Hardship Policies in Practice: A Comparative Study

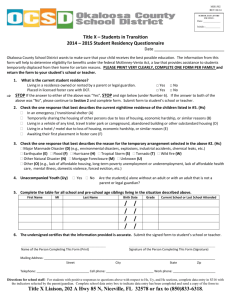

advertisement