75 Range 2-9; Average = 6.00 Range 3-8; Average = 6.18 Range 0-9; Average = 7.11 Range 0-8; Average = 5.68 Range 0-9; Average = 5.00 Range 0-9; Average = 6.18 Total (of unadjusted exam scores, not final grades): Range 3.24-7.83; Average = 6.00 All of these grades are on the usual law school scale, with 9 being an A+ and 0 being an F. 2 If you have any questions about the exam or your performance on the exam, feel free to contact me to talk about it. 3 Question 1 Hogwarts’s Liability Hogwarts is liable on the contract only if Luna had authority to bind it. Luna’s status as a member of the LLC does not by itself make her an agent of the LLC or give her authority to act on its behalf. RULLCA § 301(a). But the LLC can still be bound by the member’s action under ordinary principles of agency law. See RULLCA § 301(b). As an employee, Luna clearly was an agent of Hogwarts, but that doesn’t answer the basic question: did she have the authority to enter into this contract? A principal such as Hogwarts can be liable on a contract if the agent, Luna had actual, apparent, or inherent authority. Restatement (Second) of Agency § 140. Luna clearly has neither actual nor inherent authority. Actual authority is created by conduct of the principal that, reasonably interpreted, causes the agent to believe the principal desires her so to act. RSA § 26. Hogwarts gave Luna only the authority to receive customer orders and pack them for shipment. No reasonable person could interpret that to include commissioning artwork for the lobby. Luna also has no inherent authority. Inherent authority is authority that is inherent in the position. Ordering artwork is not inherent in the position of fulfilling customer orders and RULLCA § 301(a) makes it clear that no authority is inherent in being a member of an LLC. Apparent authority is created by conduct or words of the principal that reasonably cause a third person to believe that the principal consent to have the action done on its behalf. RSA § 27. Apparent authority is created by the principal; Luna’s statement that she was authorized cannot create authority. 4 The secretary arguably indicated that Luna had authority, although her statement (“I’m sure it’s OK”) is a little ambiguous. But, unless the secretary herself had authority to say that on behalf of Hogwarts, her statement is not a statement by the principal that the third party could rely on. Granting authority is not inherent in the position of secretary, especially with respect to a transaction of which the secretary was unaware, and no person would reasonably rely on a secretary’s statement of an employee’s authority. Therefore, Hogwarts is not liable. Luna’s Liability If Hogwarts is somehow liable, then Luna would not be. The agent is not bound on a contract where the principal is disclosed. RSA § 320. Hogwarts is a disclosed principal because Alan is aware that Luna is acting for a principal and knows the identity of the principal. RSA § 4(a). If Hogwarts is not liable on the contract, then Luna would be liable to Alan. When she purports to make a contract on behalf of Hogwarts, Luna warrants that she has the power to bind Hogwarts. RSA § 329. If Hogwarts is not bound, then Luna is liable to Alan for breach of warranty. 5 Question 2 This provision is invalid. Section 16.02 of the RMBCA grants shareholders a right to inspect the compan y’s books and records. That inspection right is not conditioned on approval by the board of directors. And § 16.02(e) says that right of inspection “may not be abolished or limited by a corporation’s articles of incorporation or bylaws.” 6 Question 3 Omega may lawfully exclude this proposal only if it falls within one or more of the exclusions in Rule 14a-8(i), because all of the other requirements appears to be met. Other Requirements Marty appears to be eligible to use Rule 14a-8 because he owns at least $2,000 in market value of Omega’s voting securities. Rule 14a8(b)(1). The test is phrased in the alternative, so it ’s irrelevant that he doesn’t own 1% of the stock. However, he must have held this stock continuously for at least one year, which isn’t apparent from the question. If not, Omega may exclude his proposal. He is submitting only a single proposal and it’s less than 500-words, so he meets the requirements of (c) and (d). The SEC staff has indicated that material available at a hyperlink isn’t counted against the limit, as long as the hyperlink itself falls within the 500 -word limit. Finally, the problem indicates that Marty complied with the subsection (e) deadline set by Omega. Possible Exclusions (8) Director Elections This proposal could be excluded under subsection (i)(8)(ii). It would require existing directors to resign before their terms expire. It might also violate (i)(8)(i) by disqualifying current nominees from election, although it’s unclear if the amendment would apply to the current election. It also many fall within (i)(8)(iii). The statement about the current directors’ beliefs arguably questions “their competence . . . or character.” (3) Violation of Proxy Rules 7 The proposal might be excludable under subsection (i)(3). The proposal indicates that some directors believe the sun revolves around the earth, and that’s untrue. This could be proxy fraud in violation of Rule 14a-9, and thus a violation of the proxy rules. However, exaggeration like this might not be materially misl eading; one could argue that shareholders would see it for the exaggeration it is. (2) Violation of Law It’s possible that the proposal could be excludable under subsection (i)(2), if there is an applicable state and federal law that prohibits discrimination in employment because of beliefs of this type. But we would need to know if there is any such law. (1) Improper Under State Law This is probably not excludable under subsection (i)(1), even though it’s mandatory. Shareholders have the power to amend the bylaws under Delaware law, Del. § 109, and director qualifications are the time of process-oriented provision that the Delaware Supreme Court says are appropriate for inclusion in the bylaws. See CA, Inc. However, the requirement that existing directors resign my go beyond pure procedure and intrude on the removal provisions in Del. § 141(k). (10) Substantially Implemented The proposal would not be excludable under subsection (i)(10), even though Omega already has qualifications for directors, because it doesn’t have these particular qualifications, so such a requirement has not been substantially implemented. 8 Question 4 1. Cumulative Voting. One possibility is to provide for cumulative voting in the articles. If the corporation has cumulative voting, Larry, with 40% of the shares, is guaranteed to be able to elect at least two people to the board. 2. Class Voting for Directors. Another possibility is to issue two classes of shares, identical in every respect except for voting for directors. The articles could provide for two directors to be elected by the class that Larry holds, with the remaining three directors either chosen just by the class held by Curly and Moe or chosen by the holders of both classes. 3. Voting Agreement or Voting Trust. Another possibility is to have the three shareholders enter into a voting trust or voting agreement that obligates the trustee (in the case of a voting trust) or the shareholders (in the case of a voting agreement) to vote for two directors designated by Larry each year before the election. 4. Irrevocable Proxy. Curly and Moe could give Larry an irrevocable proxy to vote their shares. The problem with this method is that it would allow Larry to elected not just two directors, but all of the directors. 5. Shareholder Agreement. If they’re incorporated in a jurisdiction that has something like MBCA § 7.32, they could enter into an agreement providing who will be directors, in lieu of an election. See MBCA § 7.32(a)(3). 9 Question 5 The basic idea underlying Donahue—that those in control of the corporation should not be able to use their control to take unfair advantage of minority investors—seems right. But the cost of trying to protect against such unfairness exceeds the benefit of having such a rule. First, the investors themselves have chosen the corporate form. If they wanted partnership-like fiduciary duties, they could have formed a partnership. Or, even if they chose a corporation, the minority shareholder could have insisted on contractual protections against majority abuse. Applying the enhanced fiduciary duty in cases where a partnership was not chosen and no contractual protections were included upsets the bargain that the parties themselves made. This is justified by a vague assertion about what rights the minority investor would have wanted, without any actual evidence in most cases that the investor had such an expectation. The Donahue rule also guts the traditional business judgment deference that applies to corporate decision-making. The judge is forced to decide whether the action taken was for a legitimate business purpose or to freeze out the minority shareholder and then must engage in difficult balancing between the needs of the business and the interest of the shareholder in receiving a return on his or her investment. The result is exactly what the business judgment rule seeks to avoid: court scrutiny of every business decision and second guessing of business judgments by courts lacking expertise in business. The Donahue rule also results in ad hoc decision-making and uncertainty. The standard—general ideas of “fairness” and “fair play”—is vague and ambiguous. Even courts that agree on the application of the Donahue test can’t agree on exactly what it requires in particular circumstances. This makes it difficult for people running small businesses to know in advance what’s allowed and what isn’t 10 and encourages litigation by minority shareholders. This increases the legal risks and costs incurred by small businesses. 11 Question 6 A. Maximum Amount of Dividends Under Delaware law, a corporation may pay dividends either out of surplus or, if there is no surplus, out of the net profits for the current and/or immediately prior fiscal year. Del. § 170(a). The second , nimble-dividends provision doesn’t matter because there is a surplus and there have been no net profits either this year or in the prior year. Beta lost money both years. Surplus is defined as the excess of the net assets over stated capital, and net assets is defined as “the amount by which total assets exceed the total liabilities. Del. § 154. The stated capital is the sum of the capital accounts for both types of shares, based on the par value for those shares: $1,000 for common stock and $1,000 for preferred stock. See Del. § 154. Net assets is $155,000 - $140,000 = $15,000. Thus, surplus, is $15,000 - $2,000 = $13,000. The maximum amount of dividends is $13,000. B. Allocation of the Dividend The preferred stock has a $1/share dividend preference. Thus, each preferred shareholder must be paid $1/share before the common shareholders receive anything. However, that preference is cumulative, and no dividend was paid last year, so the preference is now a total of $2 for the two years of Beta’s existence. Thus, before any dividends are paid to the common shareholders, each preferred shareholder must be paid $2/share, for a total of $2,000. The preferred stock is non-participating, so that’s all they get; they don’t share in the payments to the common shareholders. The remaining $11,000 is split among the 2,000 common shares, so each common shareholder would receive $ 5.50/share. 12 Question 7 Delaware allows a provision in the articles like this that limits the liability of directors for money damages. Del. § 102(b)(7). However, there are four categories of liability that may not be limited: (1) breaches of the duty of loyalty; (2) action not in good faith or that involves intentional misconduct or a knowing viol ation of law; (3) a violation of the dividend restrictions; or (4) any transaction from which the director derives an improper personal benefit. None of the directors has any personal interest in the decisions concerning Gamma’s security system, so there’s no improper personal benefit and no violation of the duty of loyalty (except possibly for the “bad faith” part of the duty of loyalty, discussed below). This question also does not involve a violation of the dividend restrictions. Finally, there does not appear to be any intentional misconduct by the directors or a violation of law. Thus, the provision in the articles will protect the directors from liability unless their action was not in good faith. Bad faith includes several categories of behavior by directors. The first is conduct “motivated by an actual intent to do harm” to the corporation. In Re Walt Disney Company Derivative Litigation. There’s no evidence of anything like that here. The directors were trying to save money for the corporation, not to intentionally harm it. Bad faith also includes an intentional violation of applicable positive law. Disney. There’s no evidence of that here either. Nothing in the question indicat es the company was legally bound to institute additional security procedures. The final element of bad faith is when the directors “intentionally fail to act in the face of a known duty to act, demonstrating a conscious disregard” of their duties. Disney. Here, the directors failed to institute additional security procedures, bu t they weren’t completely disregarding their duties. They already had security procedures in place; they just decided that additional procedures were too costly given the risk. That, in retrospect, was a stupid decision, but “gross 13 negligence without any malevolent intent is not within the meaning of “bad faith.” Disney. The directors are liable only “if they knowingly and completely failed to undertake their responsibilities,” Lyondell Chemical Co. v. Ryan, and they haven’t done that here. They have some procedures in place and they evaluated whether to put additional procedures in p lace and decided not to. That, in retrospect, was a bad decision, possibly even a grossly negligent one, but it’s not bad faith. Since the directors are not guilty of any breach of duty that can’t be disclaimed in the articles, they will not be liable. 14 Question 8 The partnership is dissolved. Xerxes has a right to withdraw at any time by giving written notice. RULPA § 602. Xerxes has withdrawn, if his notice was written. He’s liable for damages if his withdrawal breaches the partnership agreement, id., but there’s nothing relevant in the partnership agreement, so he has no liability as a result of his withdrawal. The withdrawal of a general partner dissolves the partnership unle ss there is at least one other general partner at the time and the partnership agreement permits the business to be carrying on with the remaining partner. RUPA § 801(4). Xerxes was the only partner, so the exception does not apply. There’s a second exception that could apply, however. Within 90 days of Xerxes’ withdrawal, the partnership can continue if all partners agree in writing to continue and to appoint a new general partner. Id. That has not happened because Alpha did not agree to appoint Zelda as a general partner. Since a limited partnership must have a general partner, RUPA § 101(7), the partnership is dissolved under § 801(4). (The 90 days has now expired.) Lotta must be wound up, with the creditors paid and assets distributed to the partners in accordance with their allocation of profits and distributions. RUPA § 802(a); 807(a). If the partnership has insufficient assets to pay its creditors, Xerxes is personally liable for the difference. Section 403(b) imposes on him the liabilities of a partner in a general partnership and that includes personal liability for the obligations of the partnership. RUPA § 306(a). 15 Question 9 Because of her ownership of 50% of the stock of Regal, Mary clearly has a material personal interest in the lease transaction. If she were a corporate director, her involvement while failing to disclose that interest would clearly breach her duty of loyalty. See, e.g., HMG/Courtland Properties v. Gray. Further, absent disclosure, the approval by a disinterested person such as Chief would not protect her if she were a corporate director. Id. Full disclosure is necessary for approval by a disinterested body to cleanse the conflict of interest. See Del. § 144. However, this is not a corporation, but a manager-managed LLC. In a manager-managed LLC, the manager owes a fiduciary duty of loyalty. RULLCA 409((g)(1), but a member has no fiduciary duty solely by reason of being a member. RULLCA § 409(g)(5). There is no indication that Mary has any other relationship to the LLC, so Mary’s interest and non-disclosure would not breach any duty of loyalty. However, even in a manager-managed LLC, members owe an obligation of good faith and fair dealing. RULLCA § 409(d). That obligation applies whenever a member is discharging any duty or exercising any rights under the operating agreement. When Mary is urging the LLC to rent from Regal, she is exercising her right under the agreement to consult with Chief before major decisions. Arguing for the Regal contract without disclosing her personal interest in the deal might be a violation of the contractual obligation of good faith and fair dealing. It depends on how far a court is willing to extend this duty. Extending it to basically encompass a duty of loyalty, however, seems inconsistent with the drafters’ rejection of such a duty for members. 16 Question 10 Before partners are paid, the partnership’s assets “must be applied to discharge its obligations to creditors.” RUPA § 807(a). Creditors have priority over the partners’ equity interests. Thus, $20,000 of the remaining cash must be used to pay the debts. The remaining amount of $80,000 is distributable to the partners. The partners’ existing interest in the partnership is a total of $100,000 + $20,000 + $10,000 = $130,000. Since there is only $80,000 left, that means the partnership has suffered a loss of $50,000. That loss, like any other partnership loss, must be charged against the partners § 807(b). See also RUPA § 401(a)(2) (losses charged to partners’ accounts). The partnership agreement says nothing about the allocation of losses, so the default rule applies: partners bear losses “in proportion to the partner’s share of profits.” RUPA § 401(b). The partnership agreement does provide for the sharing of profits, so those same percentages will be used for losses: Able 50%; Baker 25%; and Charlie 25%. $25,000 of the loss is subtracted from Able ’s account, leaving a balance of $75,000. $12,500 is subtracted from Baker’s account, leaving a balance of $7,500. And $12,500 is subtracted from Charlie ’s account, leaving a balance of -$2,500. Partners are entitled to a settlement of their accounts upon winding up. If the balance in the account is negative, the partner must pay that amount. If the balance is positive, the partner is entitled to receive that amount. RUPA § 807(b). Thus, Able is entitled to receive $75,000; Baker is entitled to receive $7,500; and Charlie must pay $2,500. Once those payments are made, the balance should be $0, and the partnership is terminated. 17 Question 11 No one is liable under Rule 10b-5 for trading on material, nonpublic information unless there is a breach of fiduciary duty. Chiarella. Absent a breach of fiduciary duty, trading on nonpublic information does not constitute fraud. But any duty of confidentiality is sufficient; it does not necessarily have to be to the company whose stock is traded. O’Hagan. Debra clearly owes no fiduciary duty to Magna or SlowCopy. She has absolutely no relationship with either of those companies. Debra also owes no duty of confidentiality to Larry. She did not promise to keep the information secret and there ’s no evidence of a history of sharing confidences between the two of them so neither Rule 10b5-2(b)(1) or (b)(2) apply. She’s not a family member of Larry, so Rule 10b5-2(b)(3) also does not apply. She might, however, be liable as a tippee of Larry. Larry, as an employee of SlowCopy, owes it a fiduciary duty. In addition, because of SlowCopy’s contractual relationship with Magna and its promise of confidentiality, SlowCopy is a temporary insider as defined in fn. 14 of Dirks. Because of that, SlowCopy and Larry owe a duty of confidentiality directly to Magna. Dirks says that a tippee can be liable if two requirements are met: (1) the tipper breached a fiduciary duty; and (2) the tippee knew or should have known that the tipper was breaching a fiduciary duty. A tipper such as Larry breaches a fiduciary duty within the meaning of Dirks only if he provides the information for personal gain. Larry received no direct gain of any kind in providing the information to Debra. However, Dirks says that a gift of confidential information to a friend or family member can be a personal gain. Larry gave the information to Debra as a favor to her dad, his long-time friend. Although Larry didn’t intend for the father to trade on that information, he did intend to provide a benefit to him. That may be sufficient under Dirks. 18 The second requirement is that Debra must know or should have known of the breach of duty. Debra knew that Larry ’s information was nonpublic and came from Magna. She also knew that Larry was not supposed to disclose the information. However, to know that Larry breached a duty in the Dirks sense, she must also know that he did it for personal gain. Assuming that the gift to the father is sufficient personal gain, that requirement is probably met because Larry told her exactly why he was giving her the infor mation.