Here - Columbia University Journal of Politics & Society

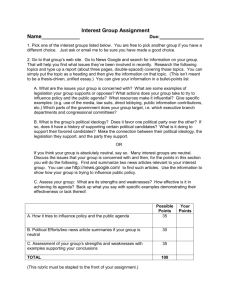

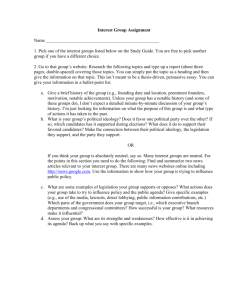

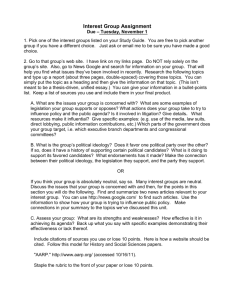

advertisement