Harrison Bergeron, Title VII and the ADA

advertisement

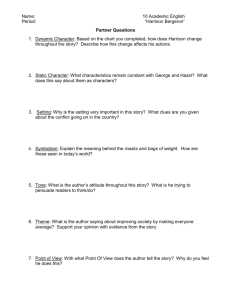

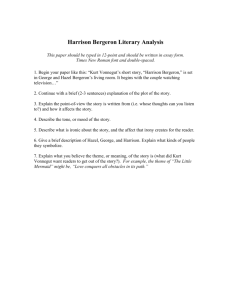

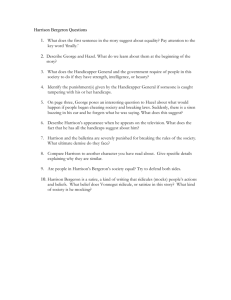

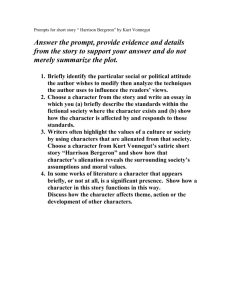

Harrison Bergeron1, Title VII and the ADA (or Science Fiction and the Law) “THE YEAR WAS 2081, and everybody was finally equal.” -- Kurt Vonnegut, from “Harrison Bergeron” In October, 1961, acclaimed American author Kurt Vonnegut first published his short story “Harrison Bergeron”. The story is just under 2200 words but has had a substantial impact on American legal and political thought. The story arrived as a warning, 3 short years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its natural expansion into the workplace decades later with the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act; all disallowing discrimination based of race, sex, age, disability, religion, or national origin. Vonnegut’s story is about America following the 211th, 212th, and 213th amendments to the United States Constitution. The purpose of the Amendments was to make all Americans equal. The Declaration of Independence asserted that all men are created equal. It became the job of the Handicapper General to see to it that all Americans stayed that way. So as to maintain equality, the Handicapper General’s office engaged in elaborate and personalized “handicaps”: the beautiful wore progressively uglier masks, the strong wore weights, and the intelligent wore distracting earpieces. These handicaps are enforced with prison sentences and fines, backed by the guns of the “H-G men”. Harrison is the 14 year old son of George and Hazel Bergeron. He was taken away from his home under the pretense of attempting to overthrow the If you have not read it, I implore you to first read the story before advancing through this paper. It can be found in its entirely online in dozens of places with a simple search engine. 1 government, and fitted with enormous handicaps, as following his eventual escape he is announced as being, “a genius and an athlete” as well as being underhandicapped despite wearing a mask, a distracting earpiece and the most weight ever assigned. The story ends with Harrison escaping prison and breaking into a local ballet, where he removes his handicaps as well as those of the musicians and dancers. He gives a short speech and provides a display of his extraordinary abilities as the musicians play to their fullest ability while the dancers dance unhindered by weights and masks. The Handicapper General arrives and executes Harrison on site, ordering the other members to replace their handicaps or face similar punishment. This entire ordeal is witnessed on television by Harrison’s parents, who quickly lose track of the event, either through the inattention of Hazel (who is of the new “average” intelligence) or through the loud, distracting noises blared into the ears of George, who is capable of above average thought. In 1964, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act was enacted to end discrimination in the workplace. More accurately worded, it was intended to level treatment in the workplace: to make everyone equal. Most claims are filed with a federal agency, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which serves as a modern Handicapper General’s office, before moving into the court system. The introductory subsection of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(a) aptly summarizes the mission of Title VII: It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer-- 2 (1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; or (2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or applicants for employment in any way which would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee, because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Prior to 1964, employment discrimination was perfectly legal. It was done for multiple purposes. Some employment discrimination was simply arbitrary racism or sexism. Other employment discrimination served a business purpose. Perhaps a company did not prefer to hire minorities due to the prejudices of customers, or did not hire women so as to prevent the necessary breaks that come from a pregnancy. Title VII claims to address these concerns with 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(e)(1), which states that an employer can discriminate in the event, “where religion, sex, or national origin is a bona fide occupational qualification reasonably necessary to the normal operation of that particular business or enterprise.” This is often referred to as the BFOQ defense. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court neuters this very important exception in UAW v. Johnson Controls, Inc. 499 U.S. 187 (1991). Johnson Controls Inc. was a battery manufacturing company. Aware of the threat faced by a fetus exposed to the lead levels involved in making batteries, the company issued warnings to all women, saying that they should avoid working in certain positions if they are at risk of becoming pregnant. The company shifted its policy to one that 3 excluded all women from working in positions that exposed them to lead after several employees became pregnant and tested with critical levels of lead in their bloodstream according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Stating that, “…the absence of a malevolent motive does not convert a facially discriminatory policy into a neutral policy with a discriminatory effect.” Id., the Court disallowed the threat to an unborn fetus as being enough to necessitate being male as a bonafide occupational qualification. With Johnson Controls Inc. as precedent, the BFOQ defense has been consistently upheld in only the most narrow of circumstances. Neither preferences of customers, workers, or and effort to prevent lawsuits is enough to qualify as a BFOQ defense. Much of the problem we face with Title VII, and the Americans with Disabilities Act is America’s love affair with the conflicting terms liberty and equality. In order to preserve equality, we must sacrifice liberty, as seen by the oppressive rules of antidiscrimation laws. Rather than accepting this fact and openly balancing liberty and equality, America lives under the fanciful illusion that the two work hand in hand rather than being at odds with each other. Title VII is a clear affront to liberty: by compelling owners of private businesses to hire and fire according to systems beyond their own design they lose the right to make their own decisions and utilize their rightfully earned property and resources as they see fit. However, if you take two equally qualified applicants and compel an employer to hire or fire on factors beyond those an employer may usually make judgments on (even if discriminatory) there is little actual active harm to the business. There may certainly be passive harm in compelling an employer to 4 make decisions that that will cause the business harm, but you aren’t asking the employer to actively contribute to his own weakness in the market. A few examples of this passive harm may be seen in disallowing an employer to hire only white workers when he knows his clientele has its own prejudices and may not go to a business with minority employees. Customer preference does not fall under a BFOQ defense. Another may be the employer who is forced to hire women knowing that a percentage of them will require prolonged periods of time off or inefficiency in work when they become pregnant. His nondiscriminatory hiring harms the employer here, but he isn’t required to become actively complicit in it. Finally, and most pervasively are the symbolic and unintended consequences of allowing such encroachment upon liberty. The creep effect, commonly known as the slippery slope effect is an often ridiculed and ignored, but even more often correct defense to assaults on liberty. If a person does not resist encroachment, he hastens his own demise. As Edmund Burke said, "All that's necessary for the forces of evil to win in the world is for enough good men to do nothing.” The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 is the natural expansion of antidiscrimination law begun with Title VII and made subject to the democratic process. Once the door had been opened to give government the power to dictate the hiring practices of private businesses, it then only became a matter of how wide the net could be cast to capture as many people as possible under a protected class. This is seen with additional acts widening Title VII protections as well as the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 or the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967. 5 Whereas Title VII disallowed discrimination on account of sex and race, these additional acts added age, disabled status (real and perceived disability), veteran status, religion, and national origin. To date, sexual orientation is not a protected class, but as the acts are subject to the democratic process, it can be expected that just as new disabilities fall under ADA protections, so too shall sexual orientation fall under Title VII protections. Having already accepted the notion of allowing for protected classes to promote equality, the lack of protections to homosexuals, transsexuals, ect is doubly offensive. To disallow them protected class status is to effectively borrow from George Orwell’s Animal Farm in stating that, “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.” In effect, we are not truly equal; rather, only those a democratic majority accepts are to be treated equal. Where the ADA separates from Title VII to create a more perfect tyranny is in making the employer an active participant in the injustice perpetrated against him. Now, not only does he have the Title VII requirement to disregard discriminating due to the disability of an applicant or employee, he must also make accommodations for the employee at his own expense. A common theme throughout the ADA is that the employer is expected to provide “reasonable accommodations”. However, like with Title VII’s exception for the BFOQ, the ADA claims that a business must not provide the kind of accommodation that would cause an “undue hardship” upon the employer. Often though, the courts can consider very expensive accommodations “reasonable”. There is very little reliability as to what a court qualifies as “reasonable”. In some circumstances, courts has demanded disabled employees be 6 provided jobs over more qualified in employees because the job itself would be the only one the employee is now capable of. In Smith v. Midland Brake, Inc., 180 F.3d 1154, (10th Cir. 1999), a worker was injured on the job and sued successfully when his employers would not reassign him over a more qualified employee by putting him into another department. Yet, in Vande Zande v. State of Wisconsin, 44 F.3d 538 (7th Cir. 1995) the court said that the employee must show the benefit of the accommodation is proportionate to the cost to the employer. Title VII also created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The purpose of the EEOC is to exist as the enforcement arm of these antidiscrimination laws. The EEOC works as a legal gatekeeper and prosecutorial middleman. Charges leveled by employees against employers involving the ADA, Title VII, ect, must first begin as complaints to the EEOC. In the event the EEOC does not find discrimination, they will allow the case to go forward, but will not provide their resources to help advance the litigation. This limits equality again by allowing only those “popular” disabilities or subject classes to be the ones to receive protection. Now let us return to the connection between these antidiscrimination acts and Harrison Bergeron. The intent of the 211th, 212th, and 213th amendments to the Constitution were designed to make everyone equal. “They weren't only equal before God and the law. They were equal every which way.” Previous to these acts it could be argued that everyone was equal before the law. There are no protected classes in a courtroom. All groups have equal access to the courts. But now with the ADA’s requirement for “reasonable accommodation”, the disabled man is equal with the able in the workplace. However, when that equality comes at the expense of the 7 able; the disabled man, rather than finding his productive place in society, becomes a destructive force, as he must harm another person to raise his status and abilities. In Harrison Bergeron, this equality was not only due to the Constitutional amendments, but also, “…the unceasing vigilance of agents of the United States Handicapper General.” The EEOC has a host of agents managing its administration. It is run by 5 politically appointed commissioners, as well as a General Counsel. The vigilance in prosecuting violations of federal antidiscrimination laws has been known to fluxuate wildly with the political makeup of the commission. This demonstrates the danger in allowing others to decide who is equal, rather than for things to progress in a natural state. If you lift a man temporarily, you only succeed in ensuring that he falls from a greater height. Subjecting antidiscrimination laws and the people that fall under them to the democratic process has and will certainly continue to cause angst and a desire to increase those that fall under special protection. At one point, Harrison’s mother, Hazel Bergeron, attempts to ease her exhausted husband’s pain by asking him to relax his weights: "If I tried to get away with it," said George, "then other people'd get away with it-and pretty soon we'd be right back to the dark ages again, with everybody competing against everybody else. You wouldn't like that, would you?" "I'd hate it," said Hazel. When externalities can be imposed that will level the playing field, those below that level will find it unacceptable to be there for any reason at all. Whether it is by making the weak stronger or making the strong weaker is irrelevant when concepts of fairness and equality are concerned. In Sway: The Irresistible Pull of Irrational 8 Behavior, by Ori and Rom Brafman, they describe an experiment where subjects are offered a choice between receiving a sum of money identical to the other people in their group, or twice that sum of money, but the members of the group get more than the test subject. In the interests of fairness (or perhaps envy), the test subjects overwhelmingly chose the smaller sum: it was equal, after all. The push for equality actively through the law takes us into the idea of making people better and denying nature. “Not only were the laws of the land abandoned, but the law of gravity and the laws of motion as well.” Some people are naturally stronger, smarter, and more resistant to disease, ect. Vonnegut brings us to this bleak dystopia where we fought the laws of nature, but doesn’t really address the unintended consequences of that world. On January 17th, 2001, Professional Golfer Casey Martin’s attorney argued before the Supreme Court that the ADA demanded that the Professional Golf Association Tour allow him to use a golf cart during their Tournaments. Martin had a documented circulatory disorder. This prevented him from being able to walk the necessary 18-hole course as the other golfers do. The PGA Tour argued that walking the course was a necessary rule of the game, as fatigue takes a mental and physical impact upon the players. Backing this assertion were several professional golfers. The Court did not accept this argument. Justice John Stevens wrote that walking was not an indispensible rule of golf, and that shot-making is the sole aspect of the game. As a result, the PGA Tour was required under the Americans with Disabilities Act to provide reasonable 9 accommodations. In this case that meant Casey Martin would be allowed to use his golf cart. In his dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia cited Harrison Bergeron, and stated that the ADA: [meant] that everyone gets to play by individualized rules which will assure that no one's lack of ability (or at least no one's lack of ability so pronounced that it amounts to a disability) will be a handicap. The year was 2001, and "everybody was finally equal." K. Vonnegut, Harrison Bergeron Science Fiction is generally not afraid to address these issues. Classics such as 1984, Brave New World, or Fahrenheit 451 show us more dystopian futures. In The Forever War by Joseph Haldeman, the main character, William Mandella returns home after a few months of battling aliens in distant worlds. Due to time dilation, when he returns, it is decades in a future foreign to him where the law prevents his mother from getting necessary medical attention due to her advanced age in a society with rationed “universal healthcare”. Mandella, who was dissatisfied with military life and prepared to leave it, reenlists into the military for continued combat as he is disgusted with the world he has returned to, not unlike the culture shock of a prisoner being released after decades behind bars. Robert Heinlein, often referred to as the “Dean of Science Fiction” has legal themes throughout several of his books. In The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, a newcomer to the moon is nearly killed upon violation of local customs. A friendly local teaches him that legal matters are often handled by hiring a judge and jury. The parties agree upon a judge and money is offered at the scene of the “crime” to recruit passers-by as jurors: 10 "Why, I suppose I need a lawyer, too." "I said 'counsel,' not 'lawyer.' Aren't any lawyers here." Again he seemed delighted. “I suppose counsel, if I elected to have one, would be of the same, uh, informal quality as the rest of these proceedings?" "Maybe, maybe not. I'm an informal sort of judge, that's all. Suit yourself." "Mm. I think I'll rely on your informality, your honor." The case ends with a fine to the accused (as opposed to being thrown into the airlock as he had been facing. The judge is paid the agreed upon rate as is the jury, with the judge fining one juror for falling asleep during the trial. In Stranger in a Strange Land, Heinlein addresses many novel legal ideas, one of which being the “Fair Witness”: He was lucky in being able to retain James Oliver Cavendish as his Fair Witness. While any Fair Witness would do, the prestige of Cavendish was such that a lawyer was hardly necessary-the old gentleman had testified many times before the High Court of the Federation and it was said that the wills locked up in his head represented not billions but trillions. The Fair Witness was a specially trained person, sometimes quite expensive, who could be hired to accompany a person anytime a witness might be necessary. Considering the modern reliability problems with eyewitnesses, a specially trained and credible witness could be invaluable. A citizen of the Federation could demand a Fair Witness at any time when legal matters are involved. This could also cause a Fair Witness to be used as a shield when a person fears abuse by authorities. 11 The testimony of a reliable witness on the whether or not an event actually happened would be more powerful than that of an attorney. The Fair Witness had his limitations though. Following a simple and costly legal blunder: "Damn! Good Lord, Mr. Cavendish, why didn't you suggest it to me?" "Sir?" The old man drew himself up and his nostrils dilated. "It would not have been ethical. I am a Fair Witness, not a participant. My professional association would suspend me for much less. Surely you know that." Stranger in a Strange Land also is also replete with simple legal barbs. Swiping at a man’s exasperation at a “fantastic” assertion, its proponent responds, “Don’t use that word to a lawyer, he won’t understand you. Straining at gnats and swallowing camels is a required course in all law schools.” Shortly after, he claims that even hundreds of years into our future, "It is (the fifteenth century) to a lawyer. They still cite Blackwell, Code Napoleon, or even the laws of Justinian.” Considering that today’s law student still learns law in much the same way as the lawyers of America’s founding, this is a hard point to argue against. A modern law student sits at his desk into the late night learning property law by reading Pierson v. Post and other ancient cases from the Queen’s Bench, just as Jefferson, Hamilton, Henry or Adams read the very same cases late into the night by candlelight. Science Fiction is much more than simple-minded escapist literature. Well written sci-fi provides a blank pallet and an opportunity to explore ideas in a setting uncluttered by the compromised world we live in. Books like The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and Stranger in a Strange Land allow us to experiment with ideas like the Fair Witness, jury nullification, and voluntary, hired judges and juries. 12 Harrison Bergeron gave us a warning: equality mandated by the law and enforced by government agents does not strengthen the weak. Rather, they weaken the strong. That future is a bleak one that ends in degrading the species and the eventual extinction of man. To ignore the political and legal game theory of science fiction as being simple escapist fiction is to ignore a valuable learning tool to advance our legal and political future. 13