What are sedimentary rocks?

advertisement

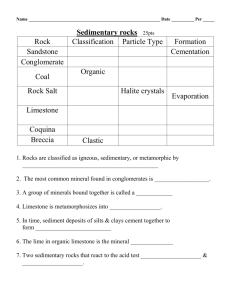

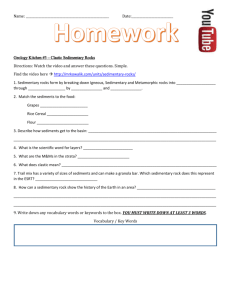

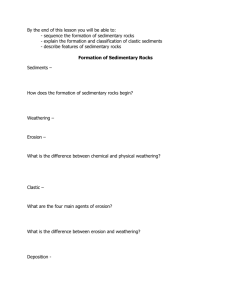

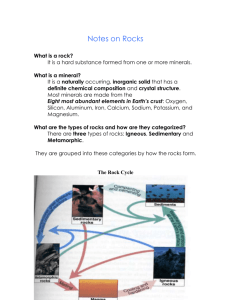

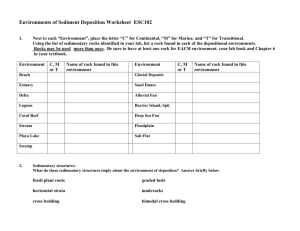

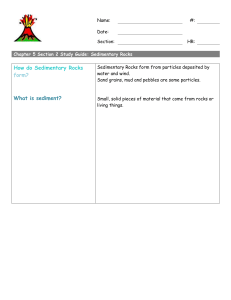

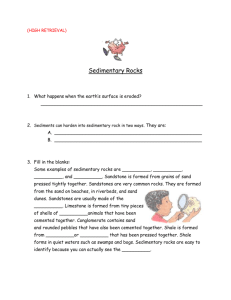

Lecture 5 Sedimentary Rocks What are sedimentary rocks? Sedimentary environments -- where are sedimentary rocks formed? How do sediments turn into rocks? Types of sedimentary rocks Clastic sedimentary rocks Chemical sedimentary rocks Features of sedimentary rocks What are sedimentary rocks? Sedimentary rocks are rock particles and mineral grains (sediments) deposited in a fluid (water or air) and subsequently transformed to rocks ("lithified"). They typically occur in layers (strata) separated by bedding planes or different composition. Sedimentary rocks consist of 75% of all rocks exposed at Earth's surface. Many of you will work more with sedimentary rocks than with the other rock types. Grand Canyon Limestone strata, Grenoble, France Sedimentary environments -- where are sedimentary rocks formed? Sedimentary rocks are formed in a variety of environment where sediment accumulates. Sedimentary environments typically are in the areas of low elevation at the surface, which can be divided into continental, shoreline, and marine environments. Each environment is characterized by certain physical, chemical, and biological conditions, thus sedimentary rocks hold clues to ancient environments and Earth history. Desert sand forms sandstone. (Right), Native Americans built a village under this ledge at Mesa Verde, Colorado, from sandstone blocks. (Stephen Marshak) Mud forms shale. This shale bed has split into thin sheets. (Stephen Marshak) Lithification -- How do sediments turn into rocks? The main processes of lithification are compaction, cementation, and crystallization. compaction: the pore space is reduced by pressure. cementation: the filling of the pore space by binding agents (calcite, quartz, iron oxide) crystallization: particularly in chemical sedimentary rocks. Types of sedimentary rocks Sedimentary rocks can be divided into two major types: clastic and chemical. The term clastic (Greek: "broken") describes the broken and worn particles of rock and minerals that were carried to the sites of deposition by streams, wind, glaciers, and marine currents. The sediments of chemical sedimentary rocks are soluble material produced largely by chemical weathering and are precipitated by inorganic or organic processes. Classification of sedimentary rocks The main criterion for subdividing the clastic group is particle size, and the main basis for subdividing the chemical group is mineral composition. The texture of sedimentary rocks is described either as clastic or nonclastic. A clastic texture displays discrete fragments that are cemented and compacted together. A nonclastic texture displays a pattern of interlocking crystals. Relative abundance The principal types of sedimentary rocks are shale (46% of the total), sandstone (32%), and limestone (22%). Clastic sedimentary rocks The sediments of clastic rocks are chiefly clay minerals and quartz. The main criterion for subdividing the clastic group is particle size. In order of increasing particle size, common clastic sedimentary rocks are shale, sandstone, and conglomerate or breccia. Shale: composed of fine grained silt and clay. A prominent feature of a shale is closely spaced bedding planes along which the rock will break (called "fissility"). Sandstone: sand-sized grains predominate. Because of the durability of quartz, quartz sandstones are very common. They are highly permeable (able to transmit fluids) making them good reservoir rocks for water, petroleum, and nature gas. This can also a problem for tunnels below the underground water table. Conglomerate and Breccia: composed of consolidated deposits of gravel (fragments larger than 2 mm in diameter). A conglomerate contains rounded grains; a breccia contains angular grains. Chemical sedimentary rocks The main basis for subdividing the chemical group is mineral composition. Nonclastic rocks are formed from chemical precipitation and from biological activity. limestone: composed mostly of calcite (CaCO3), the most abundant chemical sedimentary rocks, originates by both chemical and biological processes.. rock salt: composed of halite (NaCl), formed by evaporation (evaporites). Rock gypsum (CaSO4.2H2O) is also an evaporite. Gypsum is the basic ingredient of plaster of Paris and is most extensively used in the construction industry for interior plaster. limestone: composed mostly of calcite (CaCO3), the most abundant chemical sedimentary rocks. Chemical precipitation: A considerable amount of calcium carbonate is known to precipitate directly in open warm ocean and quiet water. Organic activity: In their life processes, many plants extract calcium carbonate from water, and invertebrate animals use it to construct their shells or hard parts. Corals are one important example of organisms that are capable of creating large quantities of marine limestone. The simple invertebrate animals secrete calcite-rich skeletons to create massive reefs, such as the best-known Great-Barrier Reef in Australia. The Great Barrier Reef, Australia (a) (b) Shells of calcite produced by corals form limestone. (b) A limestone quarry face in Vermont. The thin layers are lime mud; the white mounds are relicts of small reefs. (c)The fossiliferous limestone consists of small fossil shells. (c) W. W. Norton Features of sedimentary rocks Sedimentary rocks commonly show layering and other features that form as sediment is transported. These features provide key information about the environment in which they were formed. Stratification (bedding): is the most prominent feature of sedimentary rocks. Bedding provides extreme differences in directional properties (anisotropy) in strength, permeability, electrical conductivity, and seismic velocity,which have engineering importance. Principle of original horizontal bedding: bedding planes for most sedimentary rocks were originally oriented in essentially horizontally. (a) (b) (c) (d) Bedding forms as a result of changes in the environment. (a) During a normal river flow, a layer of silt is deposited. (b) During flood, turbulent water brings in a layer of sand and gravel. Stratigraphic formations (a sequence of beds) of the Grand Canyon. (S. Marshak) cross-bedding: under some environment, sediments do not accumulate as horizontal layers, such as sand dunes, river deltas, and some stream channels. Cross beds formed on the leeward side of a sand dune (top) and on the downstream side of river-deposited sediment (middle). (W.W. Norton) Formation of Cross Beds When blowing sand builds into sand dunes in a desert, the sand tumbles up the windward side of the dune, and settles in quieter air on the leeward side. This animation shows how cross beds develop during the deposition of sediment. [by Stephen Marshak] Play Animation Windows version >> Play Animation Macintosh version >> graded beds: sedimentary layers change gradually from coarse at the bottom to fine at the top, often associated with turbidity (muddy) current sweeping down steep slopes in an ocean or large lake. Other sedimentary features: ripple marks: small waves of sand developed on the surface of a sediment layer by shallow water waves or winds. mud cracks: indicate that the sediment was alternately wet and dry, found in shallow lakes and desert basins. Ripples (such as left) can be preserved (right, a layer of quartzite that’s over 800 million years old). Mud cracks (left) can be preserved (right, mudstone of 280 million years old, viewed in cross-section). (S. Marshak) Engineering considerations of sedimnetary rocks Bedding planes are zones of weakness in sedimentary rock masses and may fail if parallel to downslope. For tunneling and underground mining, limestones and evaporites present problems because they are soluble in flowing groundwater, creating cavities. Alkali-silica reation: Silica in certain minerals/rocks react with alkalis (Na2O, K2O) in cement paste, causing expansions and creating map (pattern) cracking in concrete. Constituents that react with alkalis include opal and chalcedony (hydrated fine crystalline silica) and chert (as nodules in sedimentary rocks) and volcanic glass.