Family

advertisement

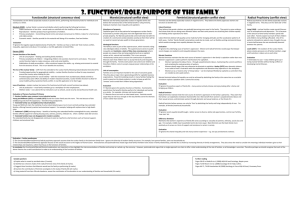

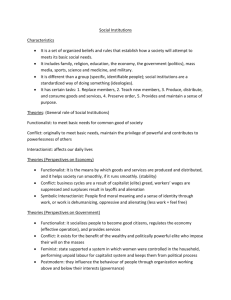

INTRODUCTION TO FAMILY & FAMILY IN THE CARIBBEAN • Haralambos, Michael et al. Sociology: Themes and Perspectives (Seventh Edition). HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. London (2008). • Mustapha, Nasser. Sociology for Caribbean Students (Second Edition). Ian Randle Publishers. Jamaica (2013). FAMILY DEFINED Family is an institution which can be defined as a “social group characterized by common residence, economic co-operation and reproduction. It includes adults of both sexes, at least two of whom maintain a socially approved sexual relationship, and one or more children, own or adopted, of the sexually cohabiting adults.” (Murdock 1949) FUNCTIONS OF THE FAMILY According to Murdock (1949), from his analysis of 250 societies, argues that the family possesses four universal functions: 1. Sexual gratification and companionship 2. Reproductive functions 3. Economic functions 4. Educational or Socialization functions Murdock, in his functionalist view, clarifies that the family does not perform these functions exclusively, however, it makes important contributions to them all and no other institution has yet been devised to match its efficiency in this regard. FAMILY VARIATIONS The structure of the family varies from society to society. For the purposes of this course, we will focus on the following variations: 1. The Nuclear Family 2. The Extended Family 3. The Vertically Extended Family (Consanguine) 4. The Horizontally Extended Family (Joint) 5. Single Parent Families 6. Sibling Families 7. Same-Sex Families 1. The Nuclear family Murdock (1949) describes the nuclear family as a “universal human form of social grouping” and the most” prevailing form of the family from which more complex forms are founded.” He says that “it exists as a distinct and strongly functional group in every known society.” It usually consists of two adults (a mother and a father) and their unmarried offspring. Members of the nuclear family may be related to one another by blood, adoption, marriage, or share a common residence. 2. The Extended Family The extended family consists of an addition to that of the nuclear family; in that it includes additional generations and relations. It may consists of two or more adults from different generations of a family who share a common household. Functional sociologists Bell and Vogel define the extended family as “any grouping broader than the nuclear family which is related by descent, marriage or adoption.” This type of family (apart from the parents and children) may include other relatives such as cousins, aunts, uncles and grandparents. 3. The Vertically Extended Family This is the first type of extended family or consanguine (blood) family where the family may comprise one, two or even three generations. An example of a consanguine family is the addition of the spouses’ parents to the household. 4. The Horizontally Extended Family The second type of extended family is the horizontally extended family (joint family). These are families that are extended as a result of the introduction of siblings’ spouses and children into the household. This type of family is more prevalent in North India or among members of the Indian Diaspora. 5. Single Parent Families This type of family structure is increasingly becoming visible across many societies. This is especially true in many Caribbean societies where there is a predominance of the matrifocal (female headed) households. Single parent families are emerging as a contradiction to Murdock’s definition of the ‘traditional family’ and raises some questions about its universality. Single parent families originate for numerous reasons; divorce, separation, desertion, abandonment, or as a result of death of a spouse. In modern times, career-oriented women have been seen to opt for the single parent lifestyle and to parent a child outside of marriage. 6. The Sibling Family This type of family (also found in the Caribbean) can be defined as a unity where an older brother or sister is the head of the household as a result of there being no parents present in the household. The absence of the parents from the household could be attributed to a number of reasons; domestic migration, international migration, death, incarceration, or desertion by parents. 7. Same-sex Families Many sociologists have attributed the differences in sexuality to the increasing diversity in society or what some sociologists will refer to as the ‘heteronorm’. Gay and lesbian households have become more commonplace as societies gradually embrace the legalization of same-sex marriages. Some homosexuals often look upon their households and even their friendship networks as being ‘chosen families’. (Weeks et al., 1999) This family type may also include children, who may bee from previous marriages, adopted or conceived through surrogate mothers by artificial insemination. CRITICISMS OF FUNCTIONALIST VIEW It is argued that other institutions could perform the functions listed that the family structure provides. Both Murdock and Parsons paint a very rosy picture of family life, presenting it as a harmonious and integrated institution and downplay conflict in the family. Feminists argue that their view on the roles of men and women are very traditional and old-fashioned. Feminists also raise the point that it ignores the way that women suffer from the sexual division of labour. Anthropological research has shown that there are some cultures which don’t appear to have ‘families’ – the Nayar for example: CASE STUDY: The Nayar in Kerala The study of the Nayar or Kerala in southern India by Gough (1959) bought into question the claim of the universality of family in Sociology. Gough in her study, described a society where pubescent Nayar girls were ritually married in the tali rite. However, the tali husband did not live with his wife and was under no obligation to have any contact with her whatsoever. The wife was relegated to only one duty; to attend his funeral and to mourn his death. A Nayar girl could have visiting husbands or sandbanham husbands. Men could have unlimited numbers of sandbanham wives, although women seem to have been limited to no more than twelve visiting husbands. CASE STUDY: The Nayar in Kerala (ctd.) Sandbanham relationships were unlike marriages in most societies in a number of ways: 1. They were not a lifelong union; either party could terminate the relationship at any time. 2. The husbands had no duty towards the offspring of their wives. It didn’t matter if the man was the biological parents, so long as someone claimed to be the child’s father, as he did not help to maintain or to socialize the child. 3. Husbands and wives did not form an economic unit. Instead, the economic unit consisted of a number of brothers and sisters, sisters’ children, and their daughters’ children. The eldest male was the leader of each group of kin. MARXIST PERSPECTIVE ON FAMILY Marxists argue that the family is not necessarily a haven of love and protection from the social world and the Functionalists advocate. Rather, they purport that this unit acts as an institution that is designed solely to meet the needs of the capitalist economic system. The institution of the family, therefore, is a system of power relations that reinforces and reflects the inequalities in society. Cooper (1972) argues that the family is an “ideological conditioning device in an exploitative society.” Marxists believe that the family has four major roles. The family is: 1. An agent of reproduction. 2. An agent of economic production. 3. An agent of female subjugation. 4. A prop to the capitalist system. CRITICISMS OF MARXIST VIEW Marxists tend to refer to the family in capitalist society without regard to possible variations in family life between social classes, ethnic groups, heterosexual and homosexual families, and single parent families. Morgan (1975) posits that both functionalist and Marxist approaches “presuppose a traditional model of the nuclear family where there is a married couple with children, where the husband is the breadwinner and where the wife stays at home to deal with the housework.” There is a general underestimation of the “extent of cruelty, violence, incest and neglect” within families. FEMINIST PERSPECTIVE ON FAMILY Like the Marxist view, the Feminist theory also provides a revolutionary view of the family. The main focus of Feminists is the negative effects of family life on women. They see the family as contributing to the exploitation of women in society. This exploitation is seen as wither a consequence of the power dynamic resulting in the subordination of women as well as the impact of the capitalist system. Okley (1974), in The Sociology of Housework, posits that women are exploited in contemporary society. Her main assertion is that the family is foremost a means of maintaining male dominance over women. This can only be reversed by a drastic change in the division of labour, the roles of the housewife, and the present family structures. CRITICISMS OF FEMINIST VIEW Feminist theory focuses too much on the role of women at the expense of the other family members. The concept of a patriarchal structure is too generalized. The implication that all women are exploited in the family is overstated. Morgan (1975) posits that both functionalist and Marxist approaches “presuppose a traditional model of the nuclear family where there is a married couple with children, where the husband is the breadwinner and where the wife stays at home to deal with the housework.” INTERACTIONIST PERSPECTIVE ON FAMILY Burgess (1926) proposed that the family can be viewed as “a unity of interacting personalities”; a little universe of communication in which roles and selves are shaped and each personality affects every other personality. The interaction of family members and intimate couples involves shared understandings of their situations. Wives and husbands have different styles of communication, and social class affects the expectations that spouses have of their marriage and of each other. Much contemporary family research deals with some type of role analysis; how gender role conceptions affect the definition of spousal roles, how the arrival of children change interaction patterns, how external and internal events affect role definitions, and how do role-specific variables affect the attitudes, self-conceptions and dispositions of family members. (Hunter, 1985) A large area of symbolic interactionist research deals with socialization. CRITICISMS OF INTERACTIONIST VIEW The interactionist perspective has been criticised for its over-emphasis upon the “individual" as the object of sociological study. Symbolic interactionism lacks in having macro theories of the family, although some argue that it makes up for this by having detailed understandings of family relations.