Seminar Presentation - National Humanities Center

advertisement

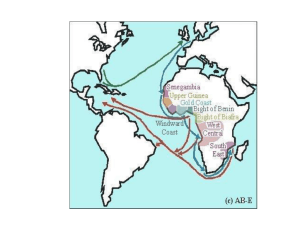

National Humanities Center The Great Migration; or Leaving my Troubles in Dixie Made possible through a grant from the Wachovia Foundation. The Great Migration; or Leaving my Troubles in Dixie Focus Questions What forces both pushed and pulled African Americans from the South in the Great Migration? How did African Americans imagine the North at the time of the Migration? What forces shaped the images and prominent themes that the Migration brought to African American literature? How were the realities African Americans encountered in "the Promised Land" of the North comparable to experiences they had undergone in the South? What roles did individuals, agencies, family, and business play in the movement north? How does an examination of westward migration and migration from rural to urban areas within the South broaden our understandings of the Great Migration? Trudier Harris National Humanities Center Fellow J. Carlyle Sitterson Professor Emerita Department of English University of North Carolina At Chapel Hill Summer Snow: Reflections from a Black Daughter of the South (2003) South of Tradition: Essays on African American Literature (2002) Saints, Sinners, Saviors: Strong Black Women in African American Literature (2001) The Power of the Porch: The Storyteller's Craft in Zora Neale Hurston, Gloria Naylor, and Randall Kenan (1996) National Humanities Center The Great Migration; or Leaving My Troubles in Dixie Session I Pushed and Pulled Out of the South How do you incorporate the Great Migration in your teaching? How was the myth of the North as a freer place for blacks created during slavery? African Americans escaping slavery ran north as they “followed the drinkin’ gourd.” The North Star became the title of Frederick Douglass’s newspaper. Harriet Tubman went south to the Egypt land of slavery and directed black people to freedom in the north. Authors of slave (freedom) narratives directed their texts to white Northerners whom they believed to be sympathetic to abolition. What did the North symbolize to those enslaved in the South? Freedom from the physical drudgery of slavery Freedom to abandon names imposed upon them by so-called masters Pay for physical labor Freedom of movement and association Out from under the slaveholder’s shadow The “Promised Land” of songs, poems, and tales What Prompted the Great Migration? Racial violence: “Between 1882 and 1927, an estimated 4,951 persons were lynched in the United States. Of that number, 3,513 were black and 76 of those were women.” Invention of the mechanical cotton picker Worn-out soil Natural disasters: failure of cotton crops in the 1910s, drought, boll weevil infestations Demand for labor in the North, spurred by World War I Younger blacks did not feel the same attachment to the soil that their ancestors felt. Tightening of immigration laws opened jobs for which blacks could qualify Traveling blues men, wayward husbands, relatives, and other visitors to the North who never returned Mobile, Ala. June 11, 1917 Dear Sir: Will you please send me the name of the society in Chicago that cares for colored emigrants who come north seeking employment sometime ago I saw the name of this society in the defender but of late it does not appear in the paper so I kindly as[k] you please try and get the name of this society and send the same to me at this city. New Orleans, La., April 30, 1917. Dear Sir: Seeing you ad in the defender I am writing you to please give me some information concerning positions- unskilled labor or hotel work, waiter, porter, bell boy, clothes cleaning and pressing. I am experienced in those things, especially in the hotel line. Am 27 years of age, good health – have a wife- wish you could give me information as I am not ready to come up at present. Would be thankful if you could arrange with some one who would forward transportation for me and wife. would be very glad to hear from you as soon as convenient. Thanking you in advance for interest shown me Palestine, Tex., Mar. 11th 1917 Sirs: this is somewhat a letter of information I am a colored boy aged 15 years old and I am talented for an artist and I am in search of some one will Cultivate my talent I have studied Cartooning therefore I am a Cartoonist and I intent to visit Chicago this summer and I want to keep in touch with your association and too from you knowledge can a Colored boy be an artist and make a white man’s salary up there I will tell you more and also send a fiew samples of my work when I rec an answer from you. Temple Texas, April 29, 1917. Mr. T. Arnold Hill, 3719 State St., Chicago, IL. Dear Sir: Being a reader of the Defender and young man seeking to better my conditions in the business world, I have decided to leave this State for North or West. I would like to get in touch with a person or firm that I might know where I can secure steady work. I would certainly appreciate any information you might be able to give. I finished the course in Blacksmithing and horseshoeing at Prairie View College this State and took special wood working in Hampton Instititute Hampton Va. Have been in practical business for sevaral years also I am specializing auto work. I am a married man a member of the church. Thanking you in advance for any favors am very truly Natchez, Miss., Sept 22-17. Mr. R.S. Abbott, Editor. Dear Sir: I thought that you might help me in Some way either personally or through your influence, is why I am worrying you for which I beg pardon. I am a married man having wife and mother to support, (I mention this in order to properly convey my plight) conditions here are not altogether good and living expenses growing while wages are small. My greatest desire is to leave for a better place but am unable to raise the money. I can write short stories all of which portray negro characters but no burlesque can also write poems, have a gift for cartooning but have never learned the technicalities of comic drawing. These thing will never profit me anything here in Natches. Would like to know if you could use one or two of my short stories in serial form in your great paper they are very interesting and would furnish good reading matter. By this means I could probably leave here in short and thus come in possession of better employment enabling me to take up my drawing which I like best. Kindly let me hear from you and if you cannot favor me could you refer me to any Negro publication buying fiction from their race. New Orleans, La., May 7, 1917. Gentleman: I read Defender every week and see so much good youre doing for the southern people & would like to know if you do the same for me as I am thinking of coming to Chicago about the first of June and wants a position. I have very fine references if needed. I am a widow of 28. No children, not a relative living and I can do first class work as house maid and dining room or care for invalid ladies. I am honest and neat and refined with a fairly good education. I would like a position where I could live on places because its very trying for a good girl to be out in a large city by self among strangers is why I would like a good home with good people. Trusting to hear from you. How did black people hear about the opportunities that were available in the North? Relatives “So many of my folks are leaving that I thought I’d go up and see whether or not they had made a mistake. I found thousands of old friends up there making more money than they’d ever made in their lives. I said to one woman in Chicago, “Well, Sister ––, I see you’re here.” “Yes, Brother, I’m here, thank the Lord.” “Do you find it any colder up here than it was in Mississippi?” “Did I understand you correctly to say cold? Honey, I mean it’s cold. It is some cold.” “But you expect to return, don’t you?” “Don’t play with me, chile. What am I going to return for? I should say not. Up here you see when I come out on the street I walk on nice smooth pavements. Down home I got to walk home through the mud. Up here at nights it don’t matter much about coming home from church. Down home on my street there ain’t a single lamp post. And say, honey, I got a bath tub!” How did black people hear about the opportunities that were available in the North? Churches Labor agents Pullman porters (Larry Tye, Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class, 2005) How did black people hear about the opportunities that were available in the North? Newspaper Reports To die from the bite of frost is far more glorious than at the hands of a mob. I beg you, my brother, to leave the benighted land. You are a free man. Show the world that you will not let false leaders lead you. Your neck has been in the yoke. Will you continue to keep it there because some “white folks’ nigger” wants you to? Leave for all quarters of the globe. Get out of the South. Your being there in the numbers in which you are gives the southern politician too strong a hold on your progress. . . . So much has been said through the white papers in the South about the members of the race freezing to death in the North. They freeze to death down South when they don’t take care of themselves. There is no reason for any human being staying in the Southland on this bugaboo handed out by the white press. If you can freeze to death in the North and be free, why freeze to death in the South and be a slave, where your mother, sister and daughter are raped and burned at the stake; where your father, brother and sons are treated with contempt and hung to a pole, riddled with bullets at the least mention that he does not like the way he is treated. Come North then, all you folks, both good and bad. If you don’t behave yourselves up here, the jails will certainly make you wish you had. For the hard-working man there is plenty of work if you really want it. The Defender says come. Patterns of Migration “The most interesting thing is how these people left. They were selling out everything they had or in a manner giving it away; selling their homes, mules, horses, cows, and everything about them but their trunks. All around in the country, people who were so old they could not very well get about were leaving. Some left with six to eight very small children and babies half clothed, no shoes on their feet, hungry, not anything to eat and not even a cent over their train fare. Some would go to the station and wait there three or four days for an agent who was carrying them on passes. Others of this city would go in clubs of fifty and a hundred at a time in order to get reduced rates. They usually left on Wednesday and Saturday nights. One Wednesday night I went to the station to see a friend of mine who was leaving. I could not get in the station, there were so many people turning like bees in a hive. Officers would go up and down the tracks trying to keep the people back. One old lady and man had gotten on the train. They were patting their feet and singing and a man standing nearby asked, ‘Uncle, where are you going?’ The old man replied, ‘Well son, I’m gwine to the promised land.’” --Account of migration fever reported in Emmett J. Scott’s Negro Migration During the War, 1920 One Way Ticket Langston Hughes I pick up my life And take it with me And I put it down in Chicago, Detroit, Buffalo, Scranton, Any place that is North and East— And not Dixie. I pick up my life And take it on the train To Los Angeles, Bakersfield, Seattle, Oakland, Salt Lake, Any place that is North and West— And not South. I am fed up With Jim Crow laws, People who are cruel And afraid, Who lynch and run, Who are scared of me And me of them. I pick up my life And take it away On a one-way ticket— Gone up North, Gone out West, Gone! Richard Wright, “The Ethics of Living Jim Crow,” 1937 Section IV Negroes who have lived South know the dread of being caught alone upon the streets in white neighborhoods after the sun has set. In such a simple situation as this the plight of the Negro in America is graphically symbolized. While white strangers may be in these neighborhoods trying to get home, they can pass unmolested. But the color of a Negro's skin makes him easily recognizable, makes him suspect, converts him into a defenseless target. Section I When I told the folks at home what had happened, they called me a fool. They told me that I must never again attempt to exceed my boundaries. When you are working for white folks, they said, you got to "stay in your place" if you want to keep working. I Richard Wright, “The Ethics of Living Jim Crow,” 1937 Section VIII One night, just as I was about to go home, I met one of the Negro maids. She lived in my direction, and we fell in to walk part of the way home together. As we passed the white nightwatchman, he slapped the maid on her buttock. I turned around amazed. The watchman looked at me with a long, hard, fixed under stare. Suddenly he pulled his gun, and asked: "Nigger, don't yuh like it?" I hesitated. "I asked yuh don't yuh like it?" he asked again, stepping forward. "Yes, sir," I mumbled. "Talk like it, then" "Oh, yes, sir!" I said with as much heartiness as I could muster. National Humanities Center The Great Migration; or Leaving My Troubles in Dixie Session II The Promised Land Alain Locke, “Enter the New Negro,” 1925 “So for generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being --a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be "kept down," or "in his place," or "helped up," to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden. The thinking Negro even has been induced to share this same general attitude, to focus his attention on controversial issues, to see himself in the distorted perspective of a social problem.” . . . “Recall how suddenly the Negro spirituals revealed themselves; suppressed for generations under the stereotypes of Wesleyan hymn harmony, secretive, halfashamed, until the courage of being natural brought them out--and behold, there was folk-music. Similarly the mind of the Negro seems suddenly to have slipped from under the tyranny of social intimidation and to be shaking off the psychology of imitation and implied inferiority. By shedding the old chrysalis of the Negro problem we are achieving something like a spiritual emancipation.” . . . “The day of "aunties," "uncles" and "mammies" is equally gone. Uncle Tom and Sambo have passed on, and even the "Colonel" and "George" play barnstorm roles from which they escape with relief when the public spotlight is off. The popular melodrama has about played itself out, and it is time to scrap the fictions, garret the bogeys and settle down to a realistic facing of facts.” Alain Locke, “Enter the New Negro,” 1925 “The fiction is that the life of the races is separate and increasingly so. The fact is that they have touched too closely at the unfavorable and too lightly at the favorable levels.” . . . “The particular significance in the reestablishment of contact between the more advanced and representative classes is that it promises to offset some of the unfavorable reactions of the past, or at least to re-surface race contacts somewhat for the future. Subtly the conditions that are moulding a New Negro are moulding a new American attitude.” . .. “Therefore the Negro today wishes to be known for what he is, even in his faults and shortcomings, and scorns a craven and precarious survival at the price of seeming to be what he is not. He resents being spoken for as a social ward or minor, even by his own, and to being regarded a chronic patient for the sociological clinic, the sick man of American Democracy. For the same reasons he himself is through with those social nostrums and panaceas, the so-called "solutions" of his "problem," with which he and the country have been so liberally dosed in the past. Religion, freedom, education, money--in turn, he has ardently hoped for and peculiarly trusted these things; he still believes in them, but not in blind trust that they alone will solve his life-problem.” Alain Locke, “Enter the New Negro,” 1925 “This deep feeling of race is at present the mainspring of Negro life. It seems to be the outcome of the reaction to proscription and prejudice; an attempt, fairly successful on the whole, to convert a defensive into an offensive position, a handicap into an incentive.” . . . “But fundamentally for the present the Negro is radical on race matters, conservative on others, in other words, a "forced radical," a social protestant rather than a genuine radical. Yet under further pressure and injustice iconoclastic thought and motives will inevitably increase.” . . . “Democracy itself is obstructed and stagnated to the extent that any of its channels are closed. Indeed they cannot be selectively closed. So the choice is not between one way for the Negro and another way for the rest, but between American institutions frustrated on the one hand and American ideals progressively fulfilled and realized on the other.” Alain Locke, “Enter the New Negro,” 1925 How would you have us, as we are? Or sinking heath the load we bear, Our eyes fixed forward on a star, Or gazing empty at despair? Rising or falling? Men or things? With dragging pace or footsteps fleet? Strong, willing sinews in your wings, Or tightening chains about your feet? --James Weldon’s Johnson’s “To America” . . . “Harlem, as we shall see, is the center of both these movements; she is the home of the Negro's "Zionism." The pulse of the Negro world has begun to beat in Harlem. A Negro newspaper carrying news material in English, French and Spanish, gathered from all quarters of America, the West Indies and Africa has maintained itself in Harlem for over five years. Two important magazines, both edited from New York, maintain their news and circulation consistently on a cosmopolitan scale. Under American auspices and backing, three pan-African congresses have been held abroad for the discussion of common interests, colonial questions and the future cooperative development of Africa.” Leslie Rogers, “People We Can Get Along Without, The Chicago Defender, July 9, 1921 Rudolph Fisher, “The City of Refuge,” 1925 Gillis set down his tan cardboard extension case and wiped his black, shining brow. Then slowly, spreadingly, he grinned at what he saw: Negroes at every turn; up and down Lenox Avenue, up and down 135th Street; big, lanky Negroes, short, squat Negroes; black ones, brown ones, yellow ones; men standing idle on the curb, women, bundle-laden, trudging reluctantly homeward, children rattle-trapping about the sidewalks; here and there a white face drifting along, but Negroes predominantly, overwhelmingly everywhere. There was assuredly no doubt of his whereabouts. This was Negro Harlem. . . . In Harlem, black was white. You had rights that could not be denied you; you had privileges, protected by law. And you had money. Everybody in Harlem had money. It was a land of plenty. Why, had not Mouse Uggam sent back as much as fifty dollars at a time to his people in Waxhaw? . . . “Done died an’ woke up in Heaven,” thought King Solomon, watching, fascinated; and after a while, as if the wonder of it were too great to believe simply by seeing, “Cullud policemans!” he said, half aloud; then repeated over and over, with greater and greater conviction, “Even got cullud policemans—even got cullud —” Rudolph Fisher, “The City of Refuge,” 1925 Uggam sought out Tom Edwards, once a Pullman porter, now prosperous proprietor of a cabaret, and told him: “ Chief, I got him: a baby jess in from the land o’cotton and so dumb he thinks ante bellum’s an old woman.” . . . An airshaft: cabbage and chitterlings cooking; liver and onions sizzling, sputtering; three player-pianos out-plunking each other; a man and a woman calling each other vile things; a sick, neglected baby wailing; a phonograph broadcasting blues; dishes clacking; a girl crying heartbrokenly; waste noises, waste odors of a score of families, seeking issue through a common channel; pollution from bottom to top — a sewer of sounds and smells. Rudolph Fisher, “The City of Refuge,” 1925 “Stealin’? ’T wouldn’t be stealin’. Stealin’ ’s what that damn monkey-chaser tried to do from you. This would be doin’ Tony a favor an’ gettin’ y’self out o’ the barrel. What’s the holdback?” “What make you keep callin’ him monkey-chaser?” “West Indian. That’s another thing. Any time y’ can knife a monk, do it. They’s too damn many of ’em here. They’re an achin’ pain.” “Jess de way white folks feels ’bout niggers.” . . . King Solomon was in a position to help him now, same as he had helped King Solomon. He would leave a dozen packages of the medicine — just small envelopes that could all be carried in a coat pocket — with King Solomon every day. Then he could simply send his customers to King Solomon at Tony’s store. They’d make some trifling purchase, slip him a certain coupon which Uggam had given them, and King Solomon would wrap the little envelope of medicine with their purchase.. Rudolph Fisher, “The City of Refuge,” 1925 “Look, Mouse!” he whispered. “Look a yonder!” “Look at what?” “Dog-gone if it ain’ de self-same girl?” Wha’ d’ ye mean, self-same girl!” “Over yonder, wi’ de green stockin’s. Dass de gal made me knock over dem apples fust day I come to town. ’Member? Been wishin’ I could see her ev’y sence.” “What for?” Uggam wondered. King Solomon grew confidential. “Ain’ but two things in dis world, Mouse, I really wants. One is to be a policeman. Been wantin’ dat ev’y sence I seen dat cullud traffic cop dat day. Other is to get myse’f a gal lak dat one over yonder!” . . . “Didn’t I just see him sell you something?” “Guess you did. We happened to be sittin’ here at the same table and got to talkin’. After a while I says I can’t seem to sleep nights, so he offers me sump’n he says ‘ll make me sleep, all right. I don’t know what it is., but he says he uses it himself an’ I offers to pay him what it cost him. That’s how I come to take it. Guess he’s got more in his pocket there now.” Rudolph Fisher, “The City of Refuge,” 1925 “Are you coming without trouble?” Mouse Uggam, his friend. Harlem. Land of plenty. City of refuge — city of refuge. If you live long enough ⎯ Consciousness of what was happening between the pair across the room suddenly broke through Gillis’s daze like flame through smoke. The man was trying to kiss the girl and she was resisting. Gillis jumped up. The detective, taking the act for an attempt to escape, jumped with him and was quick enough to intercept him. The second officer came at once to his partner’s aid, blowing his whistle several times as he came. . . . Downing one of the detectives a third time and turning to grapple again with the other, Gillis found himself face to face with a uniformed black policeman. He stopped as if stunned. For a moment he simply stared. Into his mind swept his own words, like a forgotten song suddenly recalled: “Cullud policemans!” Gwendolyn Brooks, “of De Witt Williams on his way to Lincoln Cemetery,” 1945 He was born in Alabama. He was bred in Illinois. He was nothing but a Plain black boy. Don’t forget the Dance Halls— Warwick and Savoy, Where he picked his women, where He drank his liquid joy. Swing low swing low sweet sweet chariot. Nothing but a plain black boy. Born in Alabama. Bred in Illinois. He was nothing but a Plain black boy. Drive him past the Pool Hall. Drive him past the Show. Blind within his casket, But maybe he will know. Down through Forty-seventh Street: Underneath the L, And Northwest Corner, Prairie, That he loved so well. Swing low swing low sweet sweet chariot. Nothing but a plain black boy. Alice Walker, “Roselily,” 1967 She dreams; dragging herself across the world. A small girl in her mother’s white robe and veil, knee raised waist high through a bowl of quicksand soup. The man who stands beside her is against this standing on the front porch of her house, being married to the sound of cars whizzing by on highway 61. . . . She thinks of ropes, chains, handcuffs, his religion. His place of worship. Where she will be required to sit apart with covered head. In Chicago, a word she hears when thinking of smoke, from his description of what a cinder was, which they never had in Panther Burn. She sees hovering over the heads of the clean neighbors in her front yard black specks falling, clinging, from the sky. But in Chicago. Respect, a chance to build. Her children at last from underneath the detrimental wheel. A chance to be on top. What a relief, she thinks. What a vision, a view, from up so high. Alice Walker, “Roselily,” 1967 She thinks of the man who will be her husband, feels shut away from him because of the stiff severity of his plain black suit. His religion. A lifetime of black and white. Of veils. Covered head. It is as if her children are already gone from her. Not dead, but exalted on a pedestal, a stalk that has no roots. She wonders how to make new roots. It is beyond her. She wonders what one does with memories in a brand-new life. This had seemed easy, until she thought of it. “The reasons why . . . the people who” . . . she thinks, and does not wonder where the thought is from. . .. In the city. He sees her in a new way. This she knows, and is grateful. But is it new enough? She cannot always be a bride and virgin, wearing robes and veil. Even now her body itches to be free of satin and voile, organdy and lily of the valley. Memories crash against her. Memories of being bare to the sun. She wonders what it will be like. Not to have to go to a job. Not to work in a sewing plant. Not to worry about learning to sew straight seams in workingmen’s overalls, jeans, and dress pants. Her place will be in the home, he has said, repeatedly, promising her rest she had prayed for. But now she wonders. When she is rested, what will she do? They will make babies ⎯ she thinks practically about her fine brown body, his strong black one. They will be inevitable. Her hands will be full. Full of what? Babies. She is not comforted. Alice Walker, “Roselily,” 1967 Impatient to see the South Side, where they would live and build and be respectable and respected and free. Her husband would free her. A romantic hush. Proposal. Promises. A new life! Respectable, reclaimed, renewed. Free! In robe and veil. . . . She blinks her eyes. Remembers she is finally being married, like other girls. Like other girls, women? Something strains upward behind her eyes. She thinks of the something as a rat trapped, cornered, scurrying to and fro in her head, peering through the windows of her eyes. She wants to live for once. But doesn’t know quite what that means. Wonders if she has ever done it. If she ever will. . . . Her husband’s hand is like the clasp of an iron gate. People congratulate. Her children press against her. Alice Walker, “Roselily,” 1967 She thinks how it will be later in the night in the silvery gray car. How they will spin through the darkness of Mississippi and in the morning be in Chicago, Illinois. She thinks of Lincoln, the president. That is all she knows about the place. She feels ignorant, wrong, backward. She presses her worried fingers into his palm. He is standing in front of her. In the crush of well-wishing people, he does not look back. Final Slide . Thank you.