Games of Ancient Rome - CLIO History Journal

advertisement

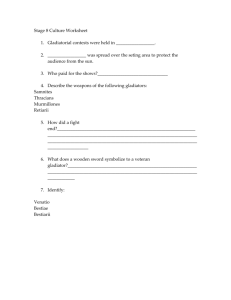

Games of Ancient Rome "We who are about to die salute you!” Contents Origins of games Height of popularity Culture of Violence Gladiators and associated roles Amphitheatres and arenas Decline in popularity Map of Roman Republic Italy and its colonies Origins of Games First gladiatorial contest took place at Rome in 264BC. The original Gladiatorial contest was called a munus meaning ‘a duty’ or munera meaning ‘duties’. They originated as funeral games for families to pay ‘duty’ to the dead. Gladiatorial games gradually lost their exclusive connection with the funerals of individuals and became an important part of the public spectacles staged by politicians and emperors and became known as ludi (games). The popularity of gladiatorial games is indicated by the large number of wall paintings and mosaics depicting gladiators. Floor mosaic in a Roman villa in Nennig Mosaic found in Pompeii Why do the people get angry at gladiators and so nastily that they think it an injury because [the gladiators] do not perish willingly? [The people] believe that they have been scorned and in facial expression, gesture, and passion are turned from a spectator into an opponent. - Seneca ...we despise gladiators if they are willing to do anything to preserve their life; we favour them, if they give evidence of their contempt for it. - Seneca - Height of popularity Gladiatorial contests were highly popular during the late Roman Republic (80-30 BCE) and throughout the Roman Empire (30 BCE- 350 CE) Often used by individuals for self-promotion. Games were often used to please the population and to gain support for election to public office. Ownership of gladiators or a gladiator school gave muscle and flair to Roman politics. “Generous” Imperial ludi (games) might cost no less than 180,000 denarii ($3.6 million). Culture of Violence Attending gladiatorial contests in the amphitheatre was an essential part of being a Roman. Rome was a warrior state that had achieved its large empire by military violence: Italian Wars, Samnite Wars, Pyrrhic Wars, Punic Wars, Wars/Invasion in Gaul, Iberia, Britain etc etc...the list goes on...Not to mention that Rome was founded on the back of Roman rebellion and violence against the Etruscans AND it collapsed into civil war thirteen times between 133-30BCE! War was a high-stakes proposition, both for the Romans and their opponents. Thousands of Roman soldiers died in Italy and abroad in countless battles. Roman treatment of the enemy could be very harsh, sometimes even involving the slaughter of civilians. ‘In Spain, during the second Punic War, Scipio Africanus the Elder attacked the city of Iliturgi, which had gone over to the enemy, and his soldiers killed all armed and unarmed citizens alike, including women and infants’ (Livy – Roman Historian) In Rome, prisoners of war were often executed in public. In order to ensure military discipline, Roman soldiers could be very harsh on their own kind, as is evident in the practice of decimation, in which one soldier out of every ten guilty of cowardice or dereliction of duty was chosen by lot to be bludgeoned to death by his fellow soldiers. Gladiators and associated roles There are many different types of Gladiator, however listed below are some well known types that were popular: Equites (cavalryman) – lance and short sword Thrax (Thracians) – curved swords, curve rimmed helmet Retiarri – Fought with net, trident and dagger Bestiarri – Beast/animal fighter Venator (hunter) – specialised in live animal hunts and entertainment (circus performers) Lanista (owner/trainer) – owned and traded in slaves which were trained as Gladiators Editor (producer) – Sponsor who helped finance spectacles Mosaic showing a retiarius (net-fighter) named Kalendio fighting a secutor named Astyanax’ In the bottom image, the secutor is covered in the retiarius's net, but doesn't seem to be hindered. In the later image, Kalendio is on the ground, wounded, and raises his dagger to surrender. The arena employees await his fate from the editor, not pictured. The inscription above it shows the sign for "null" and the name of Kalendio, implying that he was killed. A retiarius gladiator stabs at his secutor opponent with his trident. Mosaic from the villa at Nennig. The Zliten mosaic is a Roman floor mosaic from about the 2nd century CE (between 100-199), found in the town of Zliten in Libya. The mosaic depicts different types of games: 1. Referees/musicians and combat between equites 2. a retiarius and secutor, a Thraex and murmillo, a hoplomachus and murmillo in battle 3. Venationes (animal hunts) 4. Damnatio ad bestias (condemnation to beasts) Zliten mosaic (full version) You can see the images from the previous slide around the edge of the mosaic. Much of the mosaic is damaged however it does give us (as historians) an insight into the attitude of Romans about Gladiatorial combat and games. They enjoyed it so much that they honoured their sporting heroes in mosaics throughout their homes. Amphitheatres and arenas There are numerous examples of Roman arenas and amphitheatres most famously the Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheatre) in Rome. The Colosseum represents an important aspect of Roman society – public entertainment and more importantly Imperial respect for the power of the public. The Colosseum is built to entertain the people and promote Imperial leadership. However, there are many arenas, larage and small, throughout the Roman Empire. The amphitheatre was a microcosm of Roman society. The seating arrangements reflected the stratification of Roman society: the seating was divided between Senators, the wealthy and poor, slaves and freedmen. Of course the Emperor had his own seating area. The order of the day – The Colosseum Morning – Wild Animal Hunts also known as Venationes Midday (noon) – Public Executions Afternoon –Gladiatorial Contests In the noon time event, condemned criminals fought each other as if they were gladiators. Each combat was literally a "sudden death" contest, the winner of which had to fight other criminals until he himself was killed. In this way the condemned executed each other. What happened to the ultimate winner is not known; perhaps he was pardoned or at least allowed to live to fight another day. Seneca took a practical and judicial view of these contests: “[The purpose of executing criminals in public] is that they serve as a warning to all, and because in life they did not wish to be useful citizens, certainly the state benefits by their death.” An interesting case study: Riot at Pompeii 59CE “About this time [AD 59] there was a serious fight between the inhabitants of two Roman settlements, Nuceria and Pompeii. It arose out of a trifling incident at a gladiatorial show....During an exchange of taunts— characteristic of these disorderly country towns—abuse led to stone-throwing, and then swords were drawn. The people of Pompeii, where the show was held, came off best. Many wounded and mutilated Nucerians were taken to the capital. Many bereavements, too, were suffered by parents and children. The emperor instructed the senate to investigate the affair. The senate passed it to the consuls. When they reported back, the senate debarred Pompeii from holding any similar gathering for ten years. Illegal associations in the town were dissolved; and the sponsor of the show and his fellowinstigators of the disorders were exiled.” - Tacitus - Riot at Pompeii The riot at Pompeii indicates the passion people had for games. However, it is unlikely that the riot was provoked simply by the games that day. During the Social War (91-88 BCE), a century and a half earlier, Rome's Italian allies had fought to acquire the benefits of citizenship. Pompeii joined the revolt but fell to Sulla (Dictator), who settled a colony of legionary veterans there. The amphitheatre, itself, was constructed about 70 BCE for the benefit of these new colonists, both because of its association with the Roman military and as a monumental reminder of their dominance over the local Samnite population. Nuceria had not rebelled and subsequently was awarded territory confiscated from a neighbouring town that had been destroyed during the fighting. Less than two years before the riot, Nero settled a veteran colony at Nuceria (Annals), which no doubt inflamed old resentments, especially if assigned lands were disputed by the Pompeians. Decline in popularity Started to become a financial burden on the Empire and Imperial purse. The spreading of Christianity throughout the Empire (encouraged by Emperor Constantine I Edict of Milan in 313 promoting religious tolerance) changed the populations attitude to public killings and pagan human sacrifice. According to Christians at the time the combats were murder, their witnessing spiritually and morally harmful and the gladiator an instrument of pagan human sacrifice. However, it was not until 4th and 5th Century CE that ludi and munus were made illegal and were phased out, at least in the Western Roman Empire.