EECS 690

advertisement

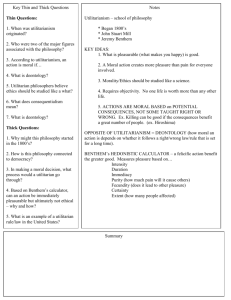

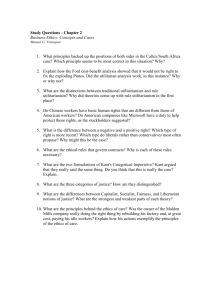

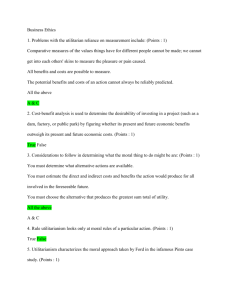

More objections to Utilitarianism A common objection dismissed: Objection: If there are 101 people, Util. says that 51 of them can do whatever they want to the other 50 as long as that makes them happy. No it doesn’t. (1) the unhappiness caused by deprivation must be factored in and (2) there are actions open that produce more happiness. Some Other common challenges: • Time (it takes too long to do a utilitarian calculus) – Util’s Response: Most decisions are easy and obvious. Many others are quickly enough made with brief thought, still others do allow time for extended thought. For those issues requiring time that is not available, we must hope our moral habits are good enough. • Inconsistency (utilitarianism is too situational) – Util’s Response: One theory’s inconsistency is another theory’s flexibility. To some extent we want our moral theories to be able to consider actions taken in different circumstances in different ways. • Uncertainty (shouldn’t we know if an action is moral when we do it?) – Util’s Response: It is true that some are better at anticipating consequences than others, however, nobody is excused from attempting to do so. People are often held responsible for outcomes they did not intend. The Util. says this is less a problem with utilitarianism than a problem with reality. Utilitarianism is too overriding/demanding • According to a strict interpretation of Util. you must give up any luxury possessions you have until the point of marginal utility (that is, give until just before it hurts). It may well be that morality demands this of us, but the extremity of this position gives many pause. • We will later read “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” by Peter Singer Utilitarianism is too impartial • Imagine a scenario in which a stranger is drowning, and so is your spouse. You only have time to reach one of them. • The solution to this dilemma seems obvious to most, but Util. provides no basis for the obvious answer. • Bernard Williams criticizes the Utilitarian in this situation for having “One thought too many”. Rule-Utilitarianism • In order to get out of objections like the time objection and the inconsistency objection, some Utilitarians have proposed that instead of doing only the action which generates the greatest utility, we ought to set up a system of rules that most of the time results in the best consequences. • This means that murder, rape, and pillage are always wrong, and it takes no time at all to be a good utilitarian—just follow the rules. • There are two main problems with this line of reasoning, contained on the next two slides. Rule-U devolves into Act-U • It seems that Rule-Utilitarianism best accomplishes its goals (to maximize wefare) if there is only one rule: “Maximize welfare” • In that case, rule-U is not even a separate thing from act-U. Utilitarianism is a poor basis for rules • Consider a person who cheats a bit on their taxes. They break the rules, and get the benefit of keeping a little extra money, and nothing bad whatsoever happens to anyone else (what’s a few hundred bucks to the US treasury?). This action results in the best consequences. • It appears that the way to optimize utility is not to have everybody follow the law, but instead to make sure that as many people break the law as possible without collapsing the system. • All rules appear to have this character in a Utilitarian system, and that’s really odd. A problem with aggregating utility • Utilizing a method of maximizing total utility in a fully utilitarian society leads to what is called “The reprehensible conclusion” which advocates as many people as possible living at the bare minimum. • Utilizing a method of maximizing average utility in a fully utilitarian society leads to what is called “The dastardly conclusion” in which a number of people sacrifice themselves to improve the average. The Reprehensible Conclusion: To maximize total, turn this: Into this? The Dastardly Conclusion: Maximize Average, Turn this: Into this? Study Questions • What is tempting about Rule-utilitarianism, and why does it ultimately not succeed? • Which of these objections if any, are strong enough to warrant abandoning utilitarianism? Why? • How might the utilitarian defend themselves against either the “reprehensible conclusion” or the “dastardly conslusion”?